It all started before I was born when my father was racing cars for the MG factory during the late 1940s. He had a highly modified and tuned MG-TD, which had been sorted by an Italian mechanic called Pennante who had actually machined engines for Enzo Ferrari. My father sponsored Pennante’s entrance into Canada after the war, and Pennante did his part by turning my father’s car into one of the fastest in the under 1,500cc category. “He polished the inlet ports until they shone like a mirror.”

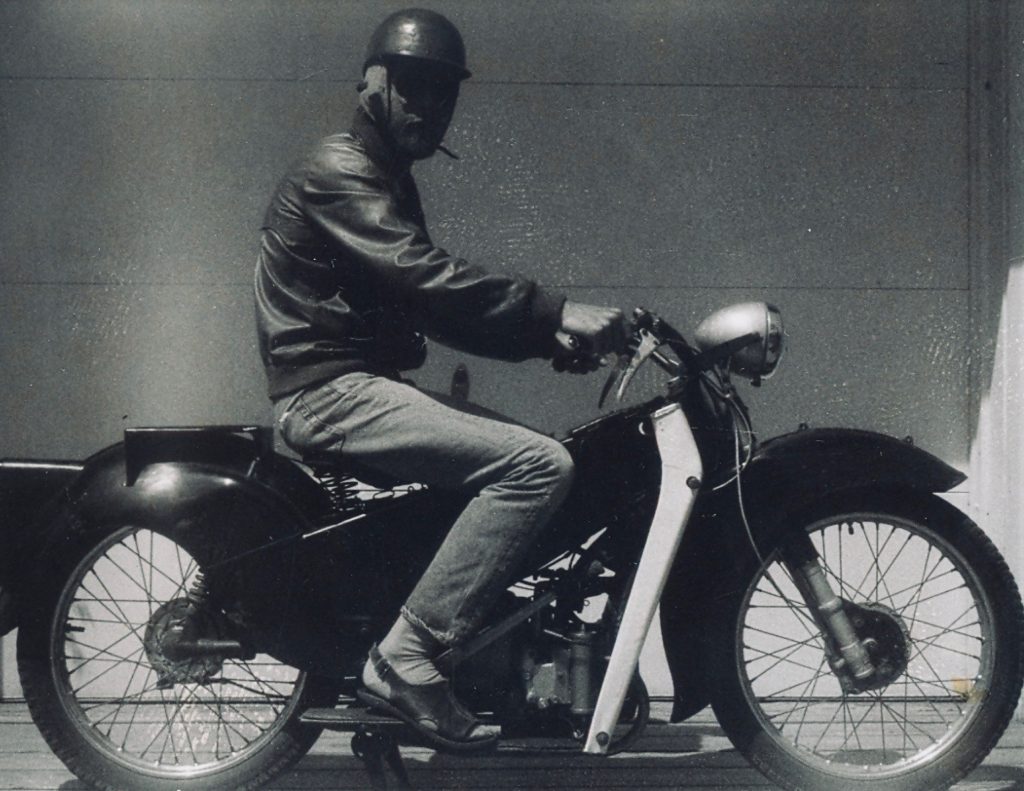

Pennante and Marshall after a win in the rain. I like that my dad has Pennante holding the cup. I know from my past that he always orchestrated photos so he would look his best, and he succeeded.

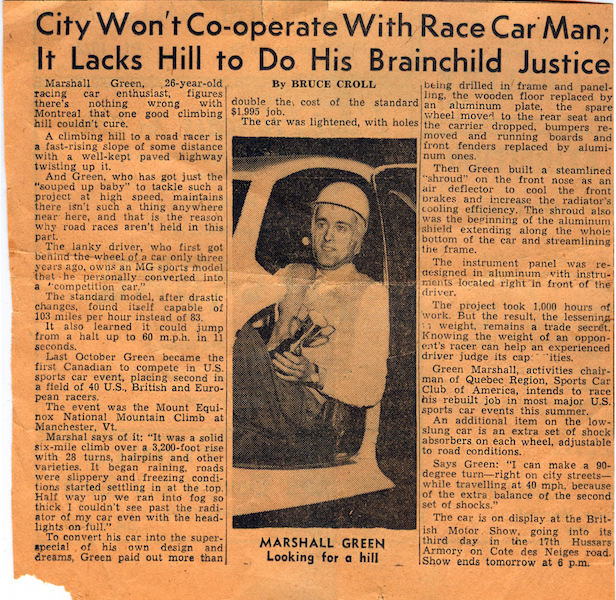

And all was well until a hill climb race at Mount Equinox in Vermont. I still have photos from that rainy dark day in 1951, and I found an online magazine article verifying my father’s story—all of his stories, it has turned out, were not necessarily true.

The “Climb to the Clouds” article reads: “The most outstanding performance was put in by Max Hoffman, driving a Porsche. Max took the 1½ Ltr. Convertible to the finish line in 4 minutes and 38 seconds, 18 ½ seconds faster than the MG-TD driven by Marshall Green.”

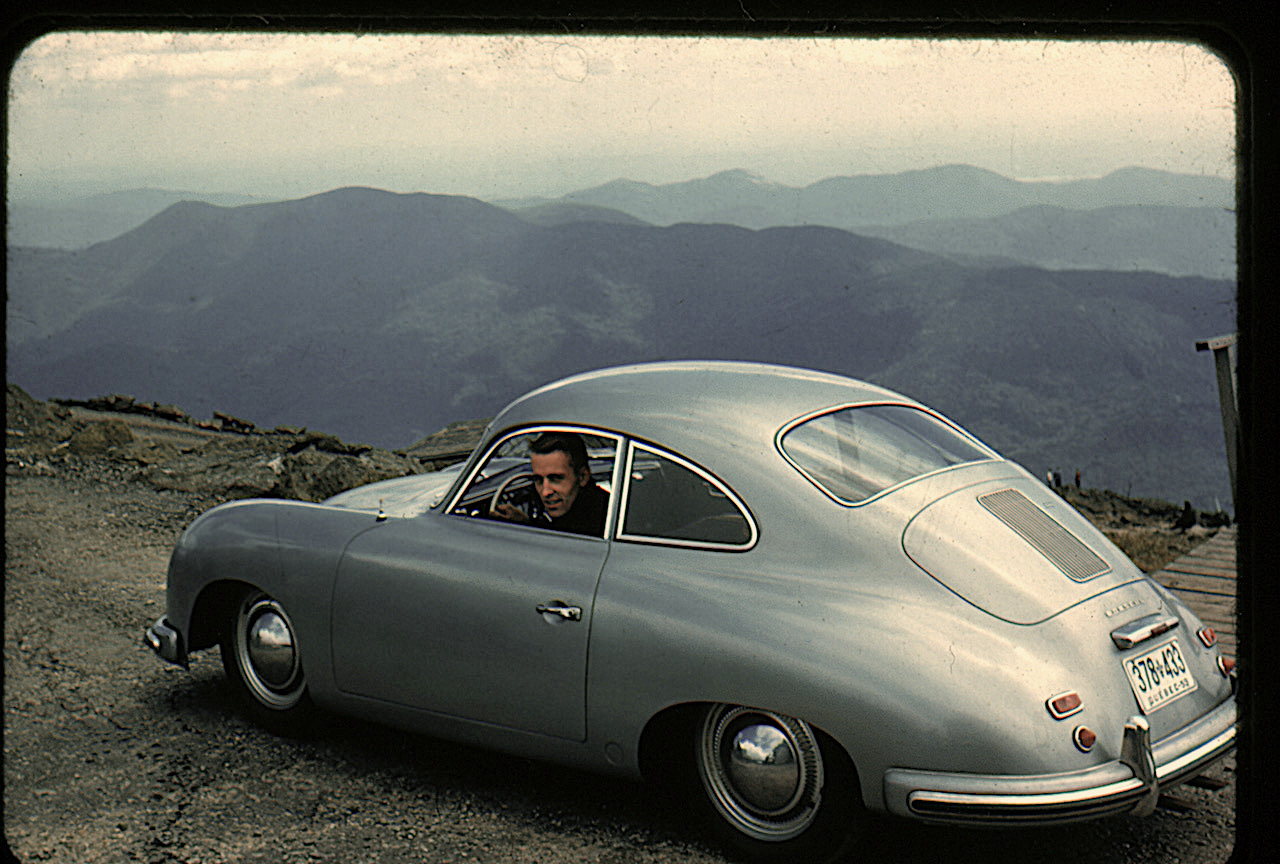

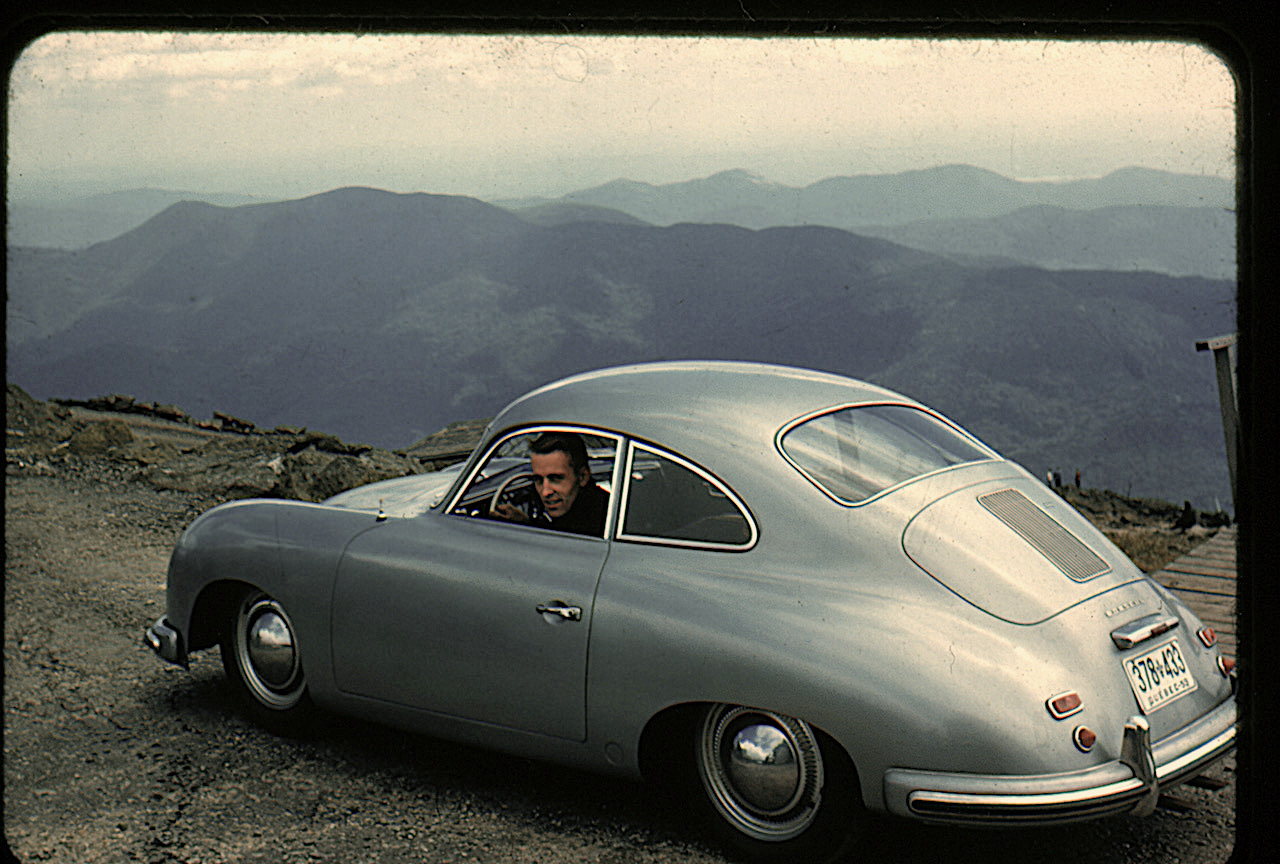

This really irked my dad. As he explained it, “Hoffmann was this middle-aged fat guy in a fur coat with a nose like an anteater who couldn’t drive worth a tinker’s dam. I knew the car must be vastly superior.” And being my dad, and getting advice from his friend Briggs Cunningham who also was not enamored with Hoffmann after having bought a 356 from him in 1951, my dad contacted Ferry Porsche in Germany. And the Porsche factory built him a specially prepared racer that turned out to be faster than even a Jaguar in a ¼ mile drag. It was the first 356 GT car, having aluminum doors, hood, and trunk lid; was sprayed “silver-blue graw” (actually fish-silver grey /505, but my dad must not have liked the name) metallic; fitted with royal blue corduroy and gray leather seats, and had a 1,500 racing engine with a unique one-off camshaft. But it had one major flaw.

“It was simply too beautiful to race. I couldn’t do it. The idea of denting such a machine was unthinkable.” My father loving good machines much more than people. He never really understood people at all since unlike a good machine they did not always give you back the care and love you put into them.

My father in the gorgeous coupe at the top of Mount Equinox, as if to say, I’m king of the mountain now, the photographer probably having had a stopwatch and timing the run up. And he never liked Hoffman or his idea of a Porsche—the Speedster, which, of course, has become the most valuable and coveted of all 356s.

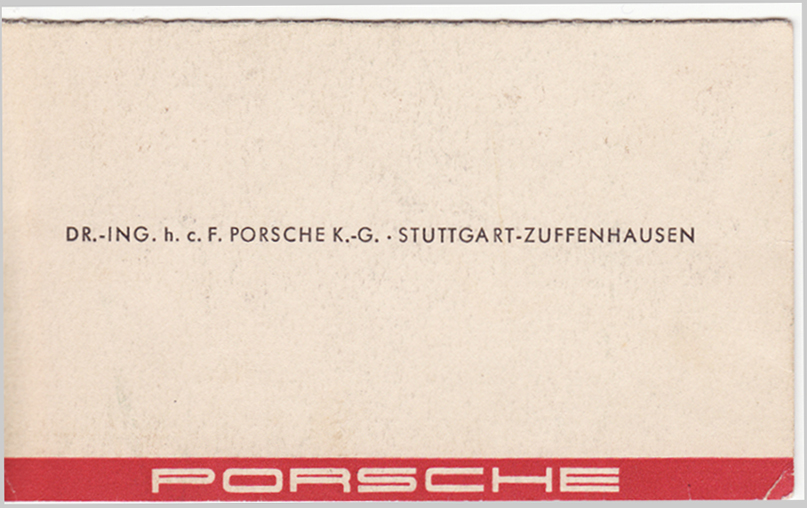

As an aside, Porsche also offered my father the dealership for Canada, but when he tried to raise the needed money, the German millionaire he approached nicked the soon-to-be-prized dealership away from him. I have one remaining copy of the business card my dad must have had printed, a sad reminder of a failed dream.*

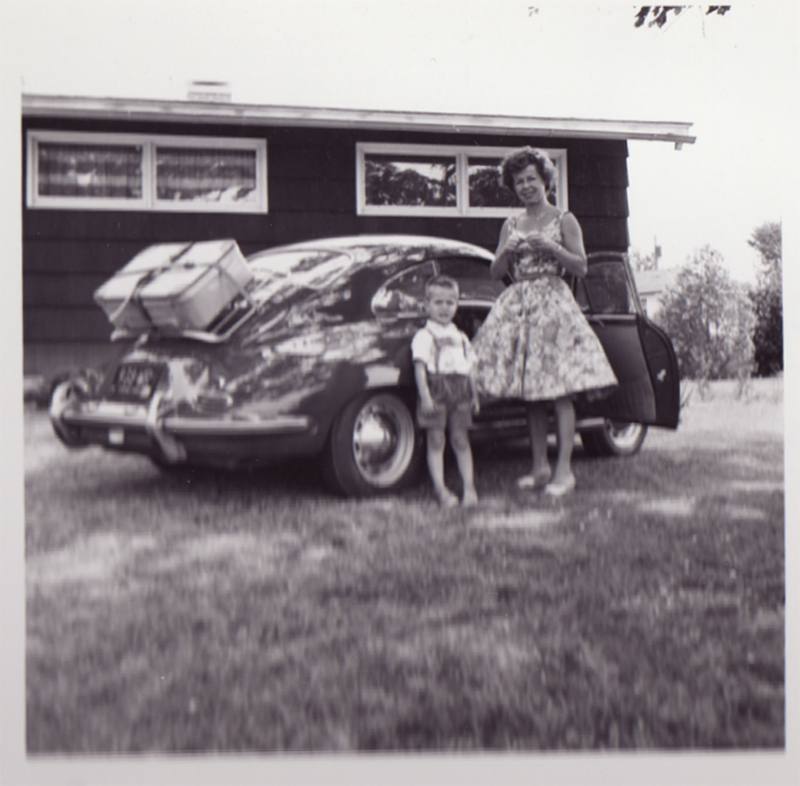

The car was eventually painted black, Dad insisting it was 17 coats of hand-rubbed lacquer specially formulated by a friend, but some years later when the riveted timing gear stripped off the camshaft, he learned there weren’t any of the needed replaceable parts for his unique engine, and was talked out of ownership by trading for a new VW bug. “I had a kid and a wife to take care of.” Apparently the beautiful coupe eventually ended up in northern Quebec as an ice racer. If only I could find the grave.

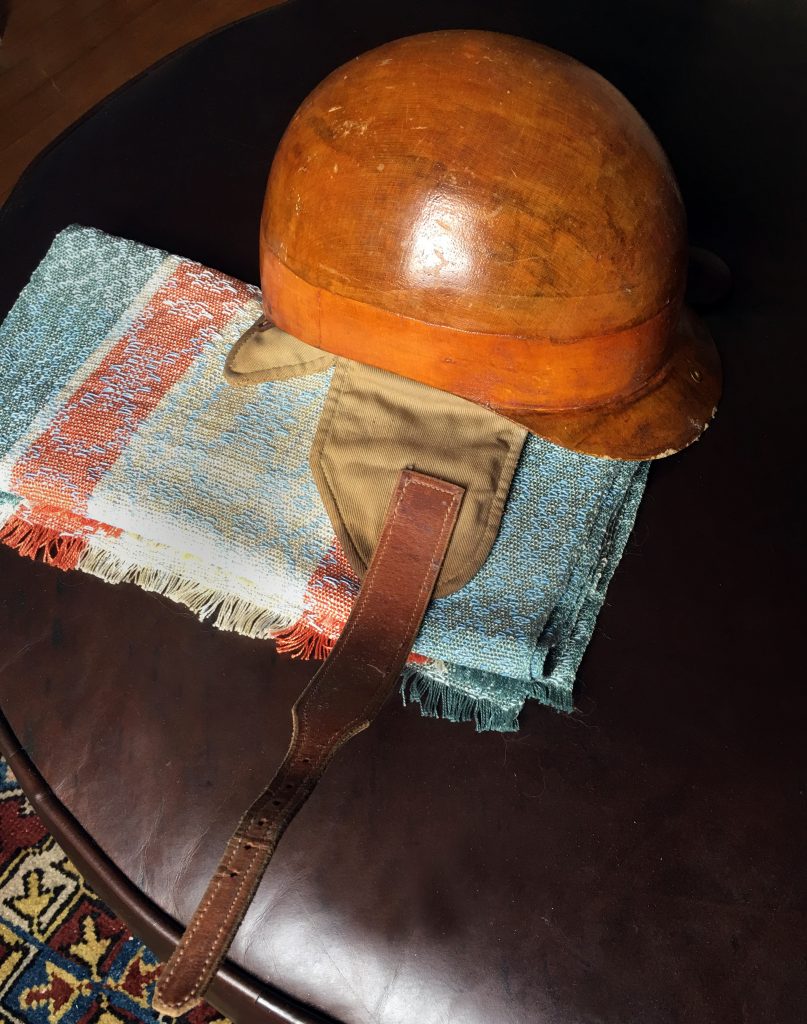

My father’s Herbert and Johnson (Hats for the King of England) helmet. It is the only helmet I ever wore on my motorbikes: BMW R90S and Ducati 900 CR. Helpful in a crash? No. But 30 years at silly speeds, so lucky!

His next Porsche was a 1961 356B, picked up at the factory in Zuffenhaussen. I was about five and still remember the frightening banging of body panels at the Reutter factory. I much preferred the quiet of the upholstery area and engine assembly plant. When it was time for my father to exit in his new 356, the keys were presented by Ferry Porsche himself. A number of white-jacketed mechanics were standing about watching, arms crossed, the fjord green coupe immaculate.

Ferry said, “Mr. Green, we certainly do not need to explain the operation of a Porsche to you!” And everyone smiled brightly. I don’t think my father expected all the fanfare, though who knew what racing stories he’d been telling. Then again, he had been the first buyer of a Porsche in Canada, about the ninth one on our continent.

And my father nervously and mistakenly put the car in reverse and nearly downed two mechanics.

That was the car I grew up with until the day my mother careened into a school bus.

The repaired 356 lost all appeal for my father, who only loved perfect original examples, and he eventually sold it with difficulty. No one wanted it. Porsches were not popular cars during the 1960s and kids always made fun of me because my family drove one, surprising to think of now.

Fast forward to 1973. I’m 16 years old, and although I haven’t finished high school, I’ve been accepted at the Rhode Island School of Design. My father has forked over the year’s $5,200 tuition with a caveat, “This is the last money I will ever give you. Use it wisely!” I can tell this expense is weighty—my family never had any money, the fancy cars soaking up any residuals—and I take my father’s admonition very seriously.

After a week at the school, the only art I’ve done is making a large Styrofoam egg after paying ten dollars out of pocket for the sheets of Styrofoam. I find out it will be two years before I’m allowed to touch a paint brush, so I speak to admissions and ask them if I leave, will my father receive a refund? I explain that I’ve been painting seriously for years and selling work for $200 to $800 dollars—I don’t need to be making Styrofoam eggs to learn about form. (Remember gasoline was 50 cents and a diner meal under $2.)

Admissions is annoyed and wants to see my portfolio and the painting I’ve brought to the college. Big meeting with the Dean and head of the art department—the college offers me a full four-year scholarship to stay. I still want my question answered about the refund.

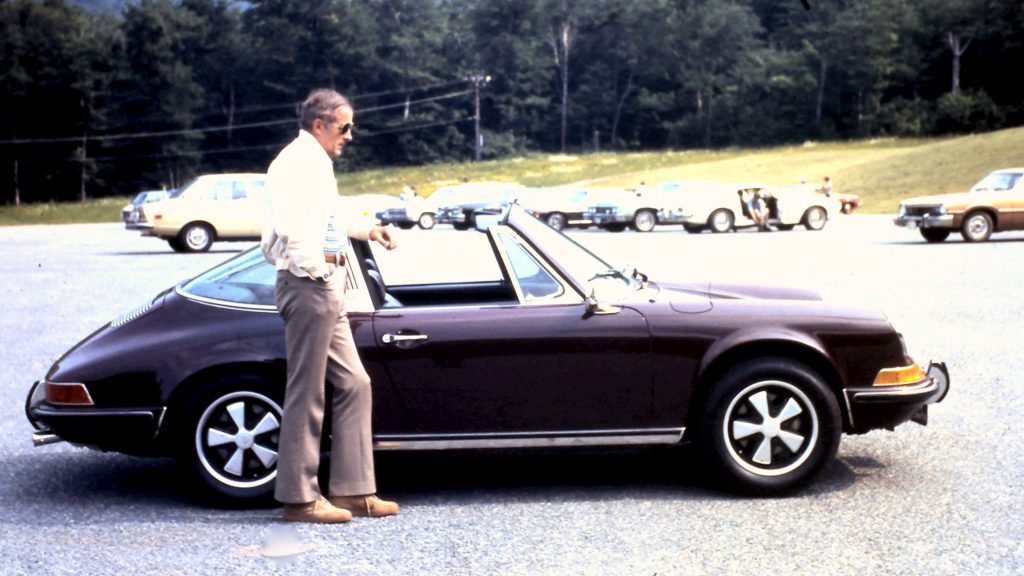

About a year later, my father locates a dream, uses the refunded money, plus borrows all I have—$1,500 from painting sales—and buys himself a virtually new 1970 911 Porsche Targa for bizarrely, exactly $6,700. We drive it from New Hampshire to the Midwest through northern Canada, both shocked and delighted by how fast and wonderful the car is, and my father seems pretty happy, which is a fine reward for his having quit drinking six months earlier after thirty years of heavy alcoholism.

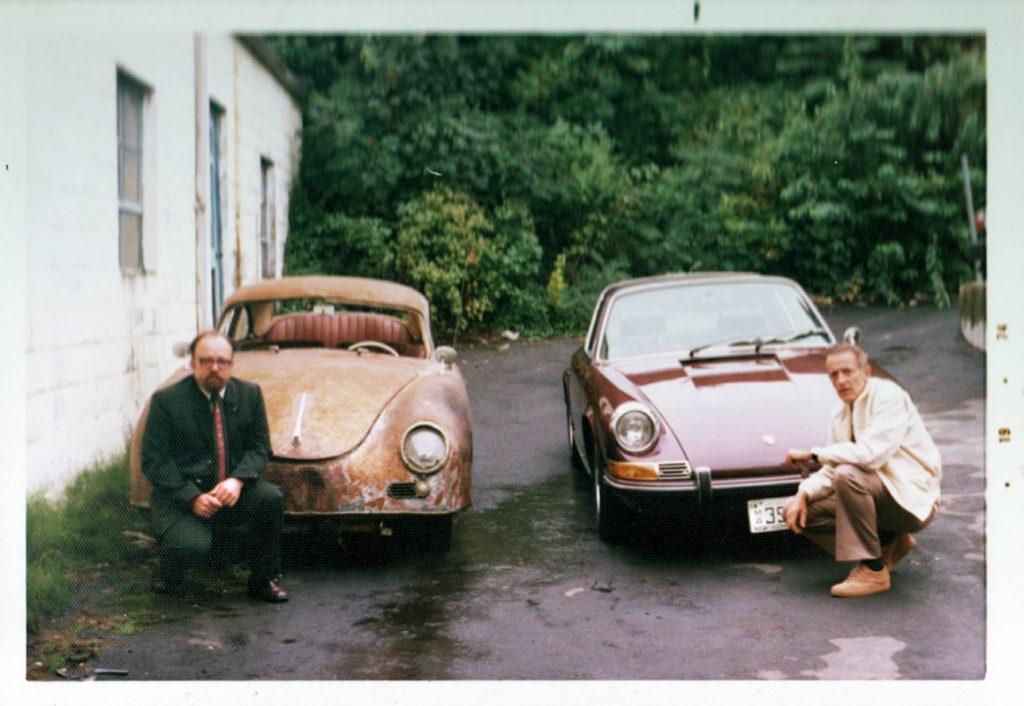

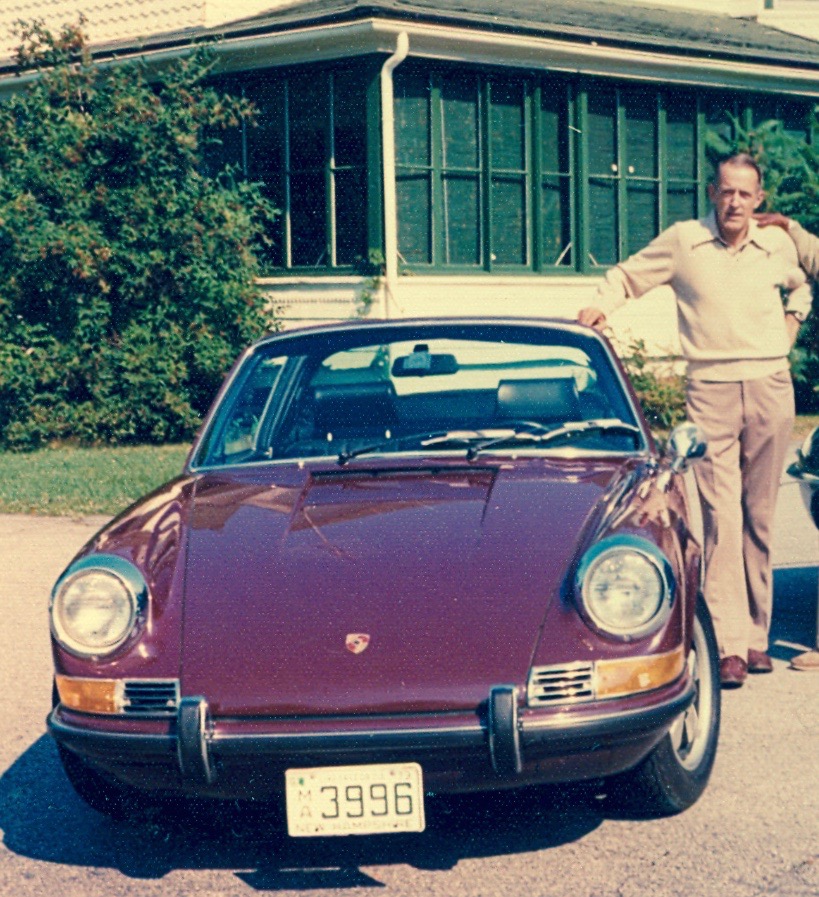

My dad at the Gorham New Hampshire house the day in 1974 when we were about to drive the 911 across Canada, cruising for hours at near 100 mph. That’s my hand on my father’s shoulder, complete with Italian leather driving glove, my father kind enough to allow me to drive half the time. I removed the rest of me from the photograph because I looked simply too goofy, particularly compared to my dad. (Never understood why Porsche placed the windshield wipers in front of the driver.)

About a week later, I leave to ride freights across the country as a hobo, and when it gets too cold in the Rockies, I end up living above a poolroom with jazz musicians in Providence, R.I. I’m broke, actually close to starving, and beg my dad over a payphone to return my $1,500. He mumbles something and I continue hungry.

On one of my prowls through the many colleges, looking for women or food, I see a handwritten index card: “For Sale, 1956 356A 1600S Porsche $1,400,” and I decide impulsively, illogically, that I must buy that car. It seems predestined although I have no idea why—build date and birth date coincidental? I negotiate sternly with the home front—involving my mother—and finally, just a week after I turn 18, I’m headed by bus to Westerly, R.I. clutching the roll of bills in my jacket pocket since I’ve never touched so much cash before. I’ve already spent a bit on a calabash pipe that I’d been eyeing in an old tobacco shop. I’ll smoke that soon enough.

Knowing little about checking an automobile for condition, I trust the seller, hand over the full amount without negotiating, and in the gathering December dusk, point toward Providence. An Alfa Romeo shoots past me. I downshift to third, stomp the accelerator, and repass at 95 miles an hour. Although no one heard it, that shout of excitement and pure joy must linger in the air somehow.

Within an hour I am motoring past the Ocean Theater and the Greek diner heading to my family for Christmas, heading for the Midwest, approaching one of the coldest drives of my life—26 hours, blizzards in western Mass, ten below zero in Cleveland, lost in Chicago, almost comatose by Wisconsin. It was just as cold inside the car because the heat exchangers had huge rust holes in them, dispelling any warm air that might have reached me from the air-cooled engine.

But what an epic delight that drive was! The first of many. I had my own Porsche and I loved it—the ivory dashboard, the red padded cover, the black leather seats, the sound of the racing pipe called a Bursch Extractor. I had earned the car with my artwork, which seemed even more satisfying. That my father told me it was pretty much a piece of junk only slightly rankled, although I realized soon enough he was at least half correct.

But people see things so differently.

One of the jazz musicians from Providence, Philip, was a bass player who had been friends with Charlie Haden during his junkie years. He told me later that my exit in the Porsche was one of the most stunning things he’d ever encountered. We had talked a lot over the past two months, drinking 15-cent Pickwick drafts together in a dive bar, the floor covered in sawdust, no stools, whores shooting in and out to scream at someone. The loft we slept in had no bathroom, I slept on the floor in an old black raincoat, the jukebox in the poolroom below thumping through the floor—we knew the baseline of “Rock Me Baby” by heart. We lived on 25-cent soup and stale bread at the generous Greek’s diner across the street, perhaps named the Town Chef at the time. I had been making drawings of street views every day in a big notebook that disappeared somewhere during the next year. Eventually I didn’t have enough money to hustle pool with, which had previously supplied at least some sporadic income. Betting on credit is hugely frowned upon in rough poolrooms.

“And then,” he said, “suddenly you show up in the most beautiful car I’ve ever seen and quickly load your hobo rucksack, wave good-bye, and roar down the avenue in a flash of silver-blue, that exhaust note reverberating against the buildings even when you were out of sight. Man, that really got to me for some weeks. I couldn’t get over it.”

*My father lost the dealership when he attempted to borrow the huge amount of money he needed. The millionaire he approached stole it from him. This same family (Stinnis?) hired my mother as a servant and therefore they met—my parents. The son attempted to rape my mom, then planted jewelry in her room so that she would be fired when she attempted to reveal his actions. This man later won Canada’s highest award for humanitarianism. Nice, eh? I begged my mother to write a letter to be published across Canada and the United States to unmask this scoundrel, but my mother refused no matter how I begged.

I painted this at 14 years old for my father. Notice that the driver is turning out of the corner because he is utilizing a 4-wheel drift. But I made an error—the front wheels would not be kicking up that much dirt since the car would’ve been rear-wheel drive. But I was a kid.