Mrs. V and Kristan brought me out onto the road that morning, July 1980. My pack seemed as light as my mood was high after a delightful few days at the Verbrick’s—those perfect breakfasts (best of my life), drinking gin and tonic, drinking Special Export (one of my favorite ever beers), playing croquet and badminton, attending the old Neenah theater from my high school days with the miraculous wall insets of miniature dioramas themed on paper making, swimming in the algae green water of Lake Winnebago, that languid relaxed summer pace that we all crave and remember with such joy.

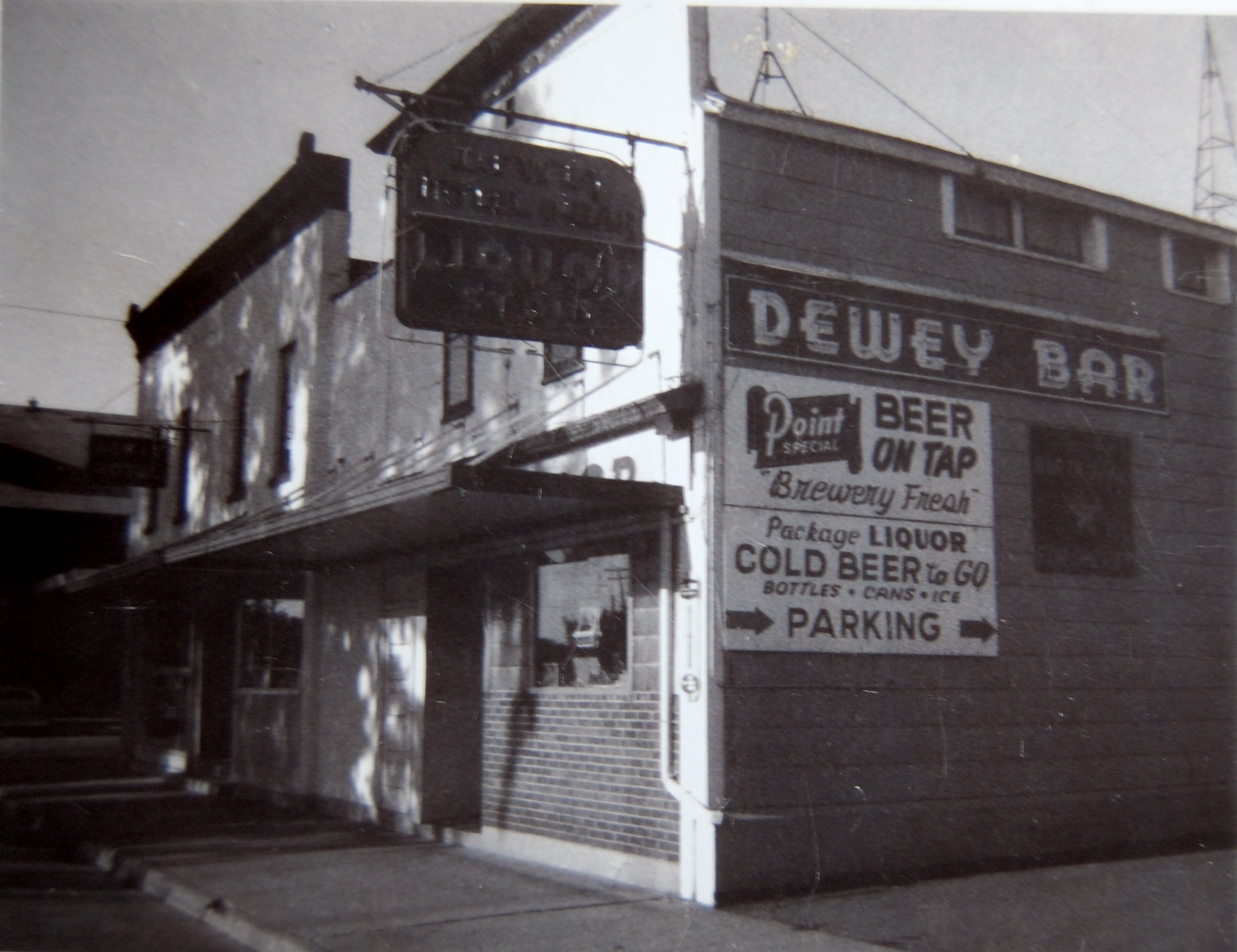

I hitchhiked to Stephen’s Point and found the freight yard by afternoon, some tired diesels shunting boxcars, an ancient brick roundhouse. Talked to a couple brakemen who told me the next westbound was not until 10 that evening. Noticed the Dewey Hotel and Bar, which was just off the tracks. This turned out to be my favorite bar of all time, a true trackside workingman’s bar with schoops (huge stemmed goblet) of ice-cold fresh Point (brewed in town), peanuts in shell poured on bartop scooped from a wooden barrel with an empty can, crushed shells covering the floor. It was also part liquor store, and I was bought a shot of Rich and Rare which was a whisky Hal and I had drank at one time, probably because it was amazingly cheap and still reasonably palatable.

Two Polaroids taken of Dewey’s since I went back many times through the 1980s. The above was probably in 1984. The bar is long gone. Hurts!

I stumbled out of the Dewey into the evening light, ate a Maine sardine sandwich by an aged rusted steam locomotive, and then just lay back on the burnt grass and weeds of an empty lot, the sounds of the freightyard close by, the pink sky swirling above me, as happy a moment as I’ve ever experienced. As the sun settled, I hit a more popular bar toward town to hustle a bit of pool before my trip and added another $25 to my stash. Around 9 p.m. I found myself a woodfloor boxcar on the freight train, which had now been made up and was awaiting its 10 p.m. greenboard. Suddenly a violent wind started blowing sand past the doors, lightning began exploding, trees bending madly in the gusts, and then a rain laced with dirt arrived that shot almost vertical obscuring everything. I was glad to be in my temporary home. As the train rumbled out of the yard, I spotted Dewey’s, the neon sign reflected in the wet street. I called out in delight at the pure beauty of what a moment can be!

ONE DAY

Can a Nuts . . 30

Beer . . . . . . . 25

Schoop . . . . . 35

Shot . . . . . . . 65

Let me speak of the past:

Let me walk into a freight yard

Into the afternoon summer sun,

Across the sandy heat, the stench of tar,

Of creosote, a tired diesel shunting,

The thistle and the gravel;

Middle of the country—1980

Awaiting a 10 PM call westbound.

Let me walk through the open door,

Under the neon of the Dewey Hotel and Bar

(Last true trackside workingman’s bar),

Let me hoist a schoop of cold Point,

Let the barman pour out a can of peanuts

Scooped from the wooden barrel,

Let me scatter the shells on the floor,

Let me feel the breeze through the door,

Let someone buy me a shot of whiskey

Because my smile is as clean as a shout;

Let me just sit there and drink,

The stacked cases of beer at the back

Almost reaching the ceiling.

Let me wait for the first outbound freight

Of a western run. And then

I will stumble out to the yard

And board a wood-floored empty boxcar

And sit against my pack in the door as a

Thunderstorm arrives across the darkness.

And as the freight rumbles toward the west

I will lean against the side of the doorway

That cool rainy wind against my face

And I will see the red and green neon

Of the Dewey Hotel and Bar sign

Dancing in the wet night street.

Very poor quality as well as oddly distorted B&W photo of a painting done in 1980, acrylic on panel, 32 by 48 inches, Point. [Wish I had a better and color photo because I remember this painting very fondly.]

Next morning, I walked up the seemingly endless rail yards of the Twin Cities, which will always remind me of my first night on the freights in 1974 when I almost quit and turned back. So, six years later, I waited all day by a highway overpass for a freight, there being a nasty bull on the prowl, so I stayed off railroad property where he couldn’t touch me, the brakemen in agreement to signal when my train would continue west, and they would also hold up the track number. Once the train would begin to move, I would sprint and leap into a boxcar, a technique I perfected and practiced in Neenah as a 15 year old. Not the preferred safe method, but hobos must be adaptable or they need to become librarians or accountants. Freight trains don’t just halt in cities and then continue like passenger trains. They are broken up and reformed constantly depending which cargo goes to what location. This can take hours or days.

That day was really hot and humid, and I just sat drinking Grain Belt, only purchasing one or two at a time so they would be as cold as possible, the old Hal Stowell trick that I learned in 1972 when we drove together to P.E.I., Hal stopping for singles, over and over, I nervous (not drinking beer yet because of my father’s terrible alcoholism) about Hal getting too drunk, which at that time he didn’t do. Besides, Hal might be the slowest driver who has ever lived, 45 mph on an Interstate being pretty reckless.

This from my good friend Lee Turner, who (among other skills) is the finest weatherer of O-scale steam engines and cars in the world: “Railroad yards are generally of two types, a flat yard and a hump yard. A flat yard as the name implies is flat and the cars are pushed and pulled into the proper tracks. A hump yard is so named because when a train arrives, the locomotives and caboose (back in the day) were removed and a strong locomotive would push the entire train over a hill, the “hump.” At the apex the cars are uncoupled singly or in small groups while rolling at slow speed. As they crest the hump they gain speed and roll down into a broad fan of switches called the bowl, which sort the cars by destination into the appropriate tracks. Originally the railroad used Hump Riders, men who would scramble up the moving cars and control the speed with the handbrakes. This was extremely dangerous so the railroads developed the retarder, a device that clamped against the wheels of the rolling cars to slow them to the proper speed so that they would make it into the assigned track but not collide heavily with the cars already in that track. There would be towers in the bowl with men to control the direction of the switches and to control the speeds of the cars by the retarders. The men controlling the retarders had a list of all the cars coming over the hump in order and with the weight for each single or group of cars to allow them to use the correct clamping force needed.” Just the best! Thanks, Lee.

I watched as train after train was humped, the cars coasting silently to their track position like ghosts in that debilitating heat. The Midwest has these days, perhaps the South does as well— just stagnant, hot, humid, awful. The highway above me churning with constant trucks, banging as they hit the overpass compression gaps. I kept worrying I might miss my train as I ran for another cold beer, the package store way too far, especially in the heat, but who can drink warm beer, and who can stand heat without beer? It wasn’t as if I could lug a cooler trying to race down a freight train. My pack was plenty. Finally, in the relative cool of evening, I caught the train, being forced on the run to jump a poor boxcar, but at least it was a box and not a cement car or an auto rack where I would’ve been exposed. One thing I know, freight trains don’t suddenly stop for any reason because they can’t, so once I was on, the bull was licked.

The box bounced and pitched so fiercely that I had to stand, no way to lie or sit without injury. A bizarre factory out on the plains covered by thousands of small bulbs, spewing horrid black smoke appeared like a Dante vision of Hell. Somehow I did not notice passing the Mississippi River. The warm wet sweet night smell of the great fertile plains came in through the doors as I stood balancing, my legs aching from the constant jolting, holding onto the boxcar door edge, the moon sinking just where the perspective of tracks and train met. I felt that sense of incredible distance that the American Midwest can give, that sense of everything being very close and very far in same instant—a lushness, vastness, middle of my country feeling, Minnesota, that tremendous great moist flat land under a wondrous night sky.

Finally the train slowed a tad and the horrible shaking of the boxcar settled enough so that I could curl up on the metal floor in my wool G.I. blanket and sleep.

I was awakened exhausted at dawn in North Dakota some miles outside Bismarck—as I would learn soon enough—and noticed an upsetting quiet, which is likely why I woke, a moving train always the hobo’s friend. Only when the train stops is there the immediate possibility of danger. Looking out of the door to where other boxcars should’ve been coupled, there was only empty track. “Damn!” I yelled, quickly gathering my gear, jumping down, and running up the gravel, calling over to a brakeman who in a thick German accent explained one track over was the westbound already moving. Scrambling dangerously between the rusty gauntlet of two boxcars I found another open empty and barely managed to leap in at the last possible moment—when a train outpaces your running speed . . . I had almost been set out in the middle of nowhere. Not a pleasant way to begin the day, but at least the random box I’d grabbed was a smooth roller.

My freight rattled past towns with farm machinery sales lots by the tracks, the clear blue sky touched only by high clouds. We rode into the Badlands about noon, maybe later, finding the time only on banks or courthouses as the boxcar passed small towns huddled against the bleak landscape that I loved so much, remembering my drives in the 356. I wrote down names of towns in my journal as we rumbled through having no map.

Bismarck

Fargo

Dickinson

Medora

Sentinel Butte

Beach

Wibaux

Beaver Hill

Glendive

Yellowstone River

Miles City

Big Horn

Custer

Fee

Bull City

Billings

The dirt roads that wound out of the dry pale grass and crazy (to a New Englander) green sage, infinite small tufts, these roads crossing the tracks pale red, the striped hills with blackish tops stood suddenly out on the plains, whole groups and sometimes only these hills but always the sage. I hung in the door, let the wind of the moving freight batter my face, occasionally had a pull of Irish whiskey, that faithful Bushmills, which still [now!] brings back the freights with any sip. The floor of the box was covered with flour and the usual lumber, metal strapping, and so on, but going barefoot, the flour and dirt formed a thick crust on my soles, which later, using a sharp knife to remove, I cut my toes with three scraping sweeps before I saw the blood and felt the pain. Days later a hobo would tell me that I had the dirtiest feet he had ever seen. You will never be dirtier than on a freight train.

The freight kept pounding away; as long as we are moving I’m happy. We reached Montana at Wibaux. Many towns in the West that touch the tracks have grain storage buildings and many times with the name of the town and some farmer co-op name is lettered on the side of the clapboards. These bring a certain but undefinable emotion as I see them rise up in the distance, wavering unattached to the plains like ghosts at first, and then while passing read their faded white letters against the pealing red paint, watch them diminish in the distance again all to the pounding sound of the slowing and then accelerating freight train. I get an unusually clear sense about towns because I pass beside them rather than through as you would when driving. The rail yards are usually on the outskirts of towns and near the poorer section, and this only increases my understanding through this unusual overview.

The freight started snaking along a huge wandering river by early evening. The water was smoothly flowing along when it suddenly began to chop insanely, trees lashing, smaller ones actually flailing the ground. A black sandstorm struck, the sun through the sand a haunting reddish orb. And with the sand came rain. It all passed very quickly and then the settling sun burned slowly very crimson as darkening plains came up to meet it. I sat in the door drinking whiskey, eating oily Maine sardines. On the evening sun that lit the plywood walls of the boxcar with a pencil I wrote:

Bean rode this box and drank fine Irish whiskey and is the baddest bo anywhere. Minnesota – N. Dakota – Montana July 1980

We made it through Billings only to have the air pulled at Laurel. [This is the favorite sentence of all I have ever written, which was taken from my road journal in 1980.] Spent the night frozen in an empty sided boxcar waiting waiting for a westbound to be made up. A lot of waiting in hoboing. Jack rollers were in the yard, and the few other stray hobos were in a panic. [Jack rollers are cruel men from a nearby city who attempt to rob or kill hobos and tramps knowing no one will ever come after them for the crime. They usually have at least one gun and run in packs.]

The huge masts of crime lights gave parts of the massive Dickinson yard ghostly fluorescent sections. I walked to the yard office, entered the hot bright smokey air, filled my canteen, asked about trains heading west, workers staring at me, perhaps at my pure friendly hobo bravado. I stood most of the night in the boxcar, too cold to sleep (and not easy to do with the knowledge of jack rollers a foot) as I listened to the random crashing and banging of couplers, the growl of diesels, then the gunning up to shove freight down the yard—a busy place. Lash-ups occasionally thundered by beside my car, the headlight flashing inside the cold box. I wore my G.I. blanket against the chill, but still shivered, amazed it could be this cold in July. Finally a blueing in the sky, yelling up to an engineer in a diesel, I found my train, waiting again until the bull found me: ”Wanna git off my train?” A nice enough fellow, more a big flashlight guy than a gun guy, just doing his job, not interested in sending me to jail. I walked up the highway beside the tracks, sun just visible now over low hills. When the freight began to roll, I ran and hopped the boxcar right behind the five engines—a mistake!

The day turned warm, sun through the big open doors, and I stripped to a T-shirt. At Livingston, a stop, which you always knew when the air brakes were released with a great out-breath hiss—the mountains now visible in the distance. I walked to a gas station, got a map, looked in a mirror for the first time in days—you tend to age years in the matter of days on the rails, and even with washing, the dirt becomes ingrained. After my first hobo run at 17 years old, it took two back-to-back baths to get clean. I returned to the yard—listening the entire time for the warning horn blow that would signal departure—and began talking to the two hobos who rode the boxcar behind me. Once you have claimed a car, it became yours like a home, and no tramp is allowed to enter it without permission (hobo code). We sipped from our assorted beverages (morning beer for me, Thunderbird fortified wine for the tramps)—July—heading into the western mountains—sunlight in the dust—talking about the road—imagine it!

Freight began moving, and we jumped into our respective boxes. In the mountains I could see the end of the freight and caboose snaking along way below us as we wound higher very slowly through land only the train tracks crossed, nothing else but true wilderness. Three extra diesels were cut into the center of the train for the climb—helper engines. My car was a Santa Fe Aircushion and rode like a Pullman coach, probably my favorite car ever since along with its smooth ride, it had a fairly clean wooden floor. By this time, I had learned to choose my rides carefully when possible, but as I mentioned, I had made one poorly calculated error. At least when at the front of the train there was virtually no hump, which is the slack being pulled out of the couplers. This becomes magnified the further back you are riding, sometimes enough to knock you down if you’re not holding on. I had never rode this far forward before because of fear of detection.

Warm diesel exhaust from the multiple lash-up occasionally gusted down past the doors where I sat, legs dangling, watching deep pine woods fall away behind and beside me. Many people do not understand that the diesel engines only turn an electric generator; the train is actually moved by the rotation of electric motors driving the wheel axles. When the train stopped at the crest of the grade to disconnect the helper engines, I scrambled down the roadbed to wash in an icy clear stream that formed small pools. Nervous at being left behind to be eaten by bears, I filled my canteen quickly.

Okay—The mistake. Did anyone see it coming? I bet Lee Turner did, my expert on all things American railroad. Tunnels! The first tunnel was sudden blackness, an extremely loud grinding growl, hot exhaust covering my face like a giant evil hand attempting to kill me through asphyxiation. For a short second my animal mind reacted that I was actually being murdered, and then an instant later my rational mind figured out what was happening—truly terrifying. Afterwards, I leaned out the door catching the fresh wind, coughing horribly, my eyes burning, reacting to the light with thanks to God the tunnel hadn’t been any longer. In 1985, five years later, I would ride through the longest tunnel in the country, which is west of Denver, Colorado, but I knew not to be just behind five or six poisonous diesel engines.

Some notes from Lee Turner on tunnels: “Yup, tunnels are not a fun place. Under the Detroit river between the US and Canada there’s a railroad tunnel. I was railfanning in the early 1980s and watched a freight coming through. About three minutes before the locomotives came out of the tunnel, black smoke started pouring out of the bore gaining in intensity until the engines popped out almost blowing a smoke ring when they did!

“Imagine what it was like behind big articulated steam locomotives back in the day. With steam engines it was much worse because you had the heat and moisture from the steam as well as the overwhelming coal smoke. That’s why the Southern Pacific turned their Mallets around and invented the cab forwards saving their engine crews who were already at the limits of what was humanly survivable. On approaching a tunnel the engineer and fireman would close up the cab as much as they could, douse their kerchiefs with water, cover their faces with them and lie on the floor until they were out of the tunnel. Many mountain railroads provided gas masks for their engine crews. Other times, crewman lost their lives when the train would stall in the middle of the tunnel and the smoke and steam from restarting the train would suffocate them. The Great Northern route to the Pacific Northwest goes through the Cascade tunnel which is eight miles long, which during the steam era had to be run with electric locomotives pulling the steam locos and cars.” [Thanks again, Lee! So freaking cool to know.]

“I get an unusually clear sense about towns because I pass beside them rather than through as you would when driving. The rail yards are usually on the outskirts of towns and near the poorer section, and this only increases my understanding through this unusual overview.”

Exactly, and that’s how it should be modeled.

Bingo!