Imagine these words becoming worn by the road as if each syllable is bent by the hungry miles and each paragraph twists the binding crooked.

The day before the first day on the road, I brought eight paintings [to become the Forum 8] to Desroches Gallery in Montreal, Canada. Trouble and confusion at the border forced me simply to jump in the Volvo and drive off without any correct papers or authorization, listening for the gun shots—there comes a time when we are no longer willing to go along.

Next day—out on the road, northern Vermont, 1980, the New England July sun, my now-so-familiar leather pack leaning, the triangular form of the highway under foot, the thin clouds following the sound of vehicles passing, my thumb held high.

Leaving Burlington, one of the first memorable rides was in a mint yellow 1957 Chevrolet Belair. It was driven by a cool Long Island guy in shades who looked a bit like Richard Gere. The bizarre thing is, this was Carlo Connors who would three years later come look at my father’s 911 when I was considering selling it after he died; my mother gave the car to me since it was my college money that had purchased the Porsche in the first place. Carlo and I have been friends ever since.

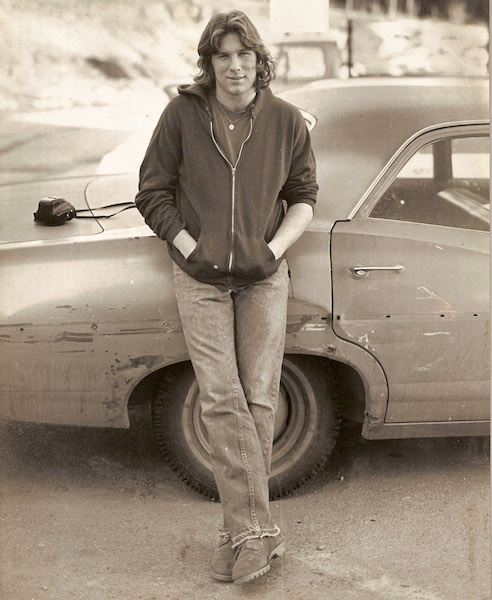

And I could not resist this photo of Carlo’s father Paul, one of the main reasons the world loves the Irish from northern Maine (Millinocket). He was one of the best!

At a crossroads by a gas station and dairy bar in Charlotte, an aged battered Ford driven by a very fat woman picks me up. I squeeze into the backseat crammed between really fat kids with buckets of fried chicken, as an old Mexican in the passenger seat, his face like tree bark, his hands bent knotted strong reaches me back a nearly-empty warm pint of Canadian Club, which I must sip from attempting to hide my disgust. When he finally understands the distance of my intention to reach the West Coast (his English is terrible), he jerks toward me with great joy and mad nodding a freshly opened pint. He has at his feet a paper bag full of these pints, and as I exit, he insists I keep the just opened one with huge unspoken ceremony, which I foolishly keep pulling on as I await my next ride just because I love the man and his indomitable toothless poetry.

In the hot southern Vermont sun, in the overly sweet haze of C.C., images of Club Super Sex in Montreal the night before keep returning—that strange spatial relationship between a dancing naked woman showing (flaunting) her assets and me glued to them. A purely visual experience: the woman being only a body and me only part of a paycheck—though the physical distance is slight, the emotional distance is extreme.

The mechanical condition of the next car is the worst of all my rides ever. It was as if someone were pounding the bottom with a sledge hammer, obviously the U-joint in the driveshaft, which I explain to the driver. “It’ll be fine, man. Been doing that all day.” But after ten more miles, the joint gives. We both sat for a moment, the front seat vibrating in the afternoon sunlight and silence, and the driver seemed little concerned, so I left him with the Mexican’s pint of C.C. and continued walking toward Bennington.

I finally approach Hal Stowell’s at dusk—his place always pivotal of any true road trip during this era—I actually managing to talk my last ride into dropping me right at the driveway, a hitchhiking first considering the many back dirt roads leading to the cabin. At that time, I could usually excite drivers into going way out of their way for me, allowing them to believe they were part of something magical and important. (Buying them beer always helped!) I was always attempting to do this because every moment I was alive seemed like a miracle. Maybe this was from being so very sick and inside most of my childhood?

The next morning Hal dropped me off on Route 2 heading west out of Greenfield. Funny how many good-byes Hal and I have had at the side of a highway. It was so sentimental and tender to watch Hal’s faded-blue early VW bug U-turn and head back east to Wendell, that chugging exhaust note disappearing. He was a wonderful friend and mentor, who I owe so much to for opening my mind to written poetry as well as the poetry of being alive.

I shouldered my pack, looked up at the dark sky. Rain was held in the humid clouds as myriad black flies collected around my head, the strange caterpillar defoliation giving the hills a terrible burnt pink color. Just as the rain began, an old mail van pulled up and I avoided storm. There is always a moment at the beginning of a cross-country road run where you wonder, “Do I really want to do this?” You’re usually hung over, generally tired, bugs bite, no rides, hungry, wicked thirsty and so on. This might be why so few people have hitchhiked for long distances; the real road breaks the weak and uninspired quickly.

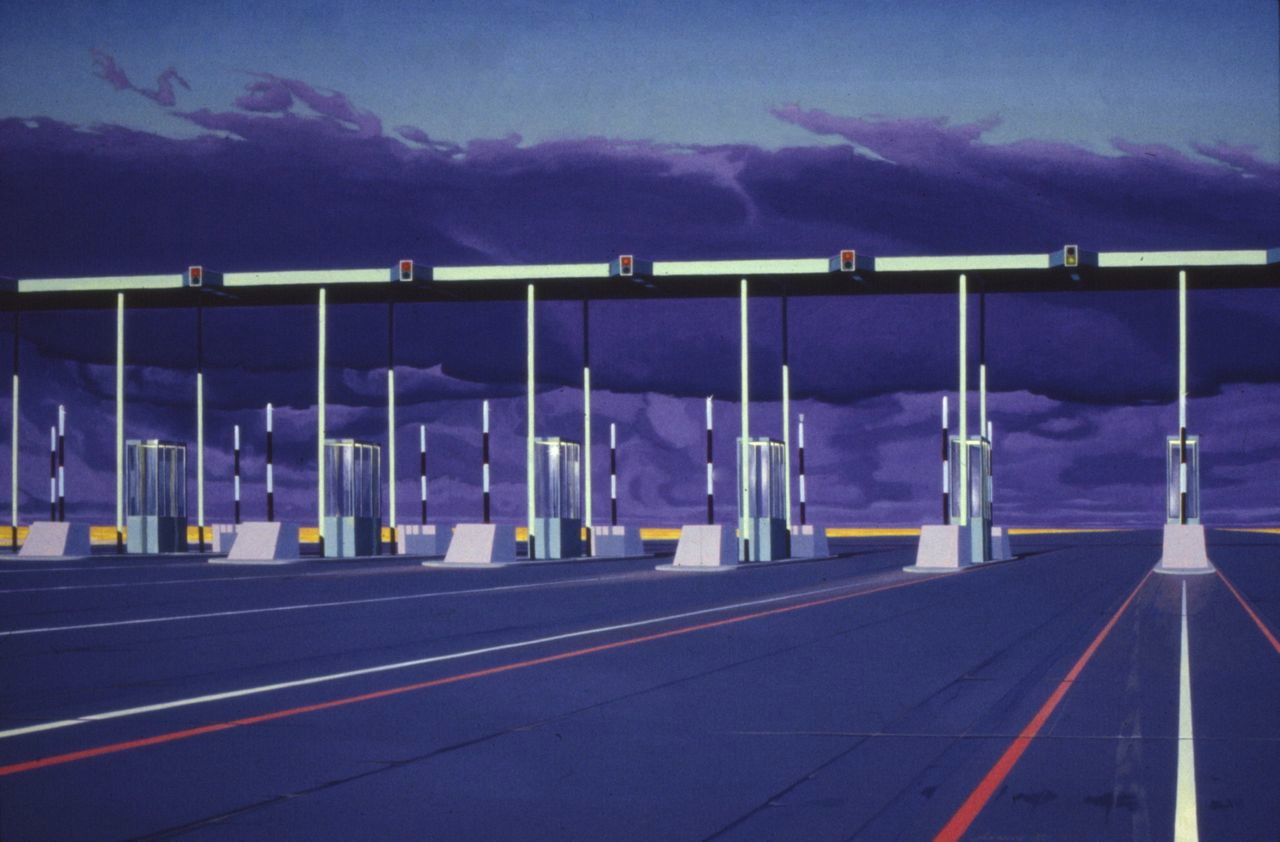

In Albany, I stood at the mouth of the New York State Thruway sipping Bushmills whiskey as a black cloud came off the horizon and drew over, a powerful rain following, the trucks shifting up out of the tolls, all lights now turned on in the storms darkness, last sun raking the booths. I was so overwhelmed by the moment that I painted the memory a year later. I actually had a woman who worked for the state photograph the very same tollbooth for me, but it was so ugly that I invented my own version.

I walked a great long bridge at Niagara Falls at night, down below me the churling river and glowing power houses, the turbines throbbing, the sky a weird orange. On through the night into darker Canada, crossing the border always easy since I’m a Canadian citizen, finally finding Interprovince 401 which is so straight and wide toward the East and Kingstown that I once fell asleep driving a drunk’s car while hitchhhiking (1974 with Kris), waking up doing 80 mph up the grass median. Falling asleep at the wheel one time cures you forever, believe me!

Stranded in London, Ontario at around 3 a.m., I start a drag race in the style of Natalie Wood in Rebel without all the girlish hopping around and handing of dirt. I was simply sitting on a cement berm on the outskirts of town in the middle-of-the-light lull when a souped up Mopar with six guys in it burned rubber a few feet from my feet. I guess they appreciated my cool of not moving because they returned with a hotrod Camaro and I was the signal tree. The six guys won.

In the early morning, a brandnew red Eldorado with white leather interior glides up and then the driver pays for a stop of donuts and coffee. The guy was so excited about his new car he had to share the joy with someone. I slept in a farm field for a couple hours until the dew woke me. Another long walk over the Sarnia Port Huron bridge with its strange feeling of scale because it’s so increbibly large. I remember other hitchhikes when I’d walked the same bridge, never once getting a ride over it.

The Blue Water Bridge which I walked across about half a dozen times.

As a hitchhiker, it can become like watching a series of poorly written TV sitcoms. Each ride is its own bit of drama and humor because people want to talk, tell you their lives, complain about their lovers or kids or drug dealers or bosses. They rant on as they would on a psychiatrist’s couch. This can be okay if it doesn’t go on too long, but since you’re moving forward, which always feels good, you can tune out or pretend to fall asleep. At one point (mid-1970s) I dressed all in white and received rides from people who insisted they had never picked anyone up before. The height of your thumb is critical as it displays attitude, the fact that your luggage is in front of you fully visible, that there is a sensible area for someone to pull over just past where you are standing; sometimes I used a written sign WEST if I wanted to go East. [They stop to tell you you are headed the wrong way.]

Then there are the classic moments that you remember forever and that become stand-alone stories:

Some years ago when hitchhiking west, I was picked up in a cloud of dust by a broken-looking jacked-up Buick pointed north out of Detroit headed up through Pontiac to Flint, Michigan. Now the driver of this rig had a CB and his handle was “The Waterman” and he talked something like this: “Yall dis da Waderman comin’ atcha, yeassur, dis da Waderman, movin’ goood, feelin’ goood; I godcha wader, I godcha juice, I god wadcha need tagit loose.” And the response by the truckers in that area was something like this: “Come agin, good buddy.” They didn’t understand a word. He looks at me: “I’z world-wide, man. Worl-wide!”

Well—I suggested we get some beer. And once it was understood that I’d be paying, the Waterman immediately nosed the Watermobile, or the Black Medallion as he called it, to a package store. I bought us a couple racks of Stroh’s—the fire-brewed beer and a few pouches of beer nuts. Back on route, I snapped one open and proceeded to drink it. The Waterman, however, just went nuts: “Aww, man, whadchu doin’ man. Keep dat ting low, man. Keep dat beer low!” The low sounding like a long moan. Then the Waterman gave me a lesson in Drinking Beer on a Highway. First his head swiveled madly on his neck, his eyes searching insanely—backwards, front, to the sides, above for helicopters—then he slumped way down on the bench seat, impossible now for him to see the road, I ready to grab the wheel, then he yells, “Alright man, gimme da beer. Keep it low!” I slipped him the Stroh’s bumping the thing along the floor mats. Crouching even lower he tipped the beer back and took a swallow. He came up for air then and hopefully to see if the Buick was still on the road and he handed me back the bottle, real low. The fucker was empty! Some sip.

Thus we piloted up the road, I trying to imitate his drinking technique, he muttering crazily every so often on the CB. After our third beer, the Waterman suddenly fought the Buick to a lurching stop in the breakdown lane. He hops out and wrenches up the hood—damn, the Watermobile has died, I figure. I get out my side to assist, being a bit of a mechanic especially on 60s GM. “Right man, right, preten’ you workin’ on da wires, preten’ you workin’ on da motor like.” But the Buick isn’t wounded, the Waterman is just having a pee.

I still use this pee-stop technique today, though I don’t keep my beers quite as low as he did.

These are the gems of rides that you pray for when on the road. I’ve had lovely young women take me home and cook me a huge breakfast—nothing else. Her young husband was in the military. I’ve had lovely young women pick me up with other interests as well. The thing is, you never know what might happen. I’ve turned down only about three rides in 22k miles and correctly so each time. That’s just pure instinct. I’ve even been in a car that was in an accident, which is very strange: “Well, thanks for the lift. Hope you’re okay. Sorry about the car . . . ” as you walk away from the disaster.

After the Waterman reluctantly turned off—beer was gone—I got a ride with a junkie in a van who couldn’t believe I wasn’t holding. “Things been tight. I hear you, man. I dig you, man. Really tight. But you got NOTHING?”

Then the back of an open gravel truck in with a couple wheelbarrows, the wind at 50 mph feeling wonderful over the beer buzz. And then just as suddenly—no rides. Dusk is settling in, bugs are beyond horrendous, I’m in the middle of a Michigan swampland, so I’m forced to hitchhike both directions—a rarity. Finally at dark, a hopped up Nova takes me to a crossroad store and gas station so I can at least get a sandwich. I watch the store close and am left in darkness. Besides some rednecks trying to pelt me with beer cans, not much happens until dawn when the same Nova picks me up again, big lockup of brakes, heading to work in the other direction. “Oh, man, I couldn’t believe it when I saw you still standing there—I had to stop!” It had been a 10-hour wait. My record was 17 hours in Sudbury, Canada in 1973. It’s a gleeful challenge among real road hitchhikers to tell their longest wait, but this wins: “This guy I knew got stuck way up on Canada 17 by a cafe. He couldn’t even get a bus, nothing, just had to keep hiking. He eats at the cafe twice a day, right? Runs out of money, right? Starts washing dishes at the cafe, right? Eventually marries the waitress! Now that, my friends, is the record.” [Told to me in the Sault Ste. Marie bus terminal.]

Near the Ludington ferry dock, I eat at a classic lunch counter, a wonderful dollar breakfast, talk pool with owner Steve and then wait on the beach for a bit until the smell of dead fish is too pungent. A dumpy girl in an ill-fitting bikini keeps eyeing me. It all seems so sad. The boat leaves at evening as heat lightning drums the lake. Trying to find a guaranteed ride exiting from the ferry, I talk with too many people and finally connect with a madman. This guy will not stop talking in his paranoid-hyper way. He’s obsessed with magnet motors, Jesus, North Dakota farmers fighting among themselves, and shifts between subjects mid-sentence. I don’t care. I just don’t want to be marooned all night again. In my exhaustion, I feel as if the country is beginning to come apart, and I wonder now if this was the start of the loss of American, when the wealthy took our country away from us.

Leaving Green Bay, another guy tells me about his wife and kids being murdered, and I feel certain he has killed them. This kind of anxiety is another challenge of the road. You pass through so many lives in a day, it can overwhelm. You don’t eat much, you drink too much (I always had Bushmills in my pack), you rarely sleep except fitfully. All part of it. But I’m in Wisconsin and headed through the night to the Verbrick’s which is a second home to me and where I’m always welcome. Reaching the outskirts of Neenah, I walk the last miles past foundries and across huge farm fields, the flatness amazing, the smell of the wet summer earth amazing, the lightning still cracking, then a fierce pounding downpour, and at dawn the three red blinking radio transmitters that I know so well from my high school years.

I sneak silently and damply into the Verbrick’s house by Lake Winnebago just as the sun breaks the horizon. Curl up in the corner on the living room carpet under the painting I gave Paul and Barbara so long ago, and I sleep. When I wake towards noon, Mrs. V has the signature perfect breakfast ready for me. She has also taken my pack and washed and folded all my clothes. She was the most Christian woman I have ever known, and I loved her like a second mother. I so miss you, Barbara! I’m crying as I write this.

The author with Barbara and Paul Verbrick, Seattle, Washington, 1991, the last time I would see either of them although Barbara and I talked every Christmas until she died. My hat, purchased in Lone Pine, California was brand-new that day and the palomino jacket was still pretty fresh even if purchased in Burlington, Vermont, 1983, but that’s a whole other story.

Chapter One [Excerpt from A Repair Manual for New England Melancholiacs]

1982

On one of those blissfully soft spring afternoons that New Englanders wait for all winter, Neal MacKensie was stopped by a jacket hanging in a shop window, and he stood transfixed, excited, like bubbles rising in water from someone holding his breath for too long. He looked through the glass, unable to move.

It wasn’t an ordinary afternoon for him—frozen parts were thawing and an odd sap seemed to be mixing dangerously with his blood—but then it wasn’t an ordinary jacket either. Although he was certain about the past winter’s arctic cruelty and the emotional damage it had brought him, he had no idea what do about the jacket. So he simply continued to stare, considering, weighing his options.

The negatives aligned first: he couldn’t afford it, he’d never cared much about clothes, and he hadn’t had a drink since Christmas; with a shudder he realized that it wasn’t a jacket you wore sober. But there it waited, magnetically calm, hanging splayed behind the glass, above a sandy rock, next to a half-rotten cactus. An obvious stray, the jacket was the first thing that had dented his depression in months, so he walked into the store.

“Can I help you?” she said, tall in cowboy boots and ponytail.

“That jacket.” He pointed.

“In the window? Isn’t it a beaut?”

“Is it?”

She studied him for a moment, and his uncertainty returned. “Would you like me to get it for you?”

He nodded tentatively. She placed one boot on the edge of the window display and reached with a skinny arm, but when she held the jacket out to him, he couldn’t touch it.

“It’s a forty. Don’t you want to try it on?”

He nodded again. She guided each of his arms into a sleeve, settled it across his shoulders, smoothed it with her palm, and stepped back. “Wow. My God! That really does look amazing on you. You couldn’t ask for a better fit.” She brushed a nervous finger across the bottom of her nose. “It’s like tailor-made.”

It probably looked foolish on him, but he didn’t care—it felt fantastic, like some kind of psychically protective armor. Cut as a western-style sports coat, the electric-yellow leather shined like overly lit skin and was piped along its lapels, pocket flaps, and ostrich yoke with vibrant turquoise cloth. A row of four mother-of-pearl buttons at the sleeves and two in front reminded him of pool-table diamonds. He rubbed his hand across the smooth hide as if it was the first thing he’d touched in months.

“Look in the mirror.” She steered him to his reflection. “Amazing, huh? What did I tell ya.”

He stood there stunned, almost elated. The color alone was overwhelming, reminding him of a Matisse painting—pure joy. “How much?” What was he saying? What was he even doing in this store?

She lifted the tag on the sleeve. “Two ninety-nine.”

He shook his head, reluctantly began to take it off.

She touched him to wait. “Can you put a couple hundred down?”

“A couple hundred?”

She swayed toward his ear and whispered. “I shouldn’t tell you this, but we’ve had it awhile.”

“I want the jacket. Actually, I really need the jacket, but I’m getting on a plane to California in a few hours, and I won’t be back for two weeks. At the moment, all I can do is fifty.”

She sniffed a couple times, the way someone sniffs who’s just done a line. “I guess a Western store in Burlington, Vermont wasn’t the brightest idea. You want a tequila?”

“A tequila? You’re allowed to do that?”

She walked behind the counter. Two shot glasses of amber appeared. She handed him one, downed the other.

He stared at his. After the winter of not drinking, the vapors hit him so fully that he felt it all the way to his core. The abstinence, along with his vow of celibacy, hadn’t been easy. Still, he knew only too well why he’d quit everything. The shot stared back at him with its one tarnished golden eye.

“You’ve got to have that jacket. Can you do a hundred?”

“I shouldn’t do fifty.”

She glanced out the front window. “Okay, seventy-five.”

He threw back the shot.

I’m right there with you!