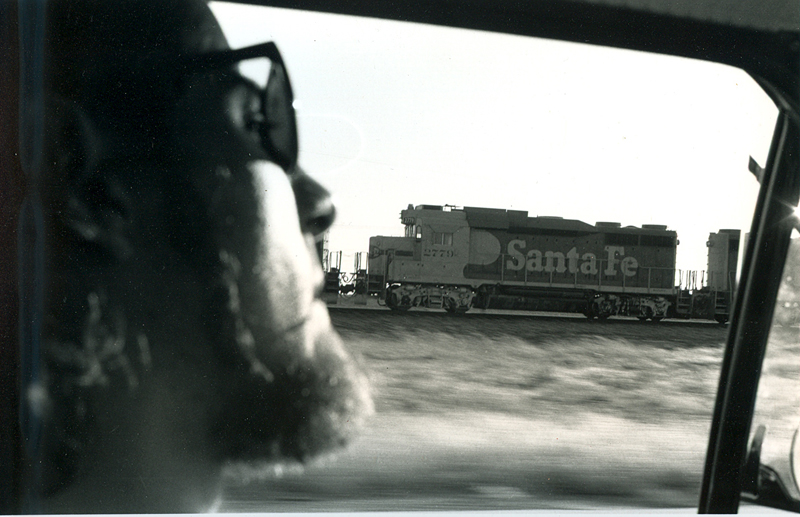

I’ll get back the the 1980 run in a moment; we were just coming out of the deadly tunnels, riding directly behind a poisonous lash-up, but I must tell a story from my first day on the freights in 1974 when I was 17 years old.

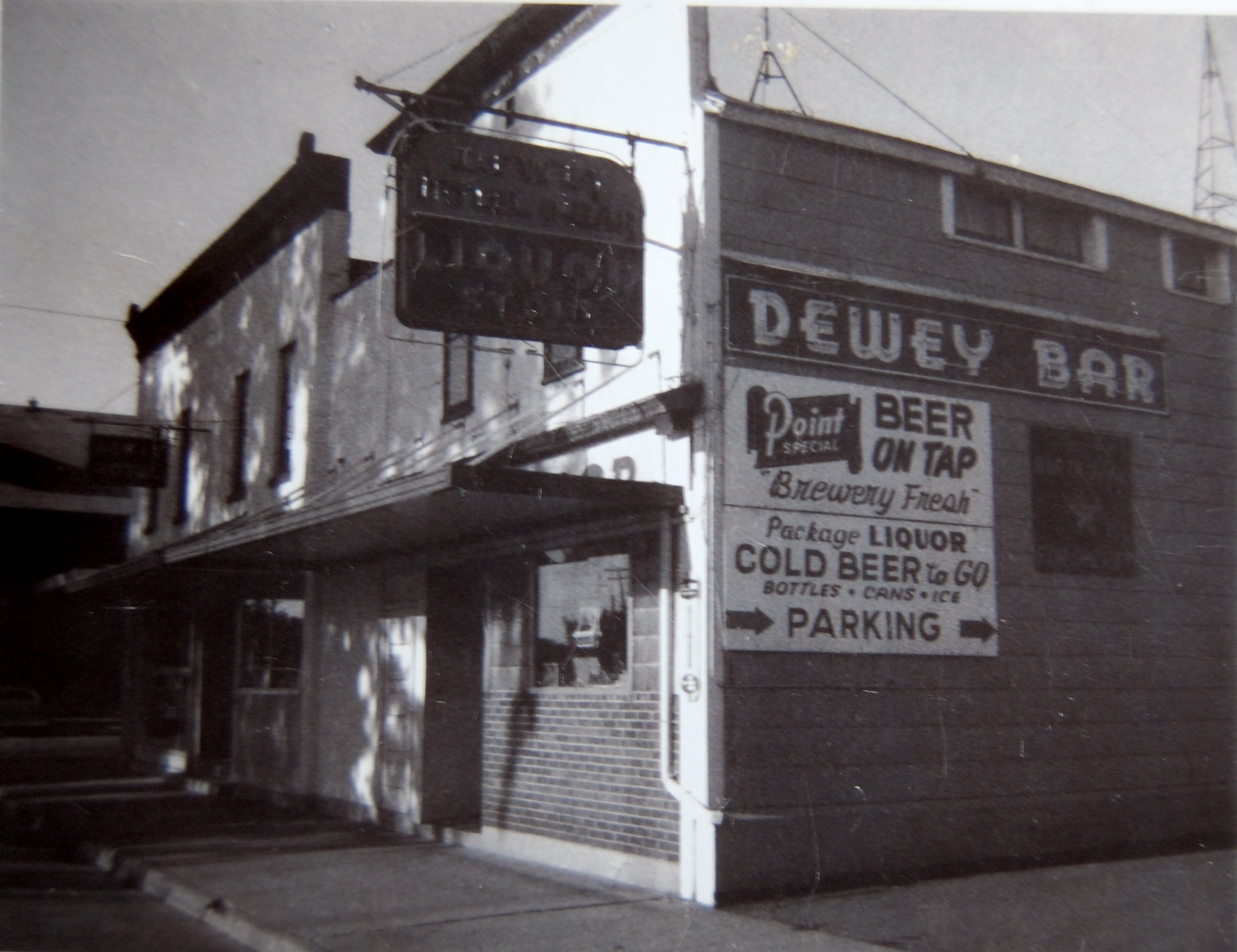

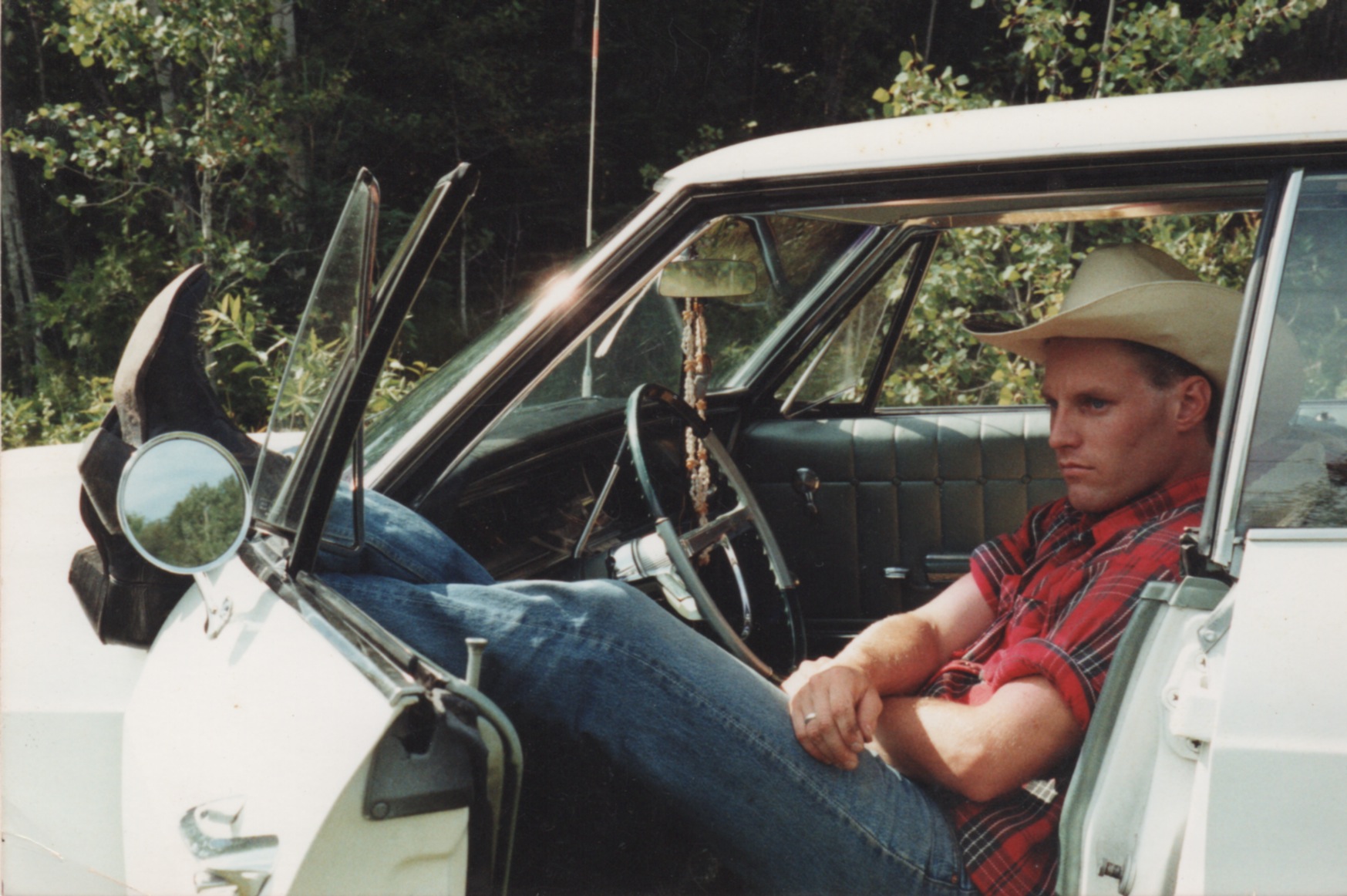

I had been riding a very slow drag that seemed to pick up single boxcars here and there, then venture calmly on. The freight had left Wisconsin where I had boarded her and had run into Minnesota at night fall on that increasingly cold early October day. After nightfall the train just stopped for what seemed forever. I couldn’t hear anything, so I slunk out of my boxcar and walked beside the maybe 30 car long drag until I saw a tiny lit barroom across a rural highway attached to a ramshackle house. Since I was pretty cold by then, but also feeling rather cocky that I’d ridden freights all day long—even if at one point the train had headed backwards, this to attach a car way up a siding—I entered the bar, setting my leather pack politely by the door. One man in a red plaid shirt, with a blue handkerchief tied around his neck sat working a glass of draft on one of the five stools in the dimly lit narrow room. The middle-aged extremely chesty barmaid asked me what I wanted. Not daring to order a beer at 17, I said, “You know what town I’m in?”

She told me, and then said, “Old Style okay?”

I nodded and in disbelief watched as a fresh glass of draft was set before me just as calmly as in a dream. I worked my beer, delighted but mum. The plaid shirt and barmaid continued talking, laughing together, obviously quite happy. After my second beer, which will probably be the two best tasting beers of my life, plaid shirt turned to me:

“You ready, partner?”

I looked behind me although I knew I was the only other person there.

“Excuse me, sir?”

“Ready to go?”

“Sorry, I’m not sure I understand.”

“We rode in together, right?”

I was really worried now, but the engineer clapped me on the shoulder and said, “Come on, I’ll let you ride in one of the units since she’s a chilly one tonight. But don’t touch anything, okay?”

And that’s how I arrived in Saint Paul!

From the novel Holed Up:

Chapter 4

I’m leaning up against an abandoned railroad station, the sun on my face, looking west. The Great Plains are flat, different than I’m used to, the railroad tracks are two straight lines touching at the horizon. I’ve never been this far west before and everything seems different. The sky is bigger and bluer with giant clouds, the cornfields smell sweeter, as does the wind that I imagine travels all the way from the snow on top of the Rocky Mountains. A diesel horn is blowing in the distance. I’ve never hopped a train before, but I’m going to try now.

He stopped reading. He hated it. This writing stuff was a lot more difficult than he’d figured. How was the reader supposed to know how he’d felt from that? Or care? That he’d stood on the weedy cement slip of the station, the cool early-autumn wind fragrant from the fields, the light crystalline, the hot sun on his face, that much was true; but how about his hope that the sun might burn up some of his blemishes after he’d washed his face from his canteen, or how his body and mind were humming with excitement because he was finally going to hop his first freight and ride it through the West—The West—of which he’d only dreamed, and then the headlight approaching, the wailing of the diesel horn same as the shout in his throat, the train drawing closer, the rumble intensifying, his mind at a perfect junction of poetry and reality, freedom and pure joy mounting to a pitch until he thought he might explode. And then the engineer waving, and he, uncertain, waving back, and then the boxcars, some empty, flooding past in a rust-colored wall, and he leapt from the station platform, sprinting madly beside the train along the uneven gravel roadbed, slinging his pack onboard an empty boxcar, his palms on the rough wood floor—he’d practiced so many times in freight yards, but now, he’s doing it for real, like the first time you ease your penis into a woman and you can’t believe it’s actually happening, which at sixteen hadn’t, so this would have to do—and he’s in, lying on his back, his heart and lungs hammering with the cadence of the wheels under him, then he’s sitting up and he’s riding a freight train. He, Jimmy Hakken, was riding a freight headed to the great West! That the train stopped after about a mile and backed up, what did that matter?

How could he write all that? Certainly not by describing some wind gliding down an imaginary mountain. He felt like chucking the computer through a window.

“Good old Jimmy Hakken!” That was an excerpt from my novel where Jimmy is living in Scoggton, Maine, waiting to execute Wendell Alden II, attempting to write about his life to pass the time.

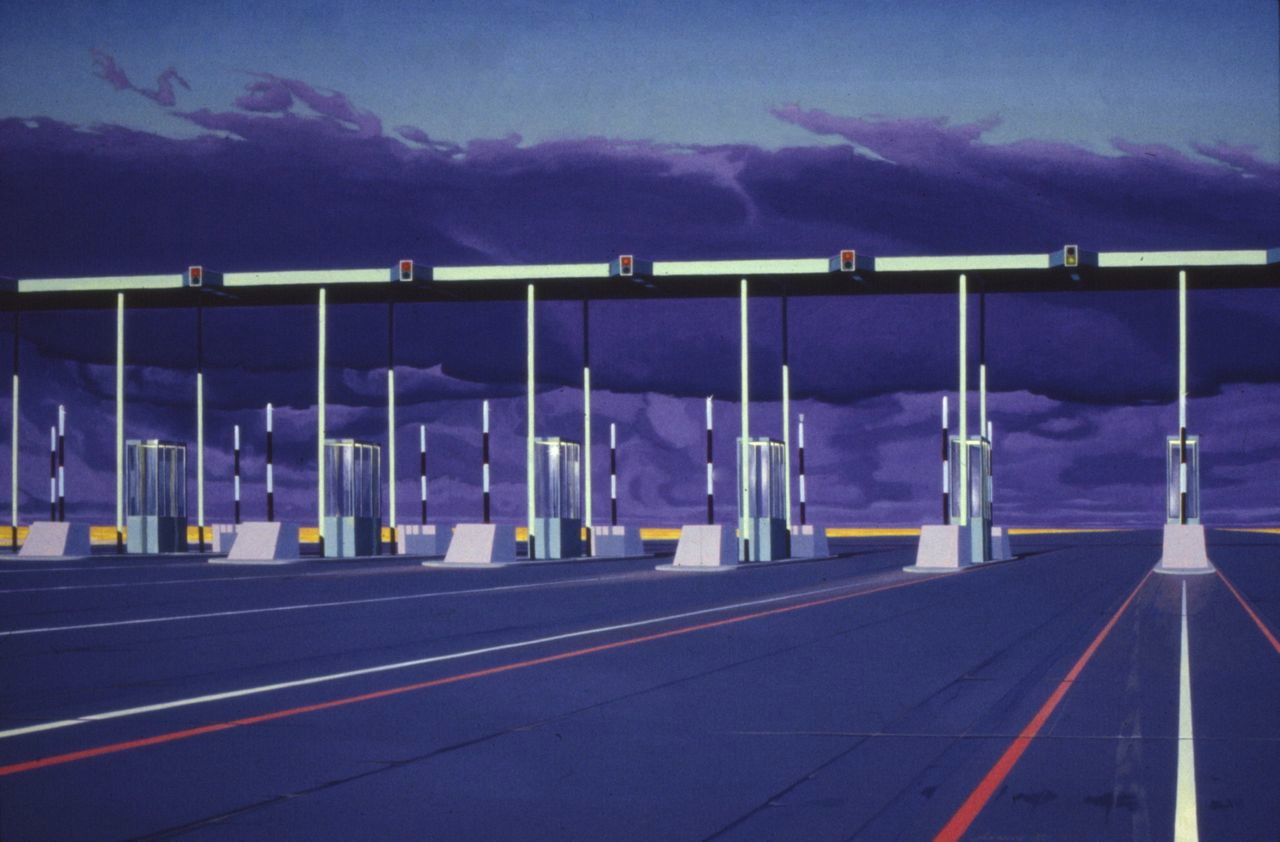

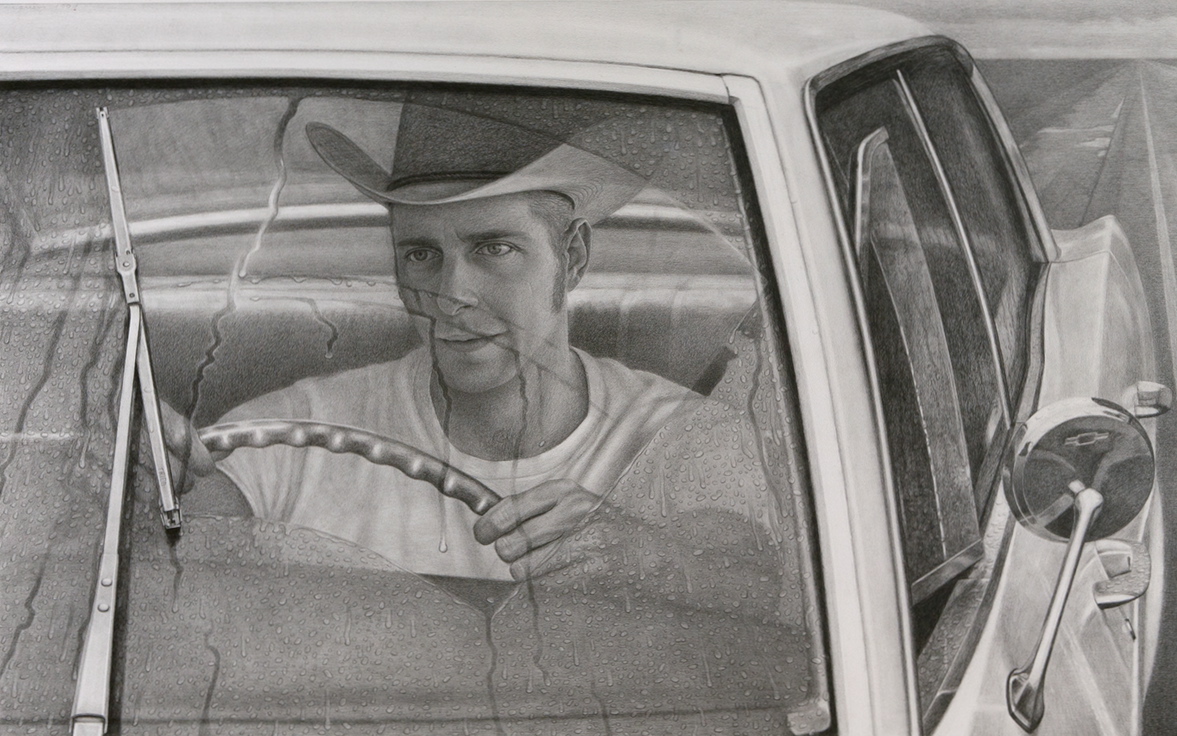

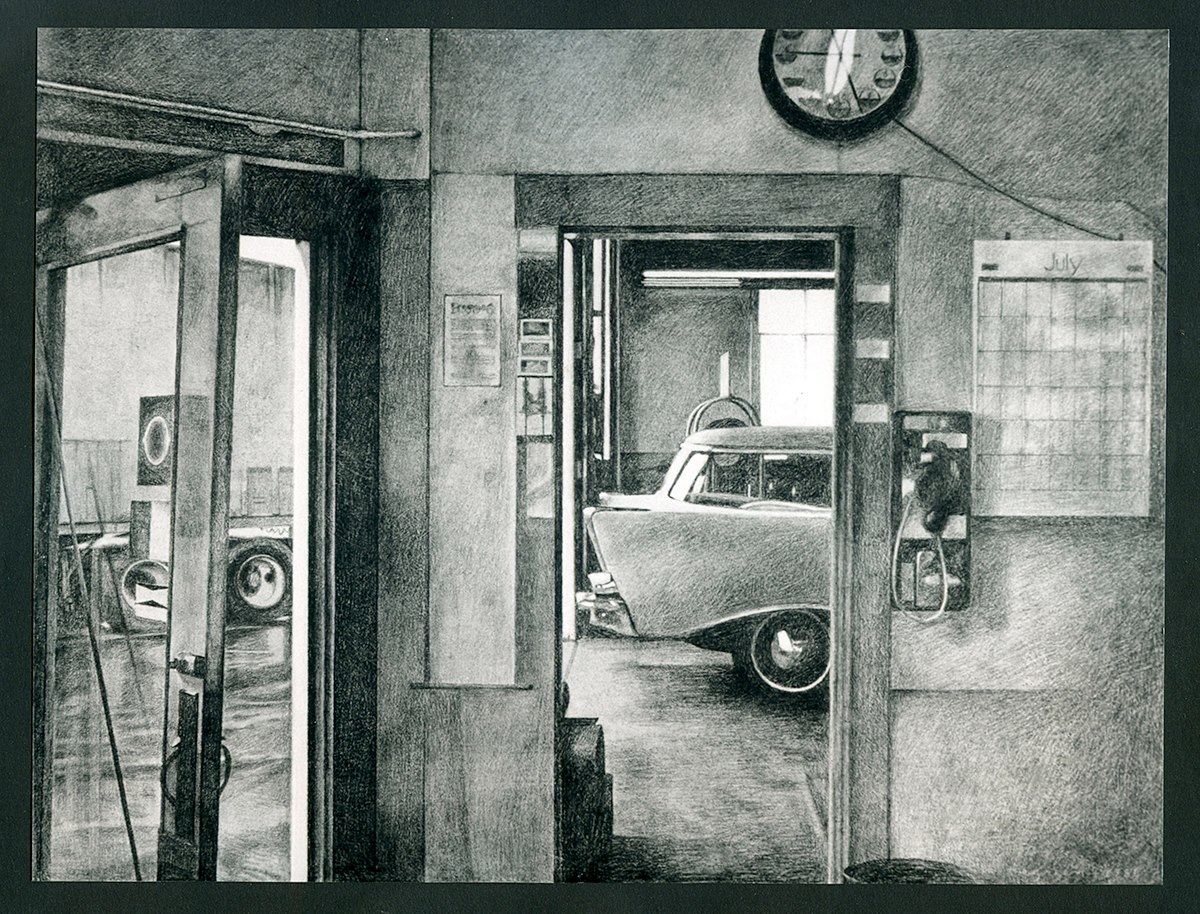

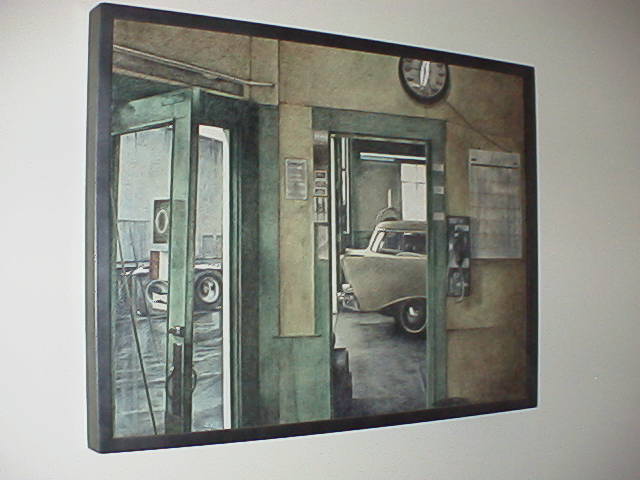

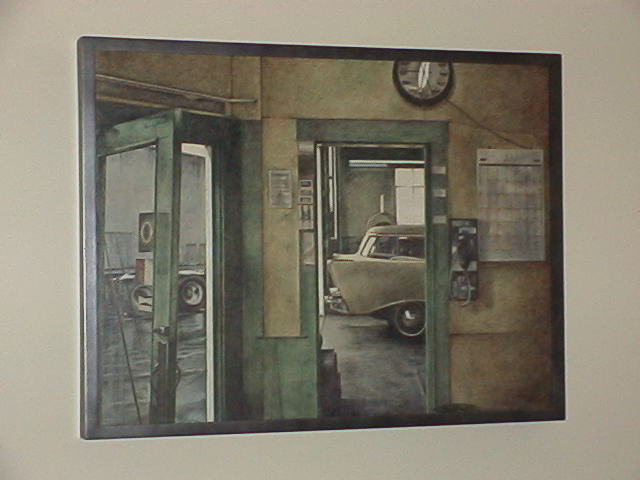

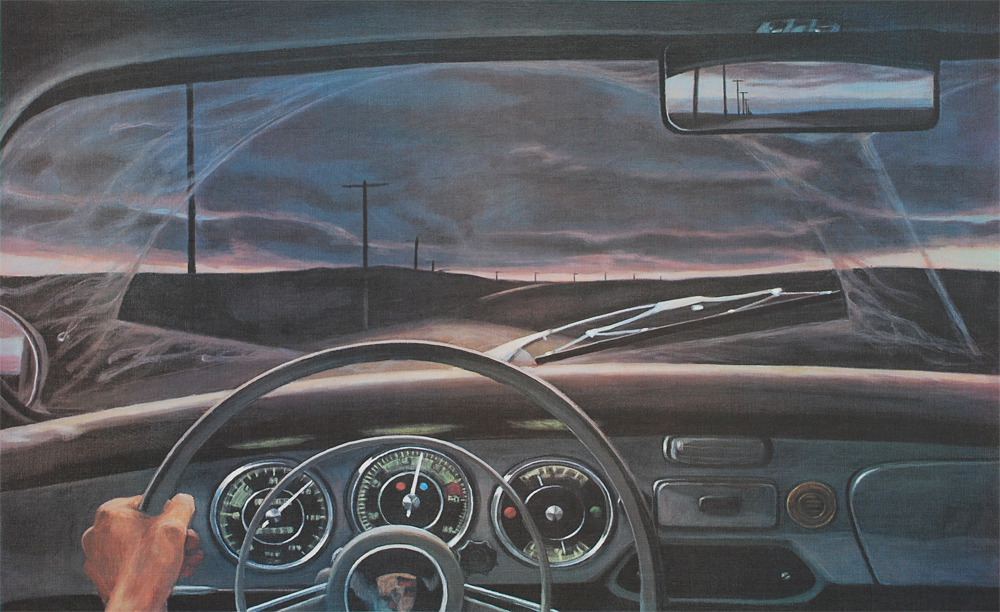

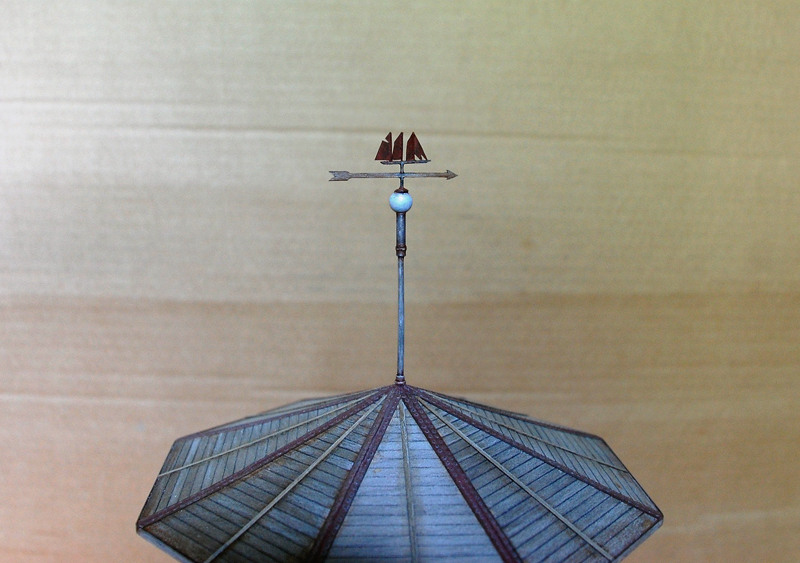

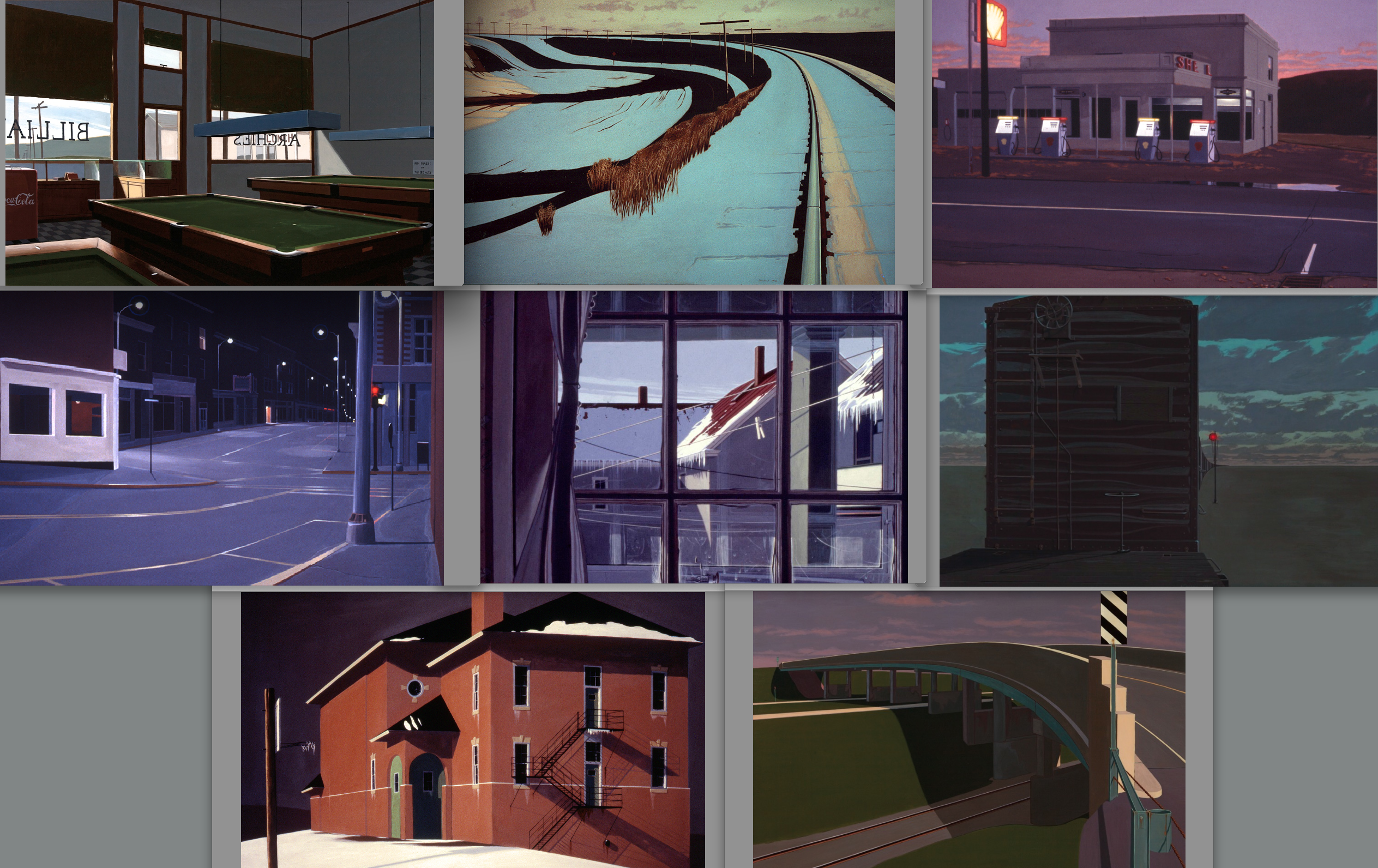

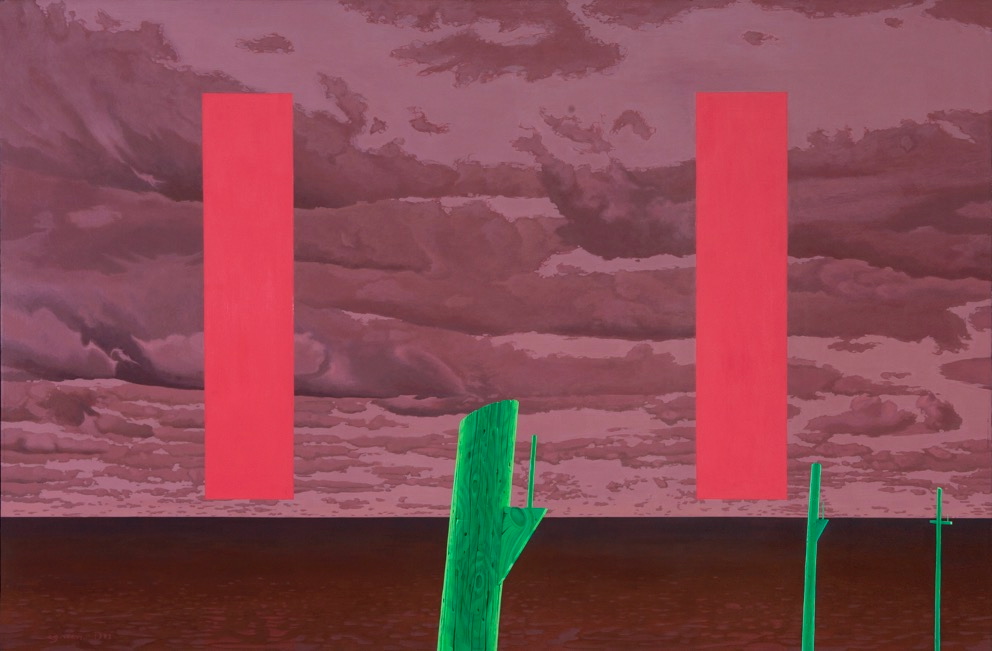

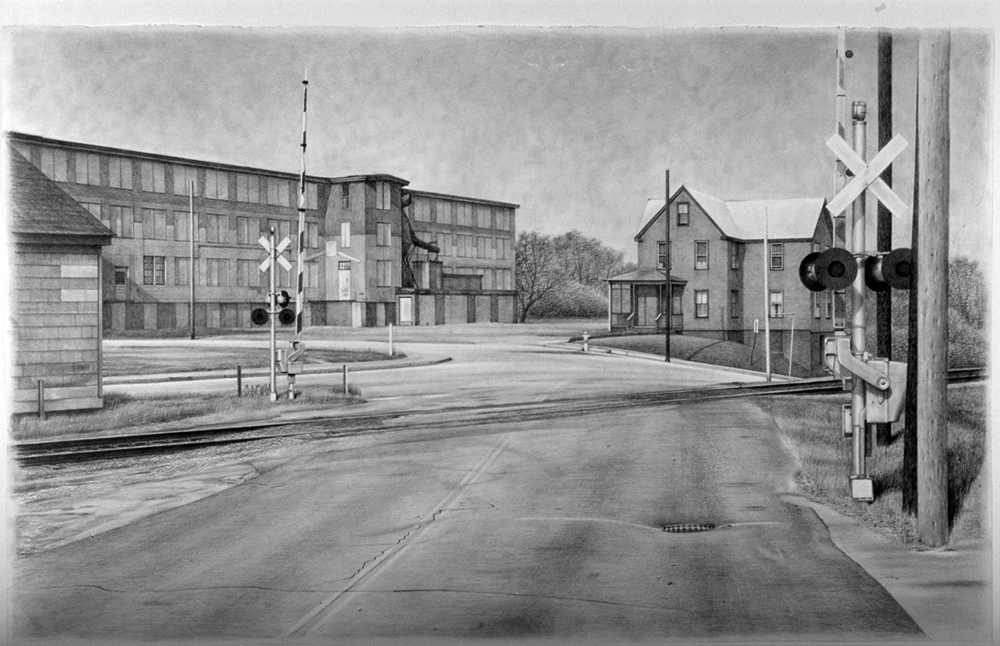

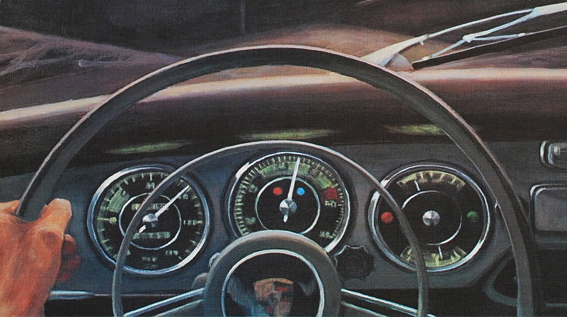

This is a terrible photograph of a painting I did at 17 years old shortly after I returned from riding freights in 1974. It was an acrylic on about a 50 inch panel painted too quickly (probably a couple days) and completely from memory. I destroyed it because I wasn’t achieving what I wanted from the image, mainly I didn’t care for the surface quality, not aware of painting in layers. For instance, in 1977 I destroyed 10 out of 11 paintings, keeping only the poolroom. I was self-taught and there were many things I had not figured out yet. Still, the image has something worthwhile now in a historical context. The moment was a freight train waiting on a passing siding somewhere in Montana, the burnt wheat fields striped by the cut wheat fields very stunning visually, a hotshot about to blast by in a simply overwhelming rush of sound and energy. The hobo I was riding with warned me about the suction while standing in the door and probably saved my life.

Okay, back to the 1980s:

We came upon Canyon Ferry Lake in the distance, past Helena, great wide burnt-grass rolling plains. Finally at evening we reached Missoula, Montana where the freight got humped. Out of the hot sun that baked the Missoula yard, I walked that evening into town with a rather worn skinny tramp whose heel on his cowboot boot was missing so he kind of limped along as if he were crippled, which didn’t seem to bother him at all. We passed along shaded streets, the high dry hills ochre in the distance, arrived at a small park more just a vacant triangle of grassy land among the houses. Dancing on this grass was over a dozen pretty girls in very scant rainbow-colored leotards, one of them calling out commands. Man, it really knocked that hobo and myself apart—from raw reality to this dream in a few blocks. I figured I was in a Fellini film. Anyway, we found a supermarket and bought Olympia beer for me and more Thunderbird for the tramps back in the yard.

And the reality fictionalized inside Jimmy Hakken’s mind:

Jimmy stopped and leaned back in his chair. That next day, he’d ridden with Bill as far as the freight yard in Billings. He could still see the old hobo walking toward his hometown, the warm afternoon sun on his back, a tired gait taking him over a couple dozen track rails until he was lost from sight. He’d been surprised at how sad it was to see him go—the loss of all his tobacco and food aside. After waiting in the empty boxcar for a lonely hour, Jimmy had decided to head into town himself, at least buy a few things; he was starving. He’d lied to Bill about money, telling him he had none when there was some hidden under the inner sole of his shoe. At the time he didn’t realize everyone hid money there.

As he’d walked into town with his pack, through neat rows of nearly identical suburban houses, he’d come upon a small park. On the bright green September grass raked by afternoon sun, a dozen girls had danced in differently colored leotards, all turning in unison. To his young eyes they were prismatic angels. He’d stood and watched, fantasies accelerating in his mind like a freight train with a green board. The dancing women were so surreal it made everything seem possible. He’d find his father in California. They’d go to Las Vegas together. His dad would have the money to place on the roulette table, the wheel would turn exactly on the specified hour, and the little steel ball would lock onto their number. It could work; against all odds, it would work. And why not? Didn’t everyone have an even chance at being lucky? His dad would slap him on the back, tousle his hair. His dad would love him for being a hero. And beautiful girls in leotards would fall at his feet, him, the unwanted mill-town kid.

Jimmy jerked to his feet and headed for the fridge. Now the beer was shouting.

It was well after dark when the freight finally got made up, and I attempted to sleep as it lumbered out of the yard tracks, believing we were headed west. But when I awoke and looked out the door, I realized we were still stuck in the Missoula yard. I couldn’t understand that, but as I’ve mentioned, hoboing is patience. During my first frieght run as a teenager, I would be bored waiting and just hop any train going anywhere, just to be rolling, but retracing the exact same line a couple days later felt odd as well, not that any of this really mattered to me. I was just delighted in being out there.

That morning was extremely frosty as I waited for the sun to reach inside the box. The Rockies are cold even in July even for a New Englander! We followed Clark Fork River through to Lake Pend Oreille, the land fully pined with large powerful sweeps of dark monstrous trees lifting from each bank, the rail line fitted in along the south side of the lake. My attention was divided between these overwhelming views of raw nature and an amazingly raunchy pornography magazine that the heel-less tramp had offered me—he having already read it cover to cover. I left it in the car for the next traveler. This struck me as humorous, this hobo library, rolling literature of the worst kind, passed from hobo to hobo around the country. But the contrast between the wilderness, the mountain peaks in morning light, and the glossy images of spread female legs was befitting the freights.

On a freight train

above wet glistening pink

deep monstrous pine.

We tracked over a long bridge at Sandpoint, Idaho, and then eight miles outside of Spokane, Washington, the hogger law was sanctioned. A railroad truck picked up the engine crew. The freight sat sided, spilling tramps, everyone grumbling and mulling around, their much anticipated drunk stalled on a siding. I laughed, pulled on a clean T-shirt, waved good-bye, and began hitchhiking, reaching Spokane before the engineer.

For me, Spokane will always be the place where I watched a man die who I might have saved, as well as the place where I almost died myself, this when I was 17. That day had a huge effect on me, and ended my first freight run. Some things really scare you and the memory of that day still bothers me. I will let Jimmy Hakken tell it, but it’s my story:

In Pasco, Jimmy’d left his train and walked along the tracks.

There is this scarred, abandoned icehouse with a bunch of hobos under it. They’re drinking wine. As I walk by, one of them waves. I realize they take me for a tramp, which secretly pleases me. I stop and go over. The guy who’d waved says, “Got any smoke?” There’s four of them so I shake my head.

“Where you headed?”

“Portland.”

“Ain’t a train till this afternoon.”

“You going to Portland?”

“We’re all headed there. You want some wine?”

It’s Thunderbird, and the thought of drinking after these guys is not pleasant. I shake my head.

He liked scarred because the timber frame of that ancient structure might have been recycled from the ark, but his drinking after the hobos—their gapped-tooth mouths, their scabbed lips, their rotting gums—not pleasant hardly matched his disgust. And the dialogue about tobacco—though it always happened that way, the reader already knew it. If there were ever going to be any readers. Why would anybody want to read about some kid trying to find his father?

He got up and circled the apartment. He couldn’t shake the memory of that day. It was the first time he’d watched someone die, and the worst part—he didn’t try to save the guy.

He’d joined the hobos in their drinking, surreptitiously wiping the bottle with his shirt. By afternoon everyone was drunk. Someone who claimed to be a bank robber tried to befriend him. Wearing unsoiled khakis and a fairly new jacket, the guy had teeth, and seemed more intelligent than your average hobo. The oddest thing was his clean-shaven jaw, so blue it might have been in a cartoon. After demonstrating to Jimmy how to steal wine and beer out of a trackside grocery, the thief explained in detail how to crack safes—which drills, which chisels. He doubted the thief knew what he was talking about, but listened anyway. Then trouble started. He was soon to learn that drinking among bums usually led to violence.

Two guys began arguing. A sledgehammer of a guy with hair that looked as if it mopped floors, was insisting he was a hobo. Another tramp was shaking his head. “You ain’t no ‘bo—you’re a bum.” He said it as calmly as a judge with a verdict. “You never travel, you never work, so you’re a bum.” Sledge staggered upright, yelling. The tramp stood as well, his ill-fitting overalls hanging on his tiny frame. “I don’t give a damn what you say—you’re a bum, and that’s the end of it.” In response, Sledge grabbed a scrap of lumber and whacked the tramp in the head with it. He tried to cover up with his childlike hands, but the second blow brought blood. No one seemed to care. Jimmy got to his feet, and coming from behind, wrenched the weapon from the large man’s grip. Sledge turned on him now, bellowing. Jimmy held the stick ready like a baseball bat, his hands shaking.

“Leave the kid alone.” It was the thief.

“Git out-a my way. This got nothin’ do with you.”

“You heard me. Leave it.” He turned to Jimmy: “Come on,” gathered his bedroll and battered suitcase.

Jimmy backed away from Sledge and shouldered his pack.

“I’ll fine ya, ya punk,” called Sledge to their backs. “I’ll fine ya, and I’ll kill ya. It won’t matter where ya hide, I’ll fine ya and kill ya.”

“Ugly drunk,” said the thief. Jimmy tossed away the stick.

As they walked, a long row of freight cars began creaking and moving a few tracks over. The thief turned to him: “We can still catch it. We better get you out a here, ‘fore he starts lookin’.” There weren’t any boxcars, so the thief grabbed the ladder on a hopper car and pulled himself onboard. “Come on,” he yelled, his hand outstretched. Jimmy just made the train. It was ten minutes later, as they tracked into the desert, that he realized what was wrong.

“We’re headed east.”

“Don’t matter.”

“When do you think this freight will stop?”

“No idea.” He opened the suitcase and pulled out a pint of tequila, offered it.

Jimmy shook his head.

“Suit yourself.” The thief shrugged, tipped the bottle, licked his lips.

The car they rode on was a massive cylinder that held dry powdered cement, poured in at the top through hatches and released out the bottom through hinged doors. At each end were diamond-grated platforms under the sloped angle of the enormous drum, one taken up by brake machinery. It was on the other that the thief and Jimmy crouched, only a three-inch lip of metal around the perimeter protecting them from rolling off onto the roadbed and under the wheels. As the freight reached speed, it became too noisy to talk. He was miserable—headed away from his father, his temples pounding from the cheap wine and beer.

Evening brought cold, and the thief got drunker. He opened a second pint. His suitcase seemed to be filled with them and little else. When night left only a brutal red blur at the horizon, the thief sidled up next to him and mumbled something—the foul alcoholic breath, spit-covered lips touching his ear. With the clatter of the rails and the car, he couldn’t understand at first. But when the guy reached toward him, grabbed him by the thigh and tried to pull down his zipper, he did. Jimmy punched him in the throat. The man fell backwards and just lay there on his side. Then, like a wounded animal, he retreated on hands and knees to the other side of the platform, his eyes wet in the last light. Jimmy stayed wary, but the thief just muttered to himself and kept pulling at the pint.

The freight left the black desert and entered the outskirts of Spokane, slowing only slightly, the city lights and the red swirl of crossing gates reassuring. Suddenly, the thief staggered to his feet, stood a long moment, swaying—Jimmy barely breathing. He pointed oddly at Jimmy, mumbling something. Then he turned clumsily and simply stepped into nothingness. Jimmy leapt to that side of the car. The body was still tumbling along the gravel as if it would never stop, and then it whacked soundlessly into a steel electrical box. All he could do was throw the man’s meager belongings out after him, the pints probably shattering when they hit the roadbed. In seconds it had all vanished in the darkness, but never in memory.

The freight is still going kind of fast. I head into the Spokane yard, but it doesn’t seem to be slowing much. I think of spending the night in the Idaho mountains, and I decide I might as well jump as freeze to death. At that point I didn’t know the secret of jumping off a moving train, which is to run like crazy when you’re in the air. I jump like I’m leaving a porch step. When I come to I’m looking at the night sky. My head feels wet. It’s blood. But I figure I did better than the other guy.

Back to 1980, the westbound freight rolled slowly out of Spokane, the paved city streets below chocked with cars, noon sun, hot-looking Western secretaries (healthy cornfed girls) going to lunch counters from air-conditioned offices, not noticing the hobo hanging in the boxcar, feet dangling, corncob pipe smoking so sweetly, but I noticed them, enjoyed their wiggling asses in tight summer dresses, their highheels and nylons over nicely defined calves. The land got sandy and then suddenly we were in the desert, which I’d first ridden with huge emotion on a full moon night in 1974 (poem below). I noticed my bare feet made bizarre black footprints on the boxcar floor, and it took me awhile to figure out the truth. It was volcanic ash, a very white gray, from Mount St. Helens, which had erupted some months early. I was stunned that the ash had travelled that far.

DISTANCE

One memory haunts more than all others.

It lies in the mind like full moonlight:

Cool, silver, green,

Like a loam of longed for love.

Through all these years it holds me,

Keeps me with its relentless purity.

“That which shall not be reft from thee,

That which can not be reft from thee.”

At a young age I saw the American West

For the first time from a boxcar door.

Everything now much bigger than I knew,

But in my sudden smallness

Came a strength—

A willingness without fear.

And so there see me in the October night,

And so there see me in harsh chill wind,

The desert by moonlight (Spokane to Pasco),

Moon so bright to eclipse all stars,

Sky an immense ringing iced silence,

The flatcar boards under worn shoes,

Patched corduroys flagging thin legs,

The drumming of metal wheels and rail,

The occasional cry of wheels and rail,

The freight train flying like a lost angel,

A mad phantom fleeing youth’s expectation.

But I am there, I am aboard,

Standing, huddled; silent, screaming.

God release me from this memory

So that I may just be average;

For then I knew I cared more

For beauty than for pain

And that there was no return.

Watch the signal lights,

Way out on the black arc

At the front of the train,

Watch the signal lights

Change from yellow to green to red.

These pure primaries against the monochrome

Of the desert night under that moon.

Ask me not to be a painter now,

Forbid what should be forbidden,

For it is unfair to feel so deeply.

That a life will be spent gaining inches

When this distance is read in miles.

Poem written in 1998

I rolled into Pasco, Washington reading boxcar graffiti—I was only a few days away from Herby who always drew a Mexican sitting under a palm tree—and thus began the odyssey of 32 hrs of beer drinking. I suppose I could blame the dryness of the desert covered in volvanic ash, but it’s the only time I’ve drunk for that long. Maybe it was the joy of riding across the entire nation once again. There is a feeling of the coast to coast America run that is unrivaled. What a great landmass we have!

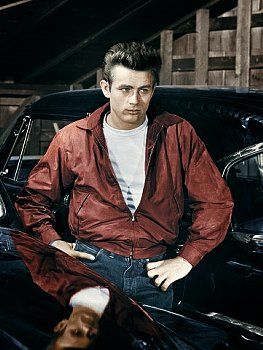

Leaving the freight, I walked well over five miles past western motels with gorgeous 1950’s neon signs into the outskirts of Pasco along myriad freight cars as the sun burned down, everything shimmering below a pale azure sky broken only by red and lime green motel signs. I stopped at a pay phone to note my reflection in the chrome not to make a call. Then found a store that sold beer. After purchase, I sat in the shade and watched the street show of Hispanic greasers in black T-shirts washing hopped up Chevys at a carwash. A street fight started, two gangs standing by their shiny rides, a cloud of tire smoke left drifting in the heat when they exit, chrome flashing as cars gun by, cute girls in sweaty tank tops and tight jeans or hot pants, pert tits in the sun. It really feels like the West to me, and I’m indescribably happy just to be there a part of it all. (Life hadn’t battered me yet, I still lived with so much hope and desire and love for everything, even my dad was still alive.)

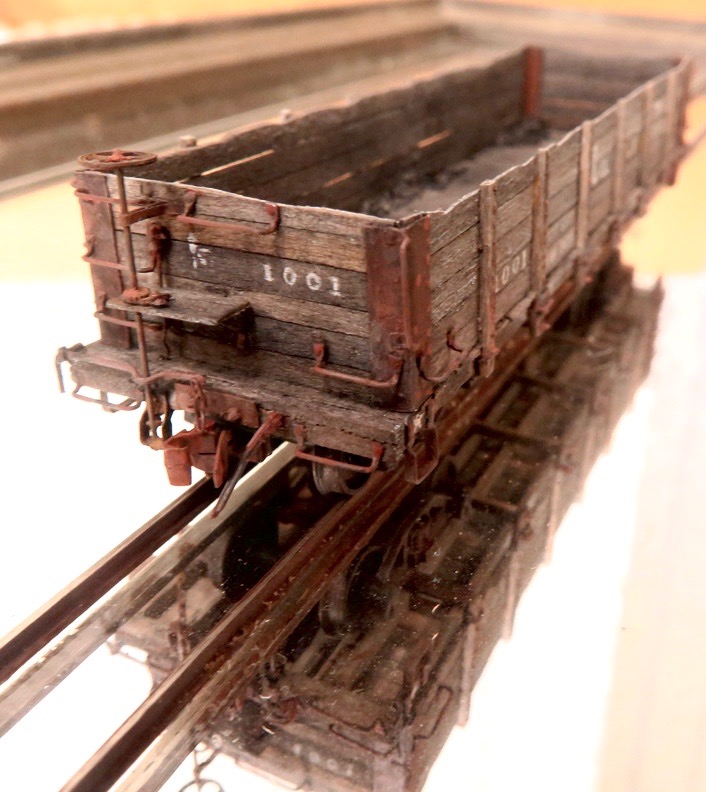

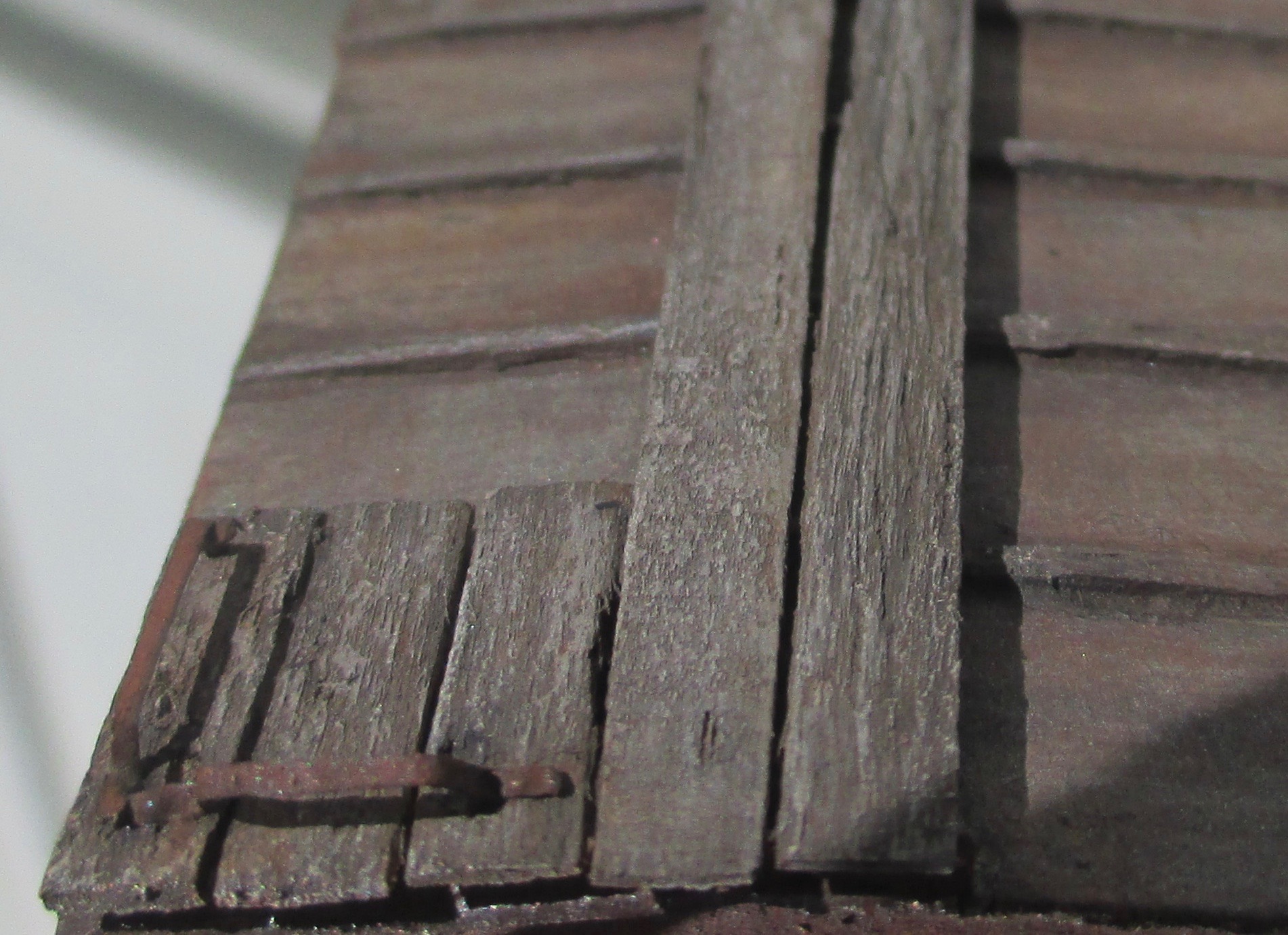

After a few reviving beers, I walked slowly up to the closer end of the railyard where outbounds leave for the coast and where hobos have waited many years: witness the dark graffiti covered wood hide of the ancient ice house. The strcture loomed in the hot evening light behind us, the worn pitted cement, the weathered gray black splintered timbers a crisscross of lines. A perfect place to drink, wait for departing trains, and share a few tales with fellow hobos.

We sat about on crates and drank beer with yet another highway overpass too near, big trucks passing mmm kwang kwwang. I talked with a very clean hobo—a true rarity—Clarence as darkness gradually came down like a slow fine rain. Drunk hobos staggered by and we kept working beers and talking about his missed relations with wives and woman and how they took his money, etc. Also discussed the differences between black and white women, their asses, what they wanted. Clarence being black refused to have anything to do with black women. He told me where good places were to pick up girls around the country, his favorite being Eugene, Oregon. A big moon rose above us, its shine on the myriad rails, the huge yard spreading out in the warm summer air, in the distance far off Pasco Main Street lights. A fight started because two tramps who had lost their beer, which is a regular occurrence among drunks. Clarence and I calm them down. Long freights with multiple engines start leaving; we yell to the engineers: “Portland?” Heads shake, diesels grumble, depart.

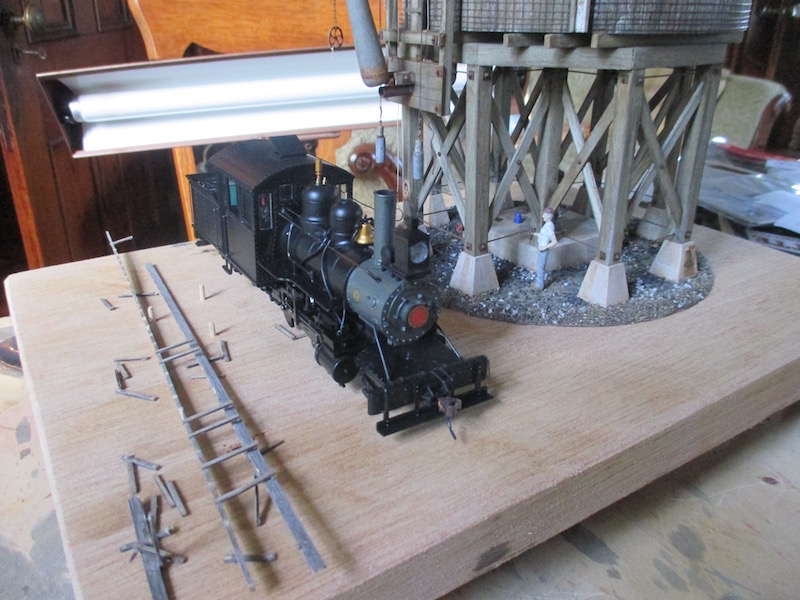

My freight is finally about to leave—a cement train. The diesel headlight makes the icehouse leap out as we stumble down the gravel, dozens of drunk hobos yelling, moaning, crawling onto cement cars, which have little platforms that ride out over the wheels, a mere lip of metal keeps you from falling between the cars. [Always choose the end without the brake equipment.] I slept strangely, kept waking listening to the wheels under my ear kuchunkadunk a kuchoonkadoonca feeling the warm night wind, stars in the desert sky. Freight stopped in Wishram at the first bluing of dawn.

CEMENT CARS

When I was seventeen years old,

Somewhere west of Fargo, North Dakota,

I jumped between two cement cars,

Two railroad cars rolling seventy: leapt

Over the blurred gravel roadbed

Over the two grinding couplers

Over the shrieking wheels

Back and forth past death

From one swaying metal platform

To the other I jumped:

Over the arc of my fear.

I wanted to be a poet,

I wanted to touch all nature,

I wanted to be a young hero.

Then, some weeks later,

Again riding on a cement car,

This time east toward Spokane,

I watched the drunk tramp beside me

Just walk off.

I watched his body hit the gravel

One bounce and a sickening tumble.

I felt my guilt flare:

I could have tried to stop him,

But instinct had held me back.

I threw off his pathetic baggage,

Though he was long gone in the distance,

Then sat huddled in the growing darkness.

Six years later,

I rode through a desert night,

I laid on that same platform,

A three-inch lip holding me

From rolling off and under the wheels

As I tried to sleep,

A warm rack of beer vibrating

Beside me in that soft night wind.

The moonlight moving over my eyelids

The banging of the cement car in my dreams

The clear smell of the desert in my dreams.

I slept and I slept.

Poem written in 1995

Sometimes you think you’ve entered a dream. That was my experience in Wishram, Washington on the Columbia River that morning, and I’ve always wanted to return, just to see if it was a manifestation or if it was real. But by now, the way everything changes, I’ll never know. As I walked past grumbling or snoring hobos, a lit diner appeared out of nowhere, out of the blue fog off the river, an apparition of perfection, and I opened the door to an Edward Hopper painting, even the waitress was a Hopper goddess. She poured me a fresh cup of coffee and went off to fix my potatoes, eggs and rye toast. (I had long ago given up eating four-legged animals.) Can you imagine how that breakfast tasted? It was the first real food since Barbara Verbrick’s delights. Makings things even better, the train crew ate there as well, so I had no worries about being set out.

Bill takes a wallet out of his jacket pocket. It’s long and cracked and worn round on the edges. After a long stare at the thing, he removes a folded piece of paper that looks worse than the wallet. He holds it up like a winning lottery ticket.

“Son, I’ve carried this for a dozen years. It was given me by a little Mexican fellur who said he was some kinda medicine man, but he spoke good English and rode the West. We caught the same flatcar one morning ridin’ along the Rio Grande. Guy looked a hundred years old. I had some beers in a bag, a little cool from the night air. And when I shared the beers with him, he give me this paper. So it’s being passed along. I don’t know where he got it. Feeling I had was that he wrote her up himself.”

His face all serious in the fire light, Bill hands me the dirty thing. I unfold it and it almost falls apart. On it are some numbers in a grid and a diagram. I keep looking, not wanting to putdown Bill’s gift, but I have no idea what it is.

“That, son, will make you a fortune. You see them numbers at the top? Them’s dates. You see them others? Them’s addresses. Next row? Them’s times. Then comes the key ones. They’re roulette numbers on a roulette wheel. The diagram shows you where in the casino the tables are. You know how roulette works?”

“Little bit.”

“Well, you hit a number it pays big-time. You see that number there, eight-five? Well, she’s coming up, as you know. Next year. And then you got yer month and yer day. Then you follow her down, and you got yer address. Them casinos is all in Las Vegas, Nevada. You hearda the place?”

I nodded. Who hadn’t?

“They’re all on the same big street. They call her the strip. You go there, find yer table, wait fer the exact time. She’s gotta be exact now.” He snapped his fingers. “Then you play yer number. She’ll hit, and yer a millionaire just like that.”

Bill is looking at me with his toothless grin like he just made me rich.

“But you never tried it?”

“Son, you got to raise at least a hundred to put on yer number. Now, I raised her one time, and I headed fer Las Vegas. No doubt about that. Trouble was, the thirst outran me fore I ever got there. And I ain’t raised that kinda money since.”

“But you think it’ll work?”

“You can’t be certain about nothin’, but I’ll tell you what. I asked that little Mexican fellur the same thing. He looked over at me and says fer me to watch. He takes an empty beer bottle. Now the freight, she’s flyin’ along past a rock wall on one sider us. He throws that bottle at the rock cut.” Bill made a throwing motion like you’d toss to home plate. “And you know what?” He waited until I shook my head. “She bounced. That there bottle didn’t break, she just bounced.” Bill shook his head and started laughing. “Damndest thing I ever seen.”

In reality, after my breakfast, I went to wash in the restroom, and on exit realized that the train crew was gone. I grabbed my pack, paper bag of warm beer, and ran. I barely managed to climb on a bulwark flatcar. At the same instant that I jumped on, a tiny Mexican tramp hopped on from the other side. We both sat back panting against the bulwark as a clear dawn opened around us. He was one of the smallest dirtiest men I’d ever seen, yet wore a pale-gray wide-brimmed felt hat that looked almost new, which I’m sure he treasured. He called himself Ray Panama, and I gave my road name Cody. After fifteen minutes, I decided to attempt a beer, and oddly, it wasn’t that terrible. “How ’bout a beer for breakfast?” I asked him. Of course Ray was delighted by my offer.

We rolled along the edge of the Columbia River, which along that stretch was as wide as a lake, huge sandy banks rising up hundreds of feet to where the tracks ran. Along the other bank, so far away, other trains pulled in the opposite direction. The sun hadn’t cleared the ridge, but the sky was an intense morning blue. Ray had an ancient Polaroid camera and kept snapping pictures (no film).

So we drank warm Rainer beer, and the vibration of the train created up to four-inch foam towers out of the bottle ends, which we found hilarious, everything delightful, particularly the Union Pacific trains across the river looking like bright yellow lines in the warming sun. One of my favorite moments, except for one tragic thing. Needing a pish from the flatcar at 75 miles an hour, Ray lost his hat. Ouch! It simply blew away forever. Somehow I’ve never gotten over that.

Ray gave me a chart which he prized that was supposed to allow a person to grow vegetables three times their normal size, if only you could figure out all the strange symbols and lines. After we finished each beer, we threw the bottles off the train against the rock cuts which were surprisingly close. They shattered wonderfully in firework-like explosions. Then I threw one bottle that ricocheted unbroken from the rock cut and then scampered across the flatcar wooden decking to rest base up in the middle of the car. Panama decided the bottle was bewitched and asked if he could have it. “Of course!” I doubted it made up for his gorgeous hat, but maybe it served him well somehow. One can only hope.

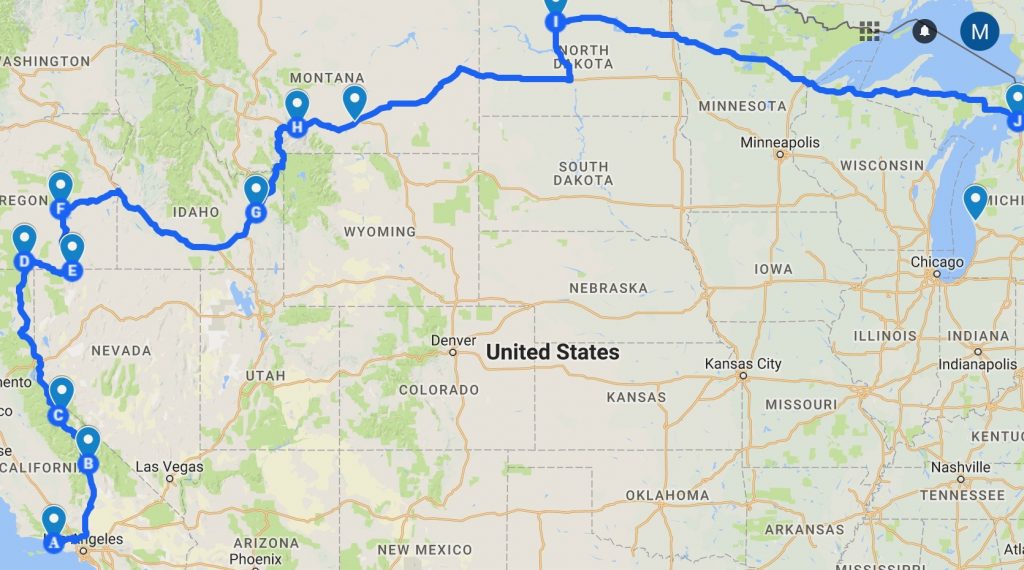

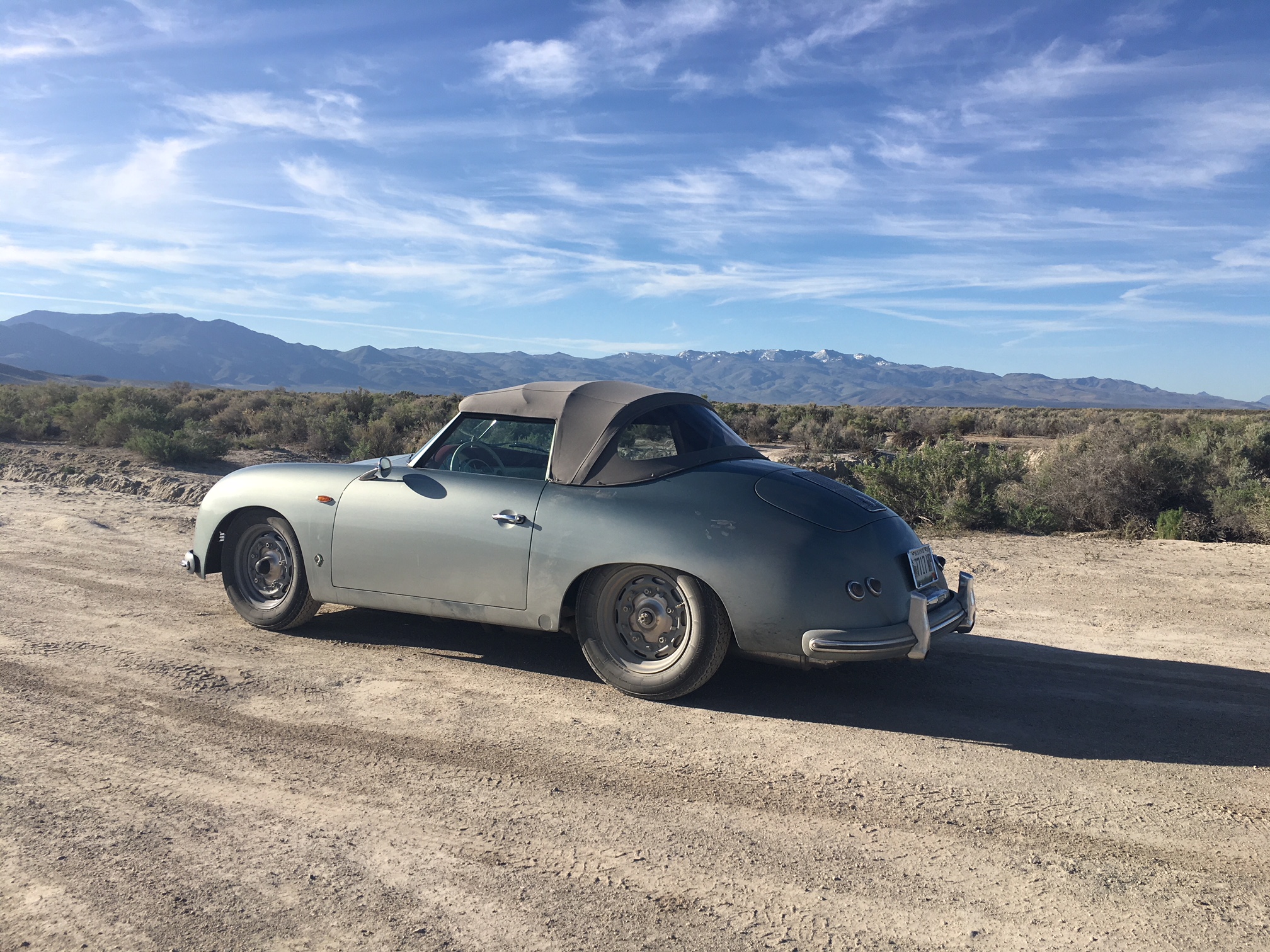

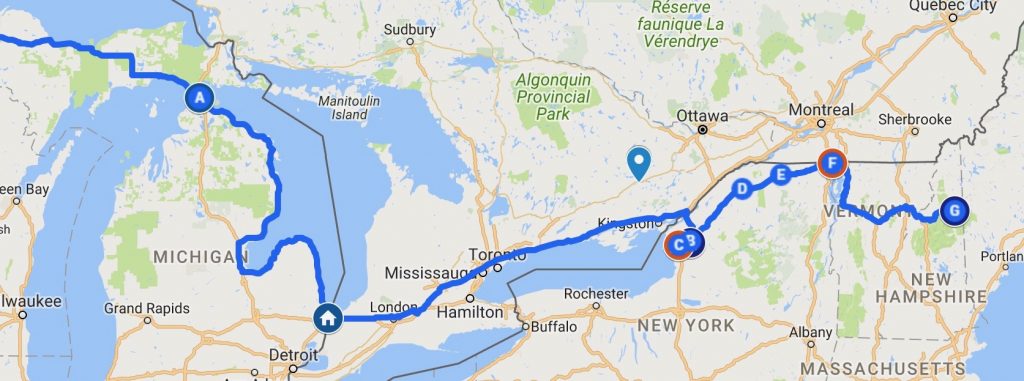

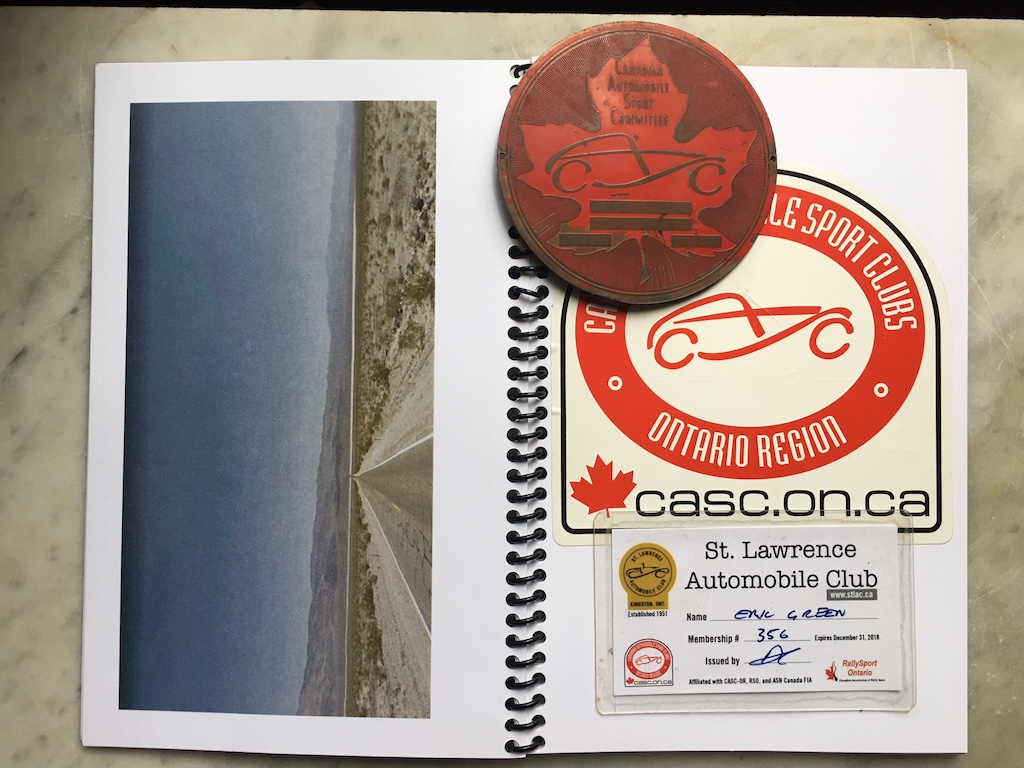

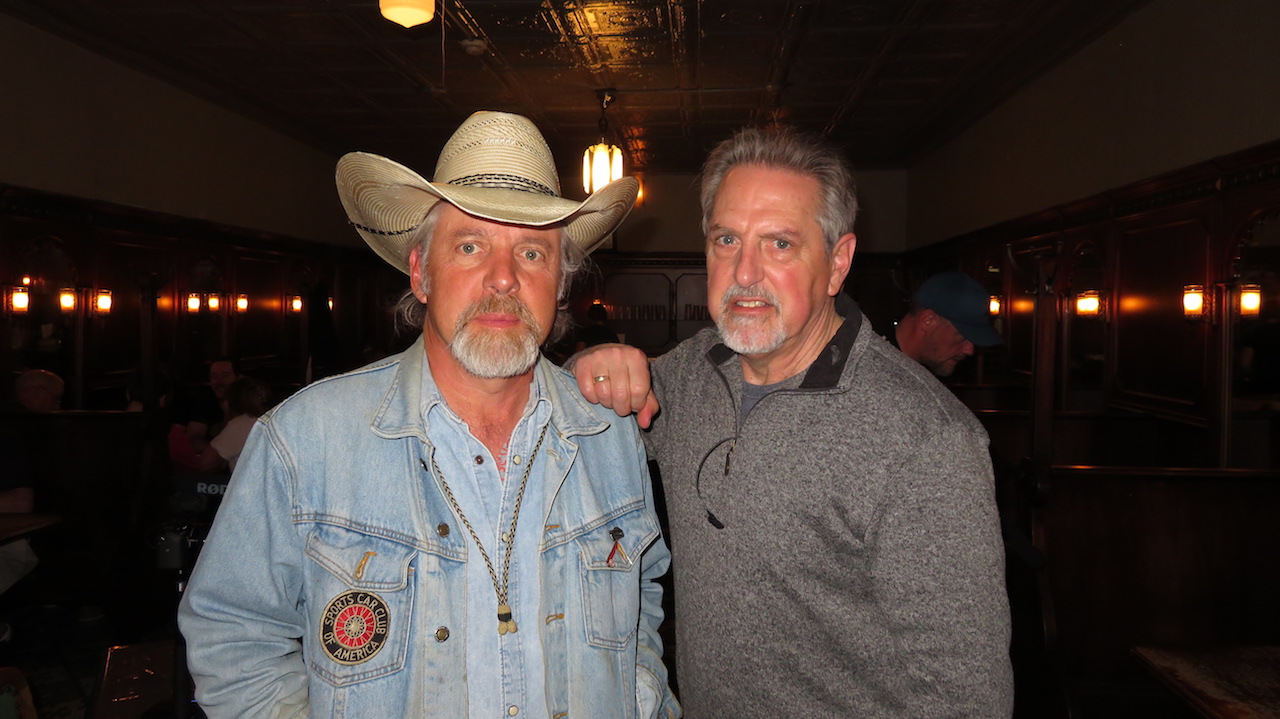

Garrett in Boxter simply amazing wingman. Could not find anyone better ever. Cheers to such a humorous calm road partner. Does these drive-bys at nearly 120 mph. Such joy! Amanda, of course, is a dream in the passenger seat. Only dislikes high-speed corners with huge drop-offs and no guard rails on her side.

Garrett in Boxter simply amazing wingman. Could not find anyone better ever. Cheers to such a humorous calm road partner. Does these drive-bys at nearly 120 mph. Such joy! Amanda, of course, is a dream in the passenger seat. Only dislikes high-speed corners with huge drop-offs and no guard rails on her side.

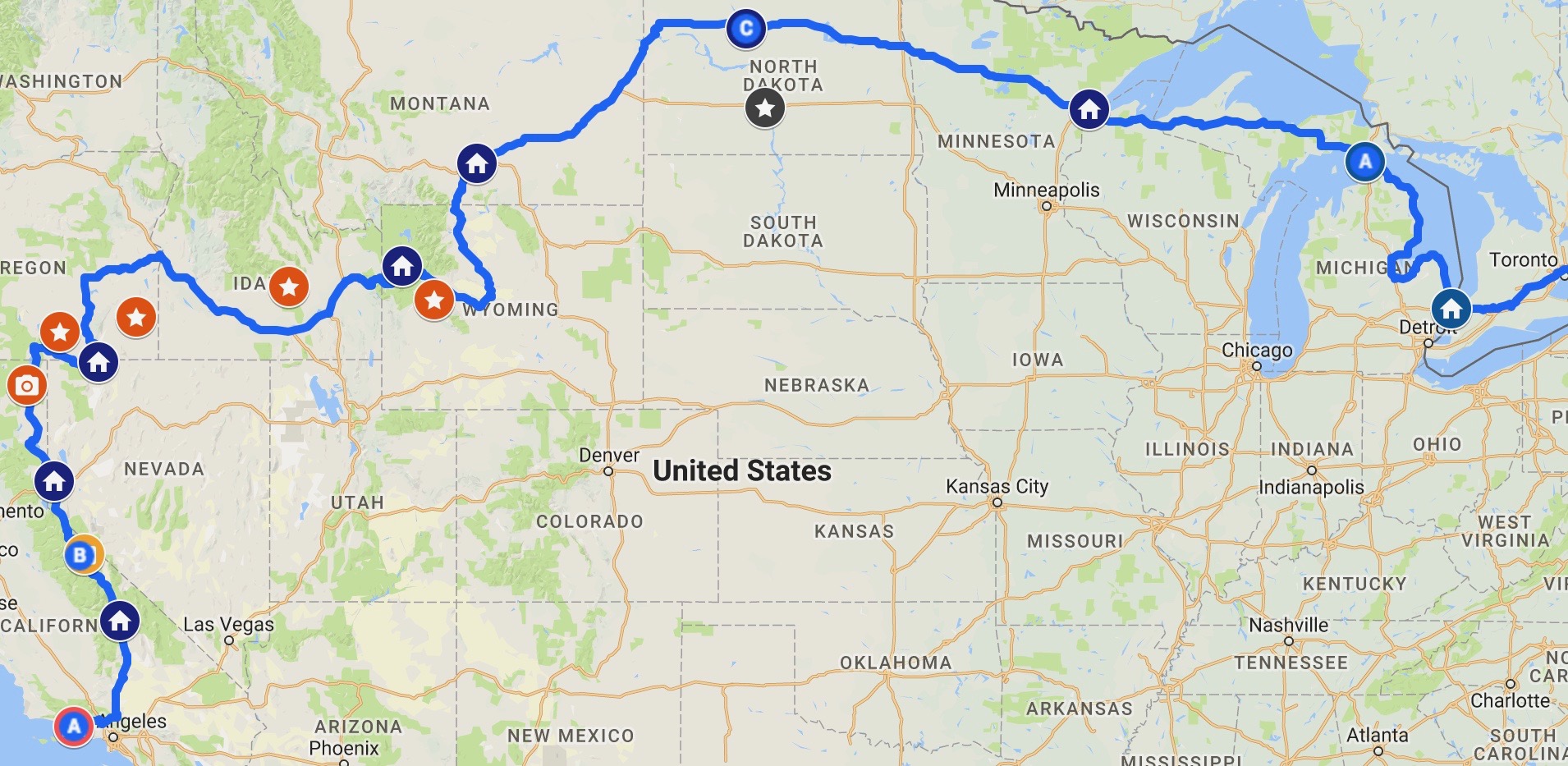

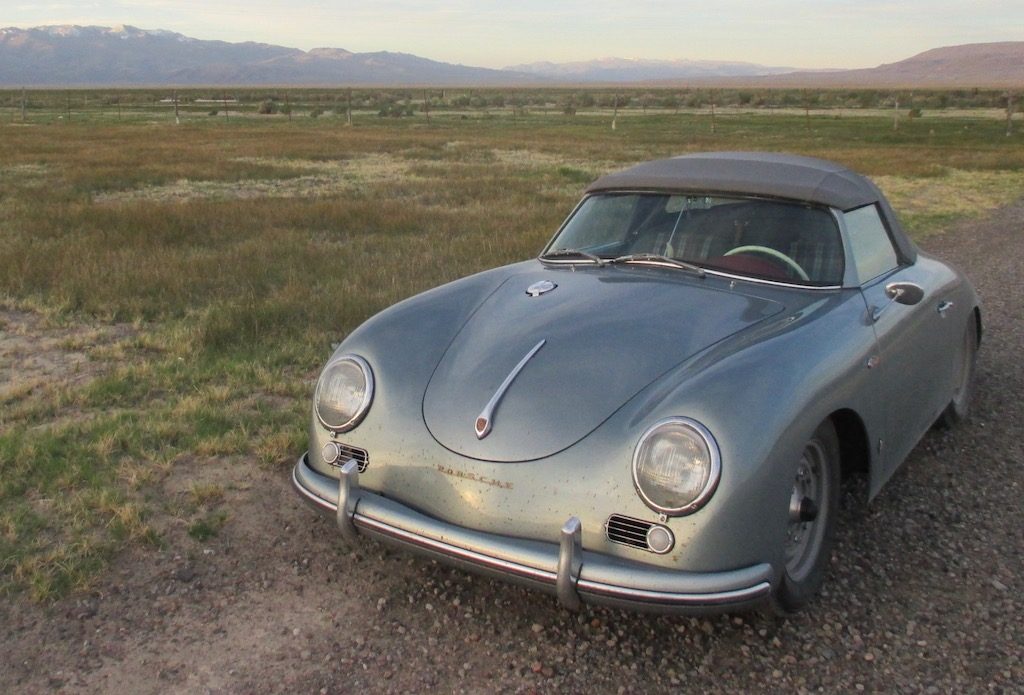

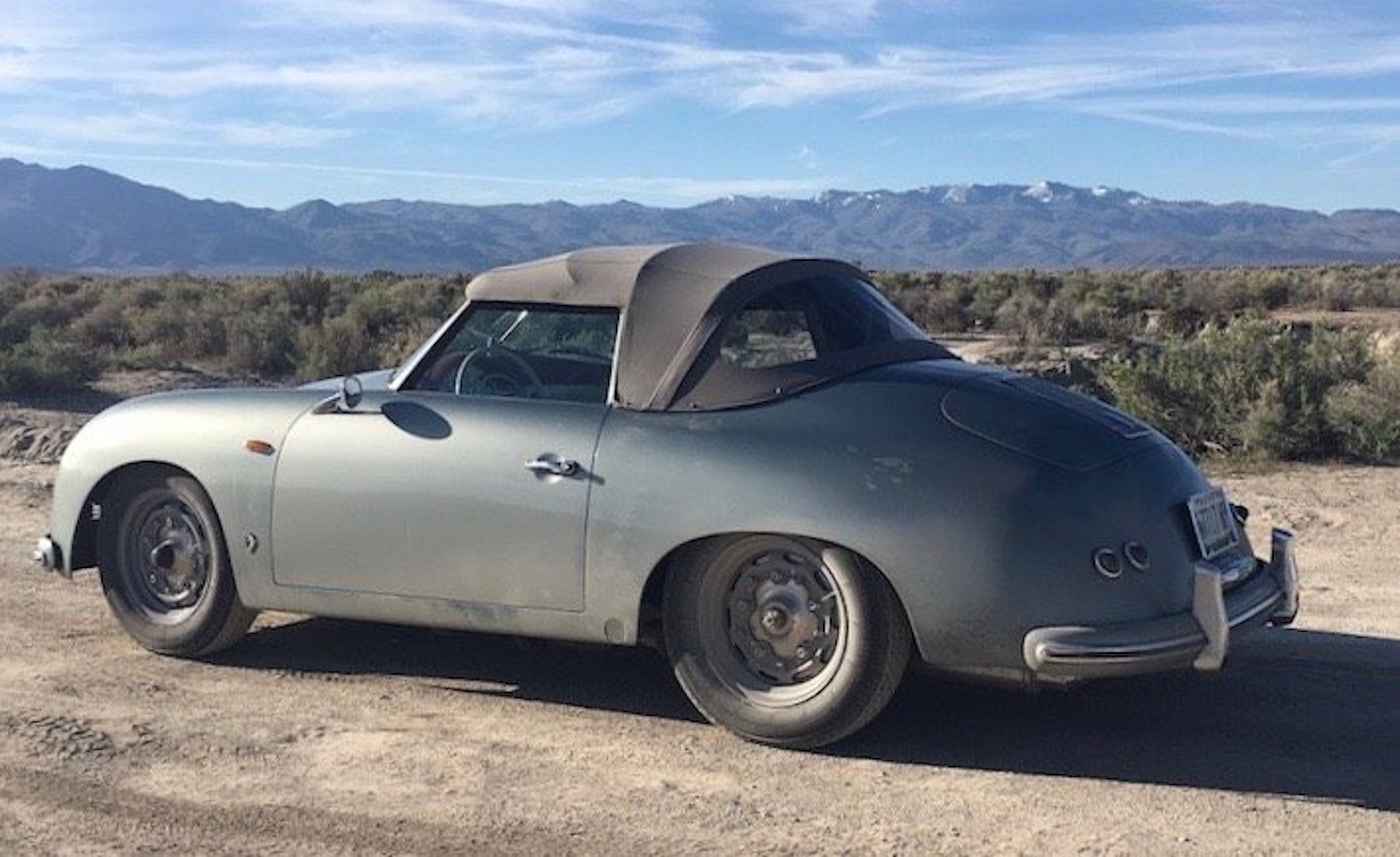

Dawn at Denio Junction, Nevada, May 8th 2018, Amanda’s birthday

Dawn at Denio Junction, Nevada, May 8th 2018, Amanda’s birthday I call the photo MAINER OUT WEST

I call the photo MAINER OUT WEST

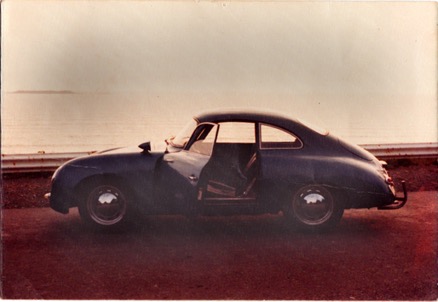

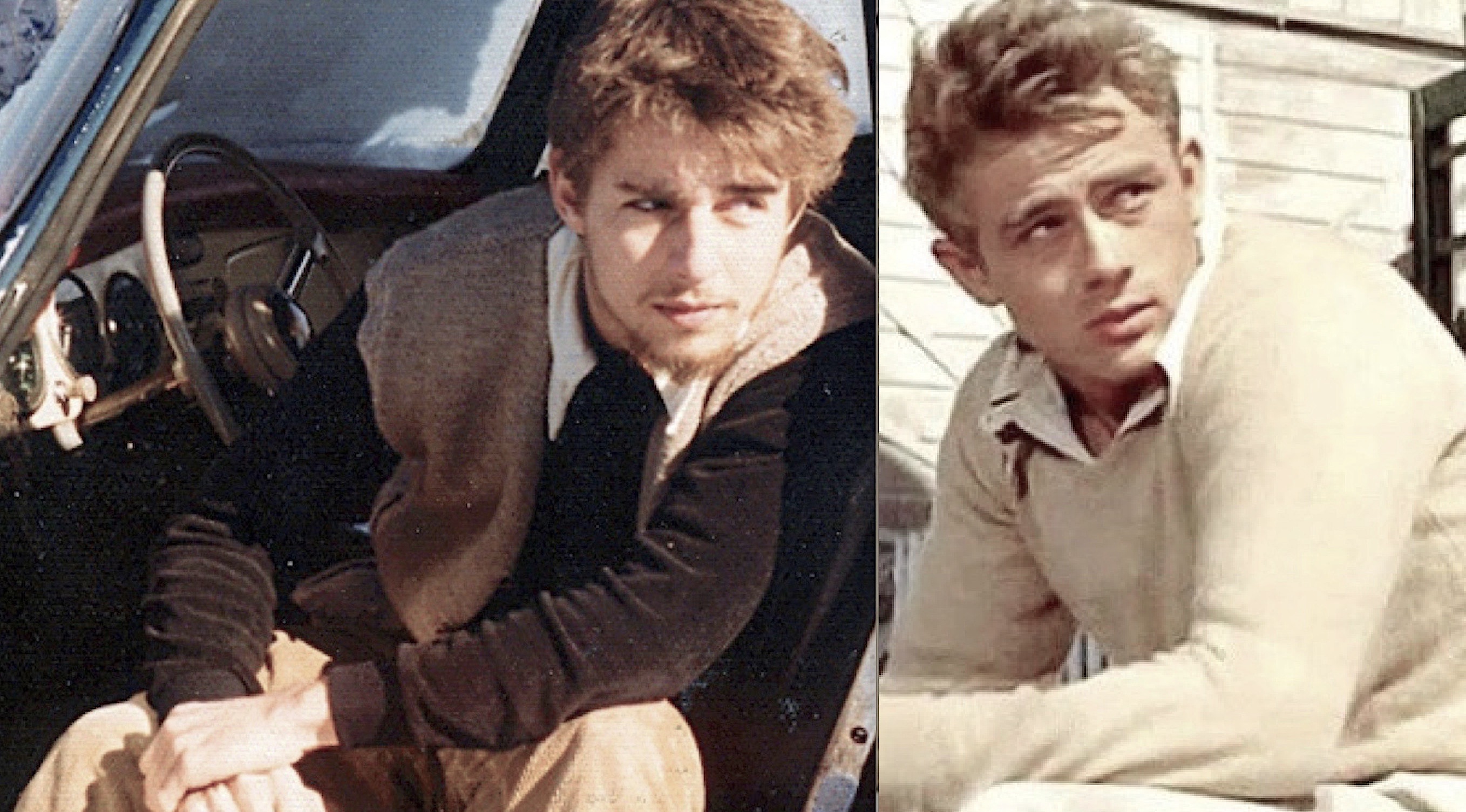

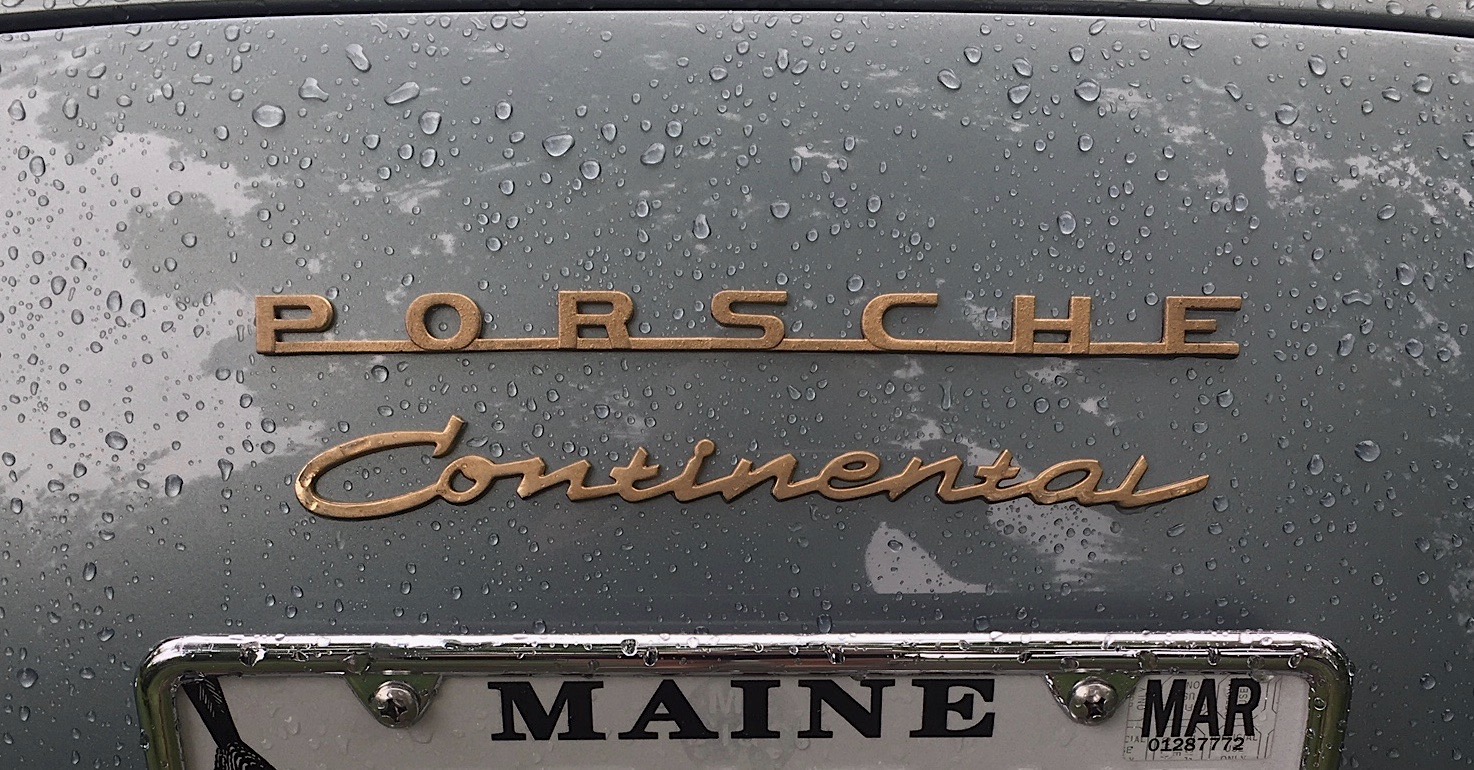

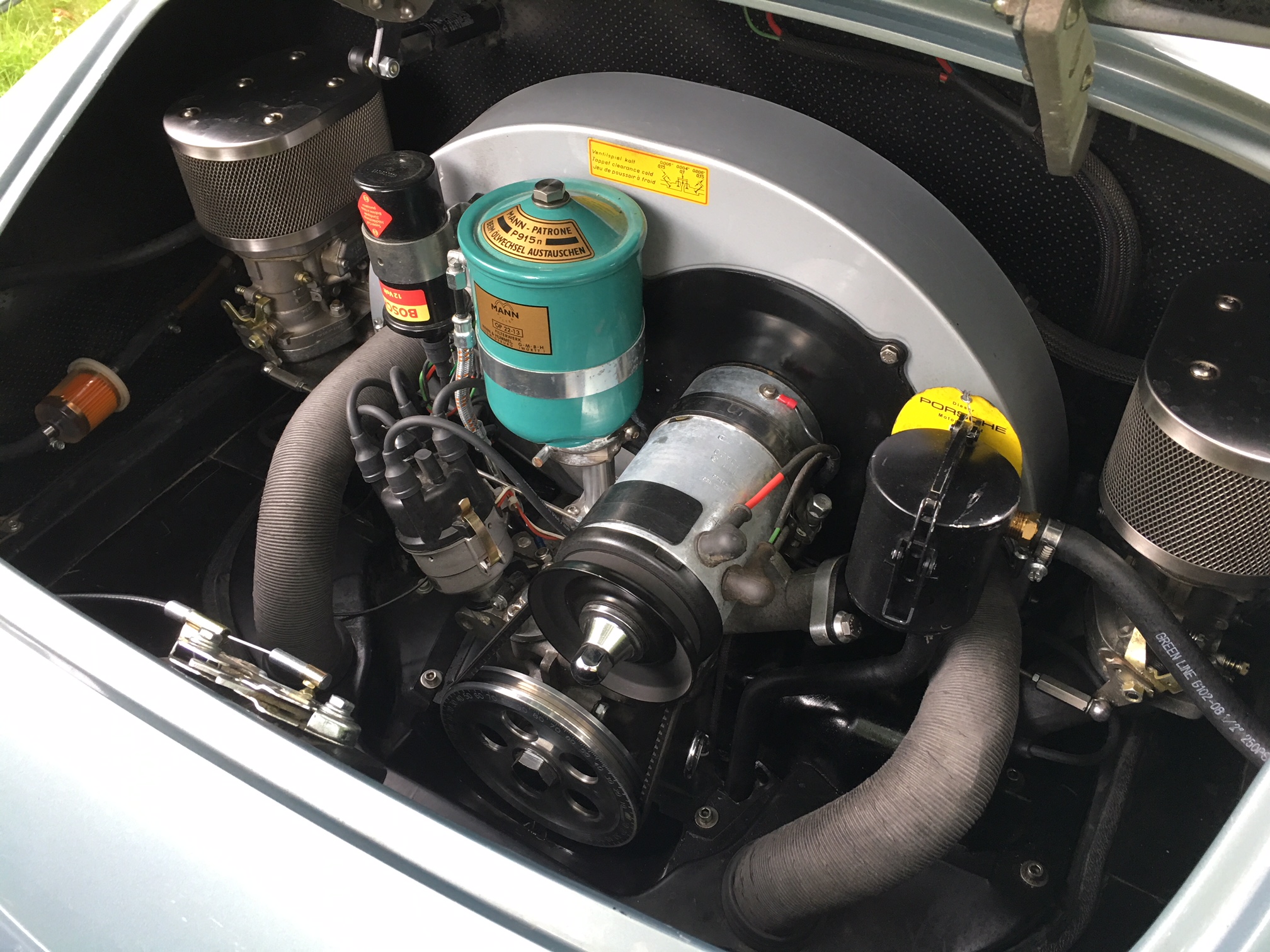

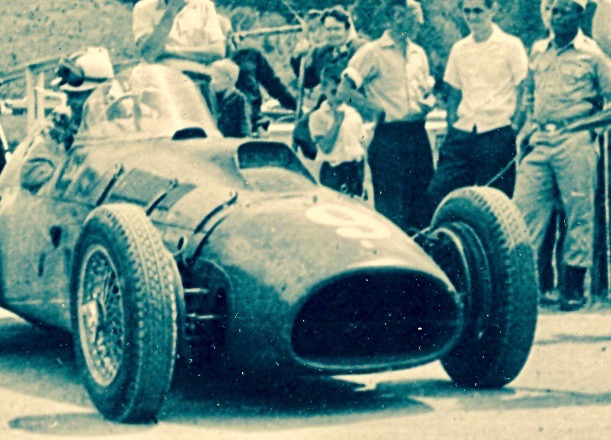

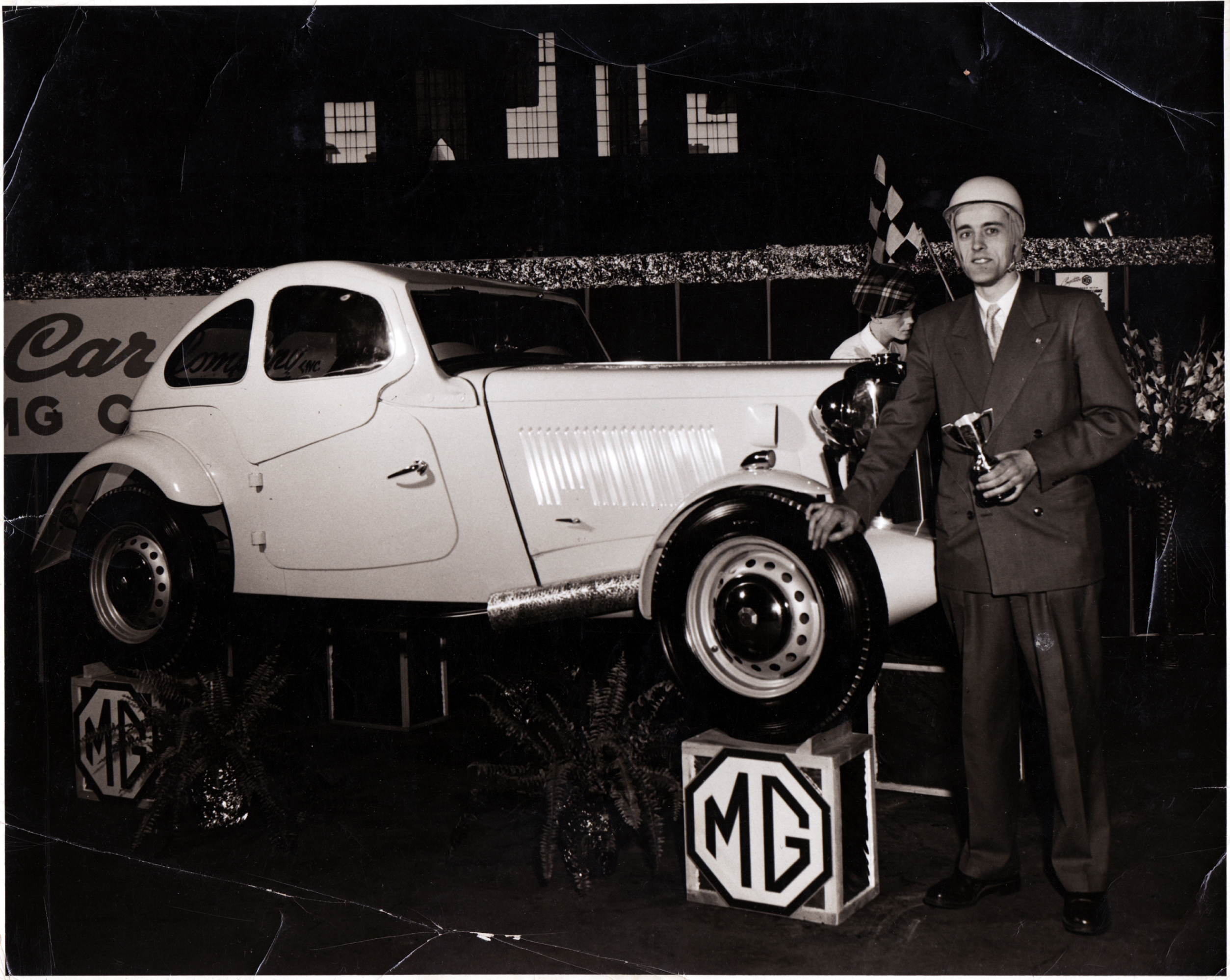

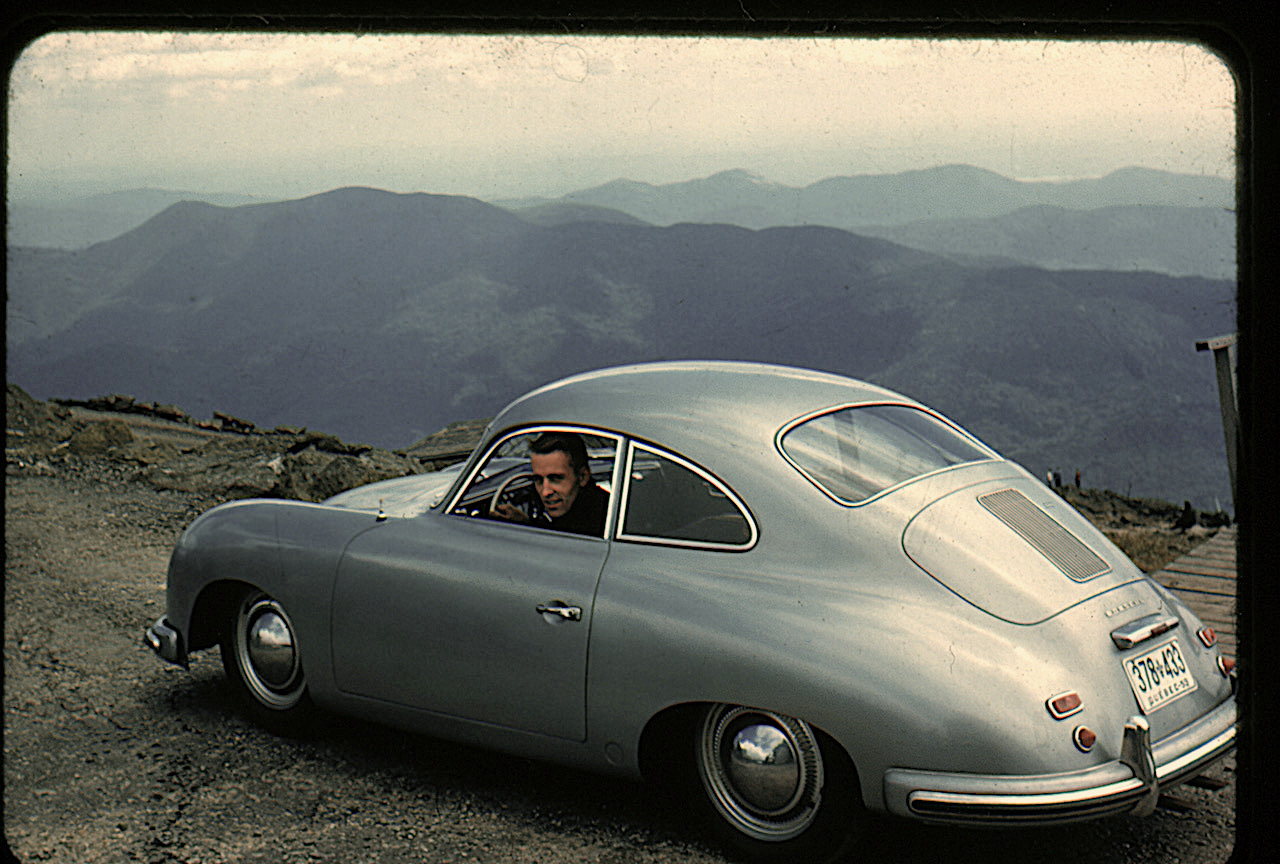

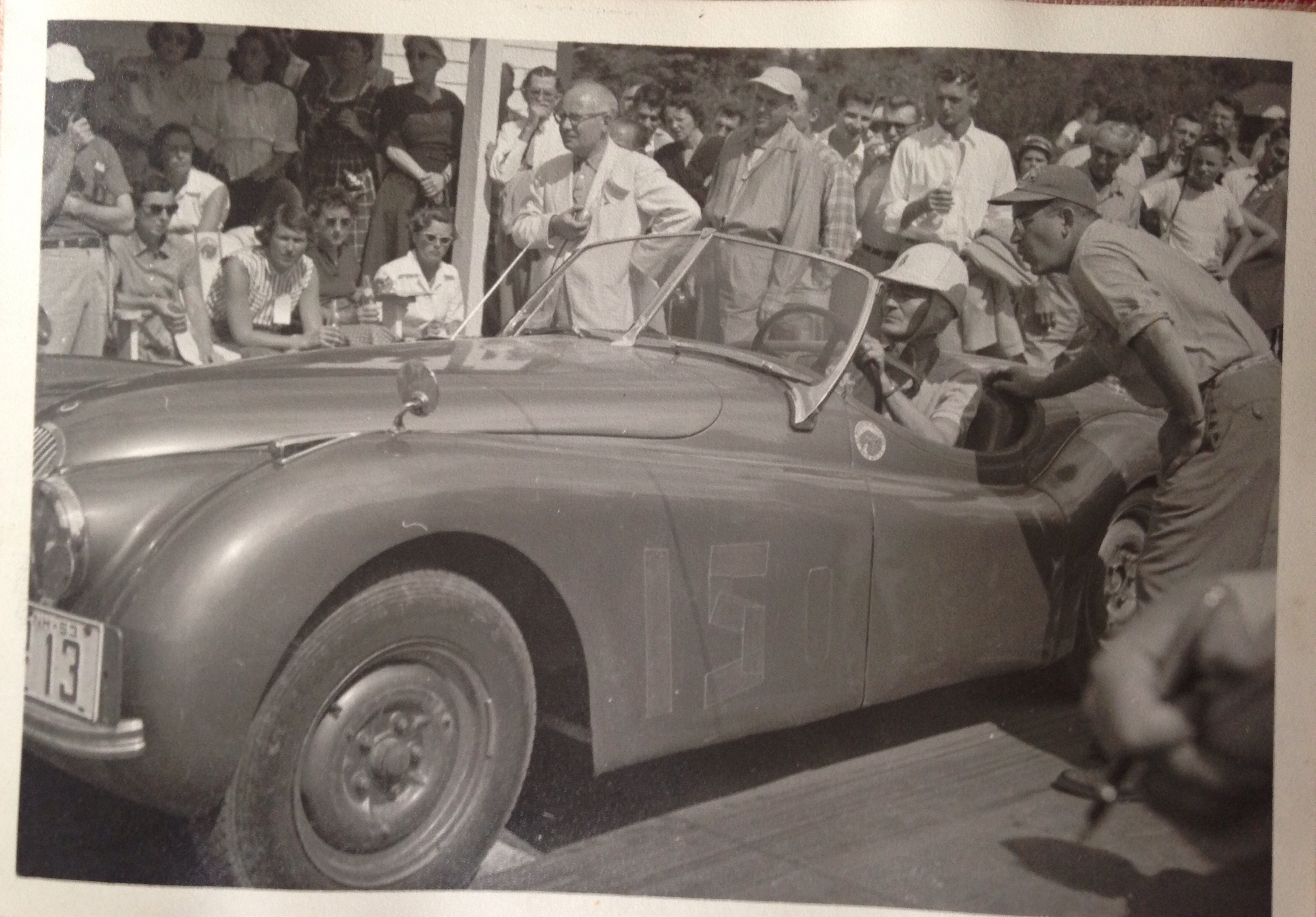

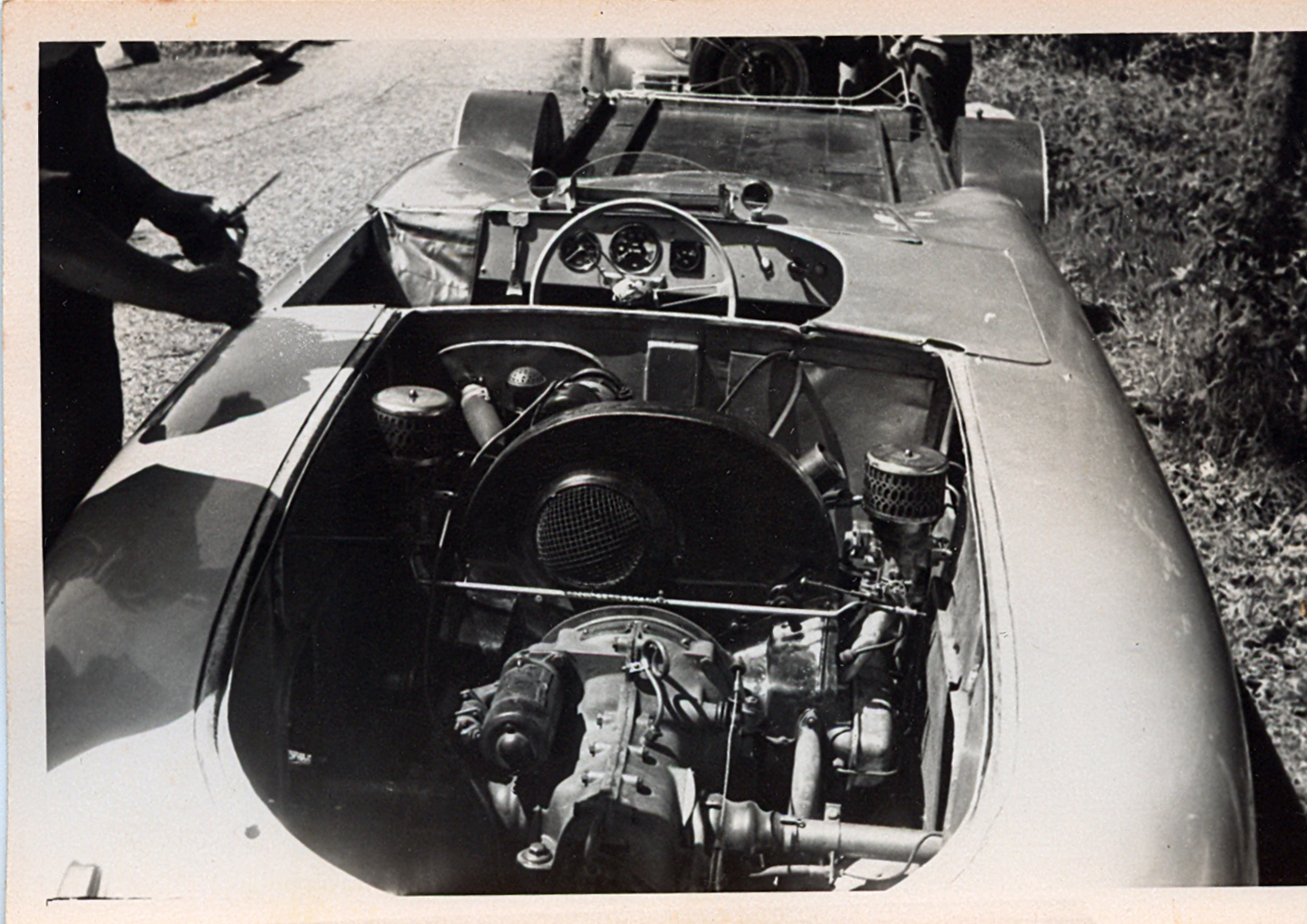

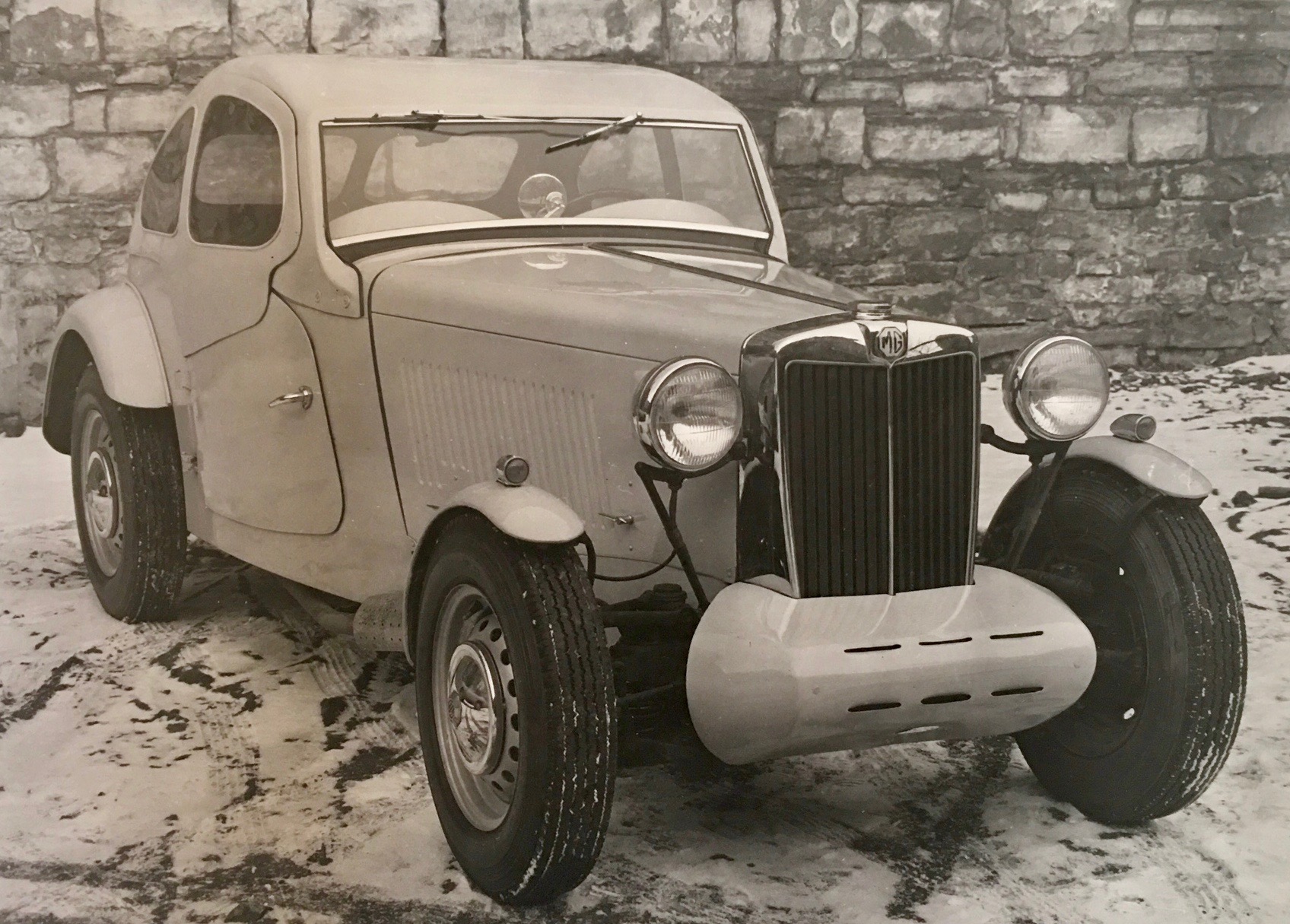

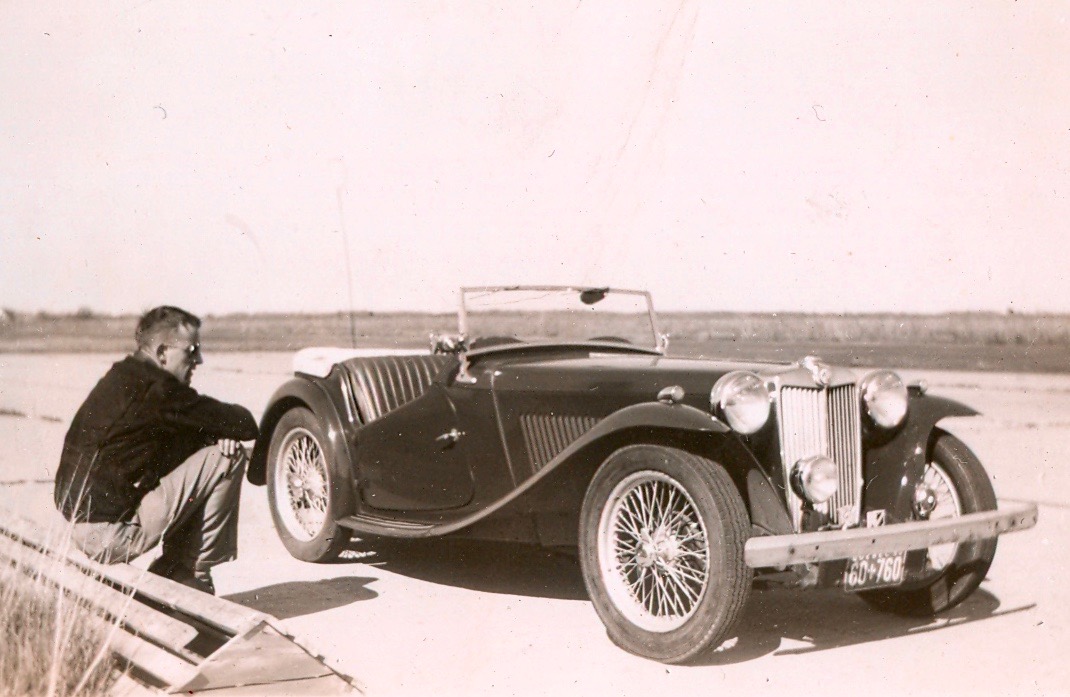

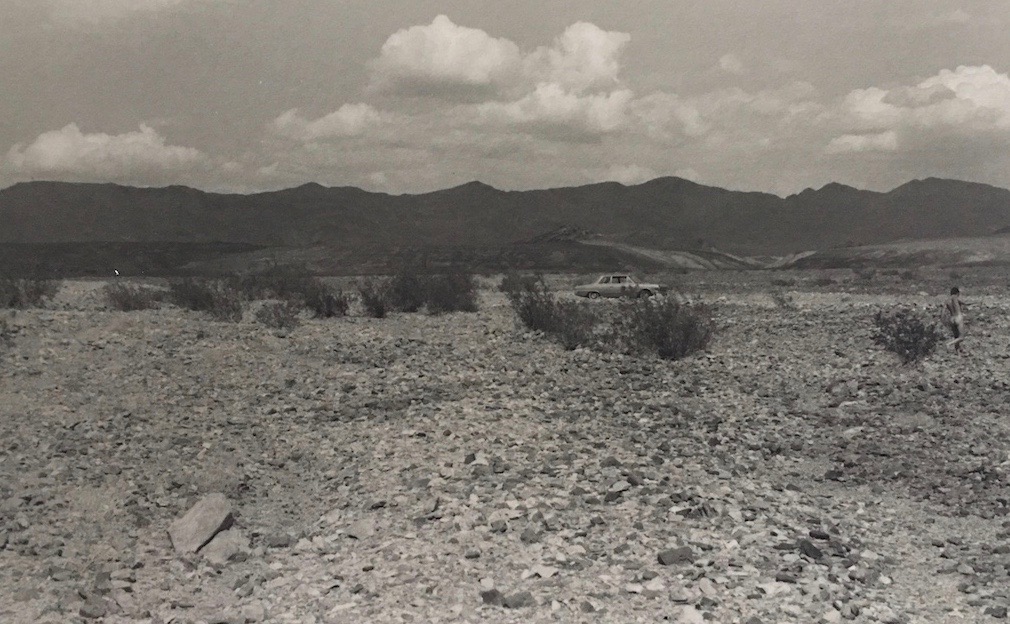

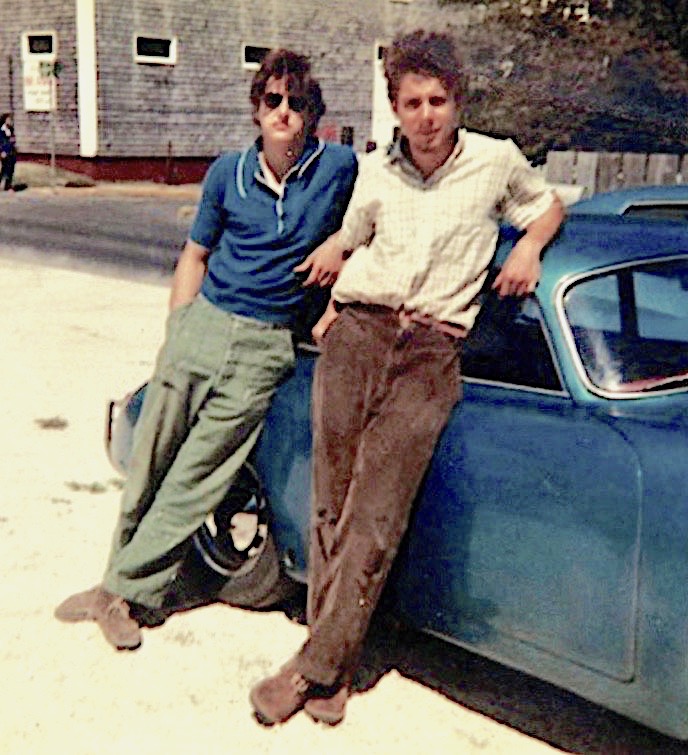

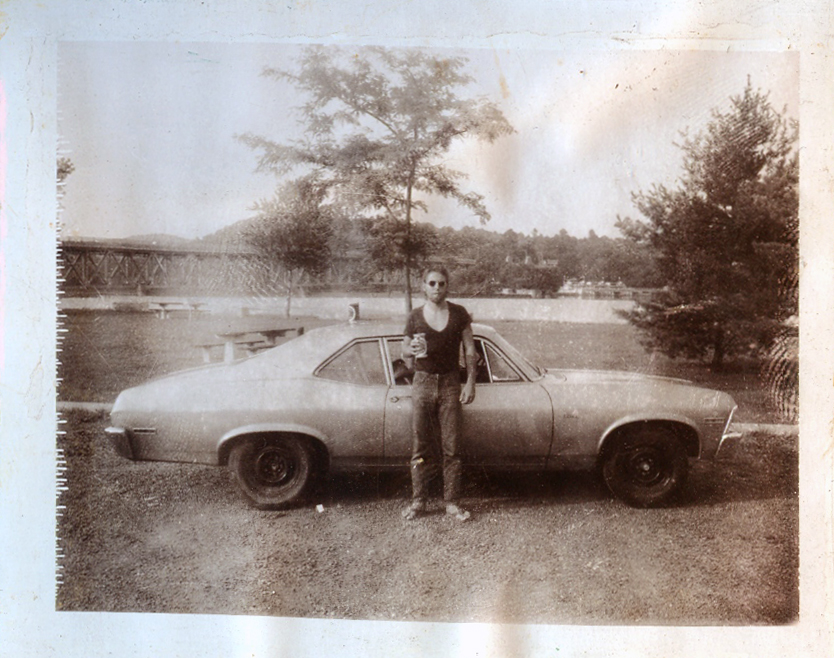

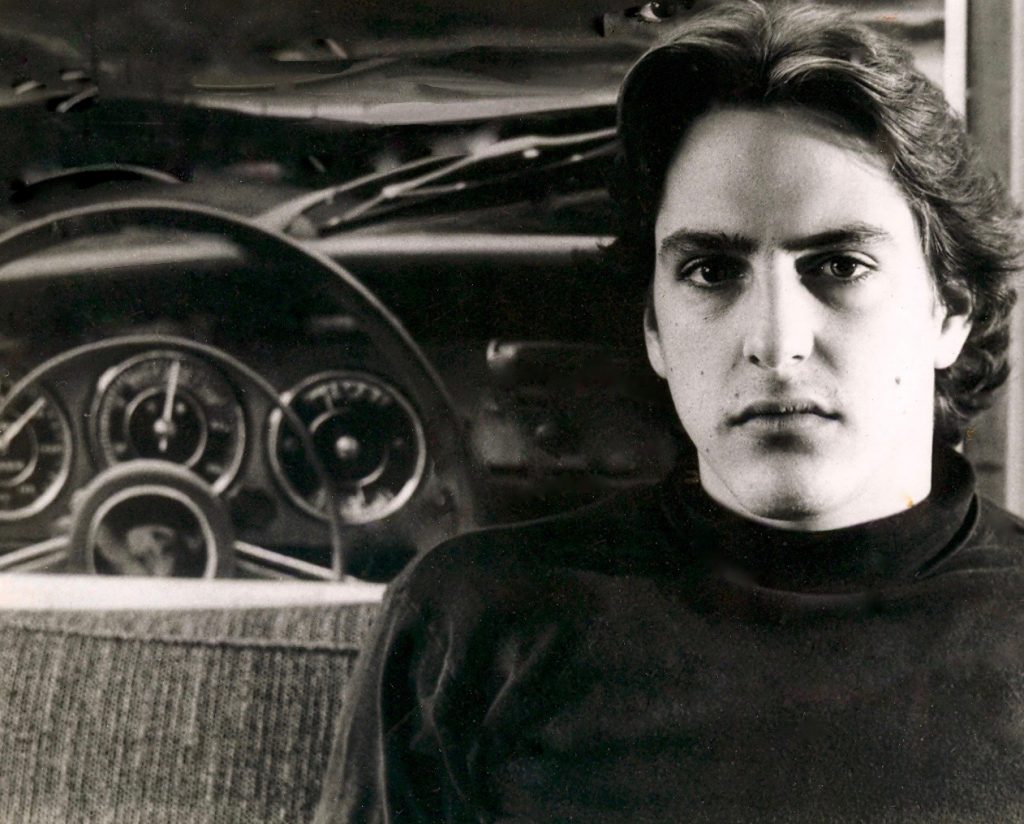

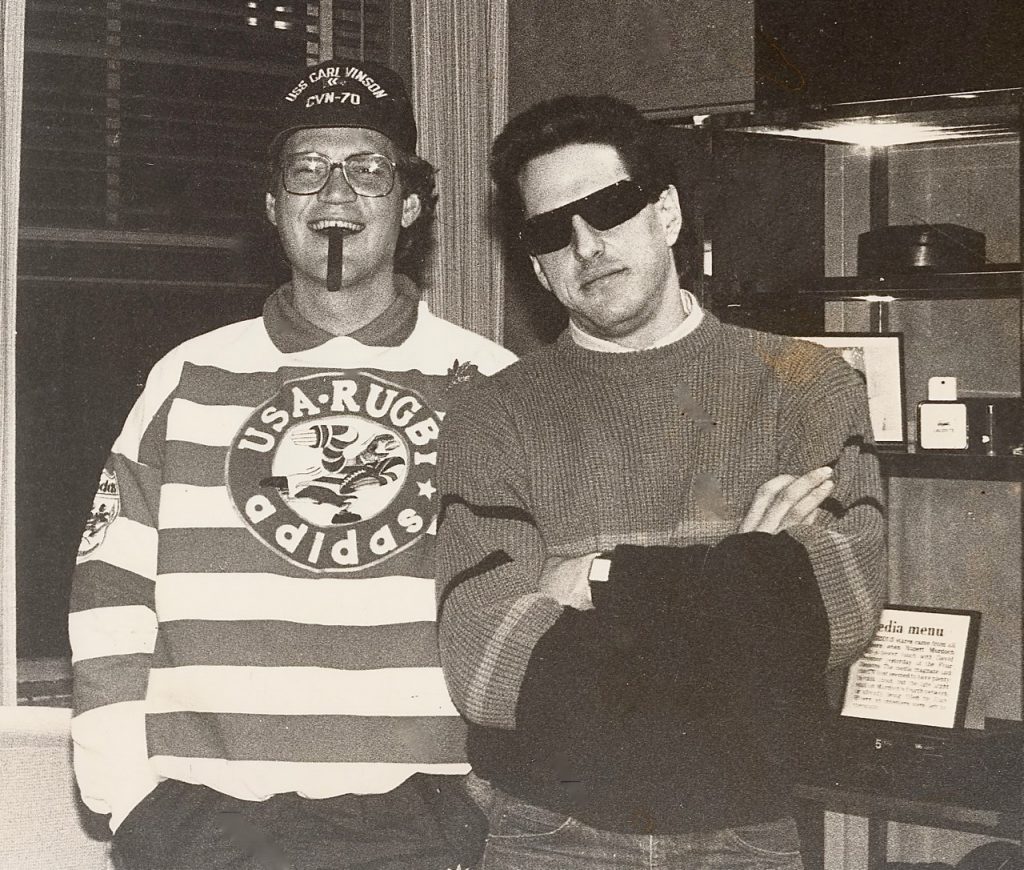

This photo shows the Bursch Extractor racing exhaust, which sounded incredible as we tore through city streets, the sound echoing off the brick and cement gauntlet, Kris hanging out of the window, half his body out of the car as he loved to do then, showing off his well-muscled naked torso, screaming at the cute girls, “It’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia,” over and over.

This photo shows the Bursch Extractor racing exhaust, which sounded incredible as we tore through city streets, the sound echoing off the brick and cement gauntlet, Kris hanging out of the window, half his body out of the car as he loved to do then, showing off his well-muscled naked torso, screaming at the cute girls, “It’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia, it’s the Mille Miglia,” over and over.

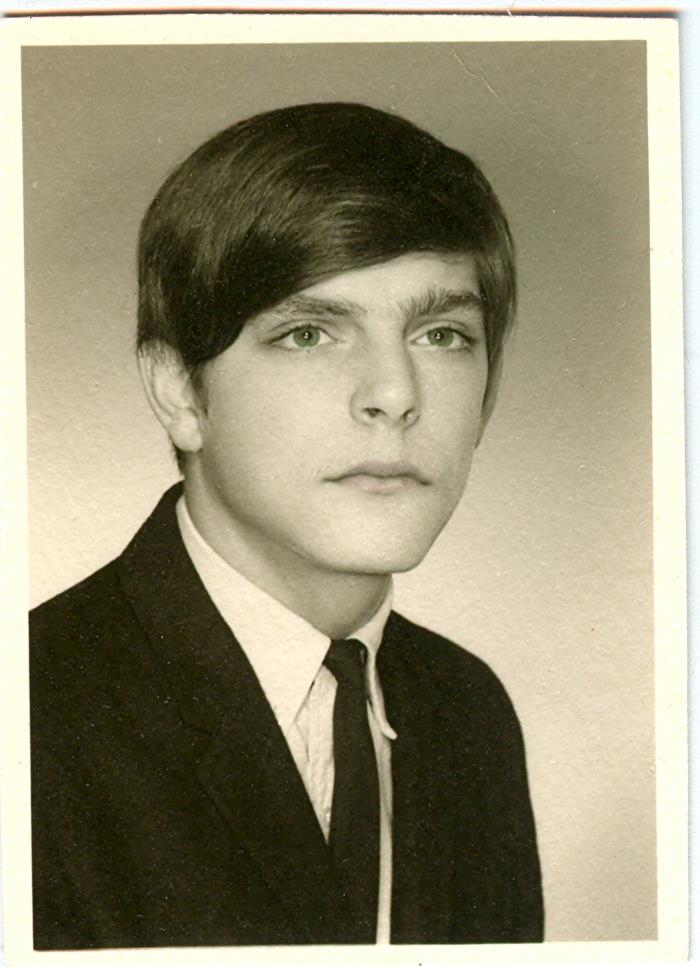

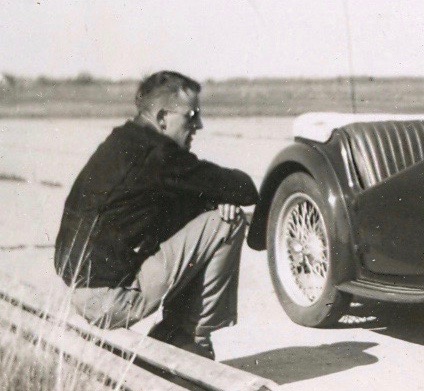

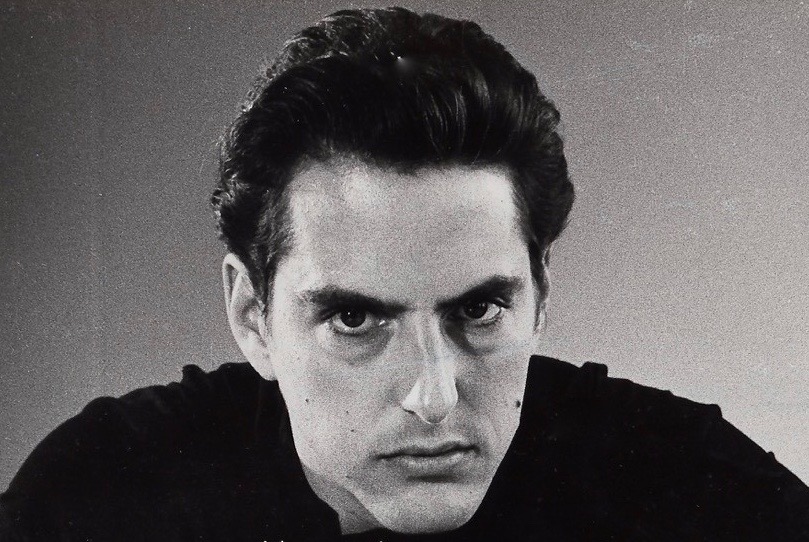

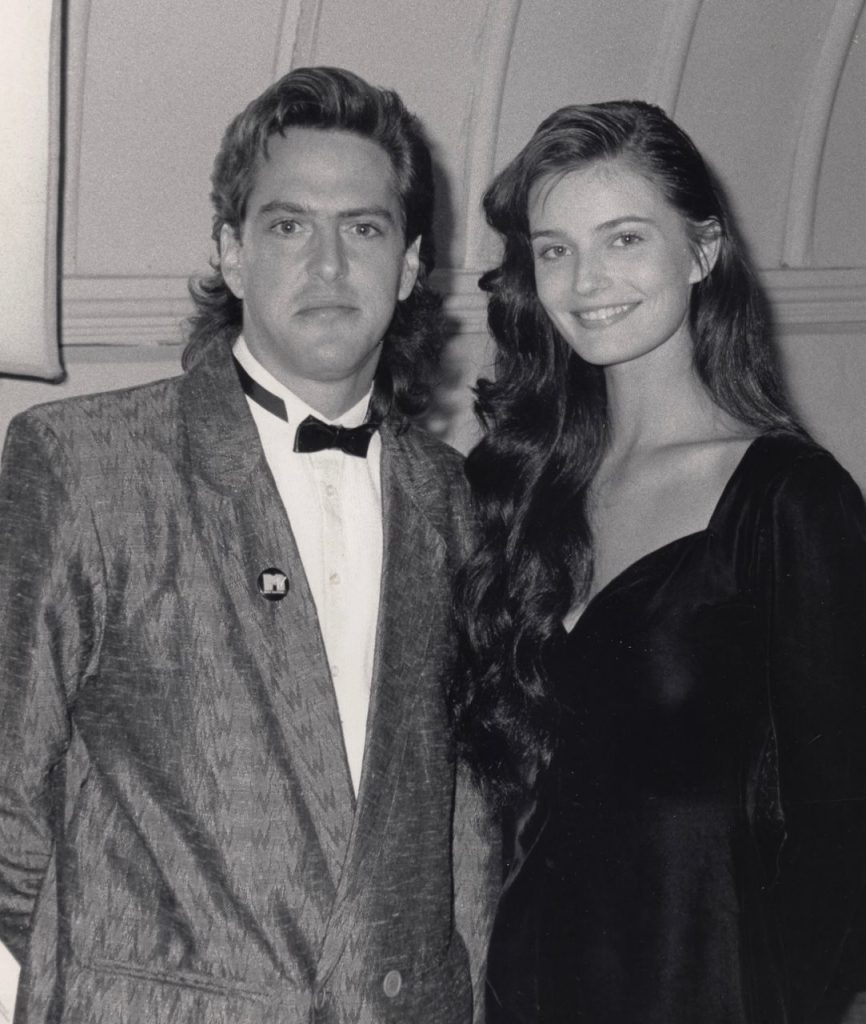

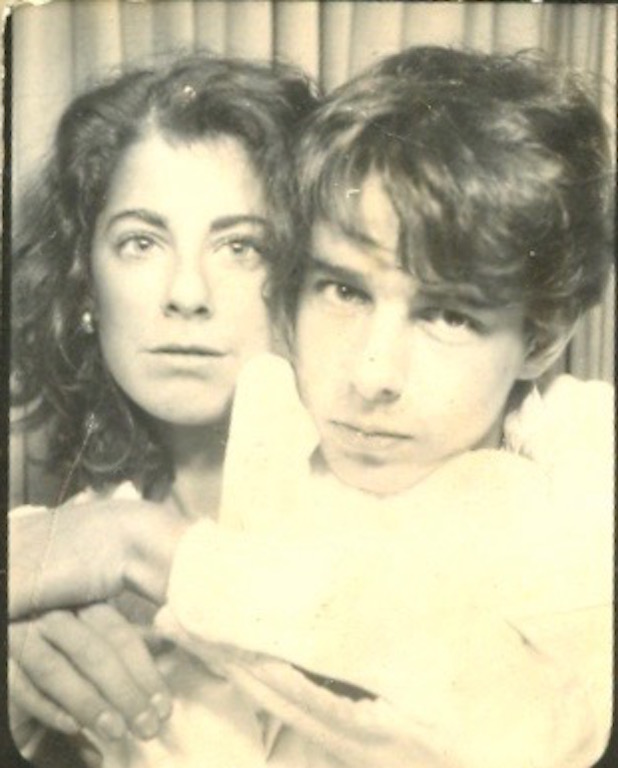

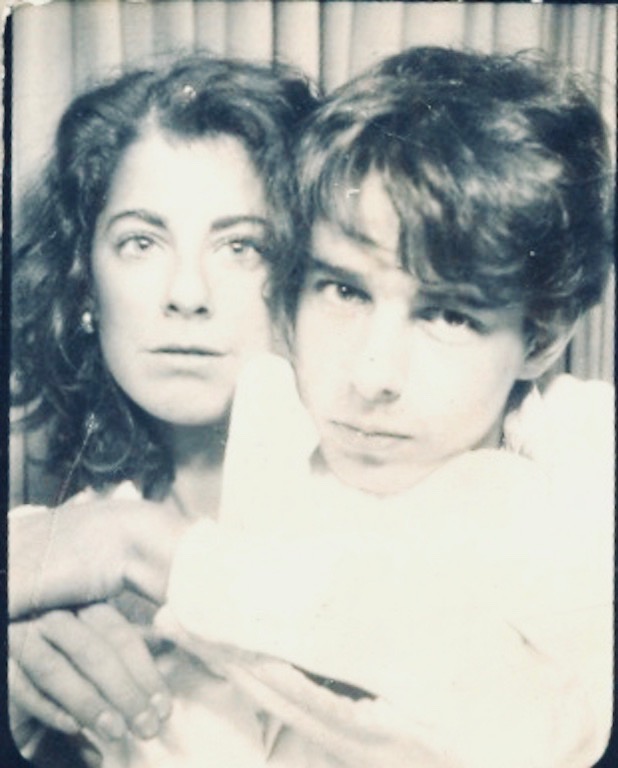

Taken in one of those photo booths that were in train and bus stations. Providence, January, 1974, I was 17 by less than a few weeks, Andrea Shapiro (Andi Shapiro) was 21. Think of that!

Taken in one of those photo booths that were in train and bus stations. Providence, January, 1974, I was 17 by less than a few weeks, Andrea Shapiro (Andi Shapiro) was 21. Think of that!

The Maine Coast has always been my favorite place on Earth, and to live here is a daily joy. I simply like everything about it, and the true Mainers exemplify what I admire in people as well, although I’ve always preferred animals and nature to most people. After all, I’m misanthropic, melancholic, quite agoraphobic now, as well as germaphobic and reclusive—a hermit who loves only one woman and one cat—a Maine Coon of course. Perfect combination of attributes for mid-coast Maine.

The Maine Coast has always been my favorite place on Earth, and to live here is a daily joy. I simply like everything about it, and the true Mainers exemplify what I admire in people as well, although I’ve always preferred animals and nature to most people. After all, I’m misanthropic, melancholic, quite agoraphobic now, as well as germaphobic and reclusive—a hermit who loves only one woman and one cat—a Maine Coon of course. Perfect combination of attributes for mid-coast Maine.

My godmother’s porch in Gorham, with parents and my godmother in cast. I loved those field stone steps and rebuilt them for free during the 1980s.

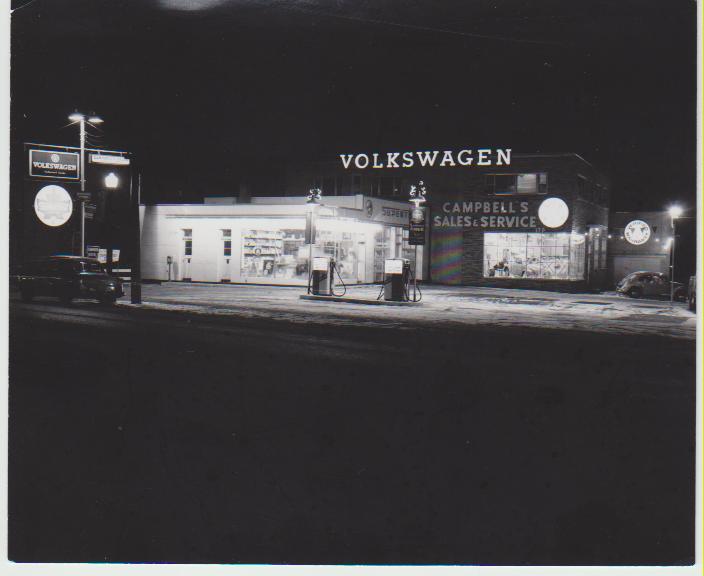

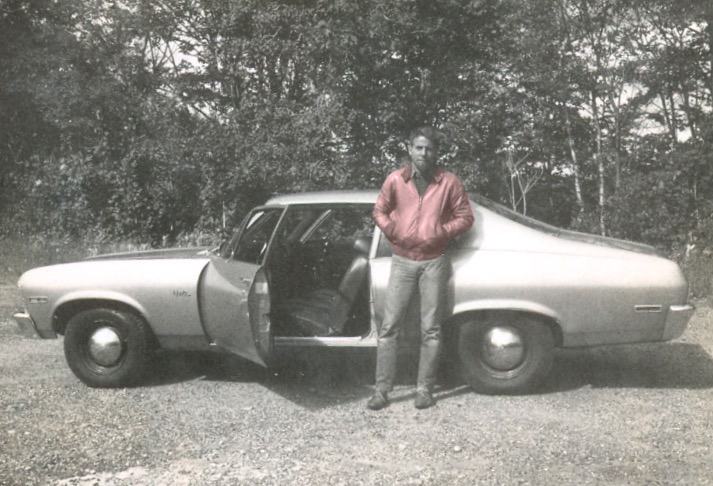

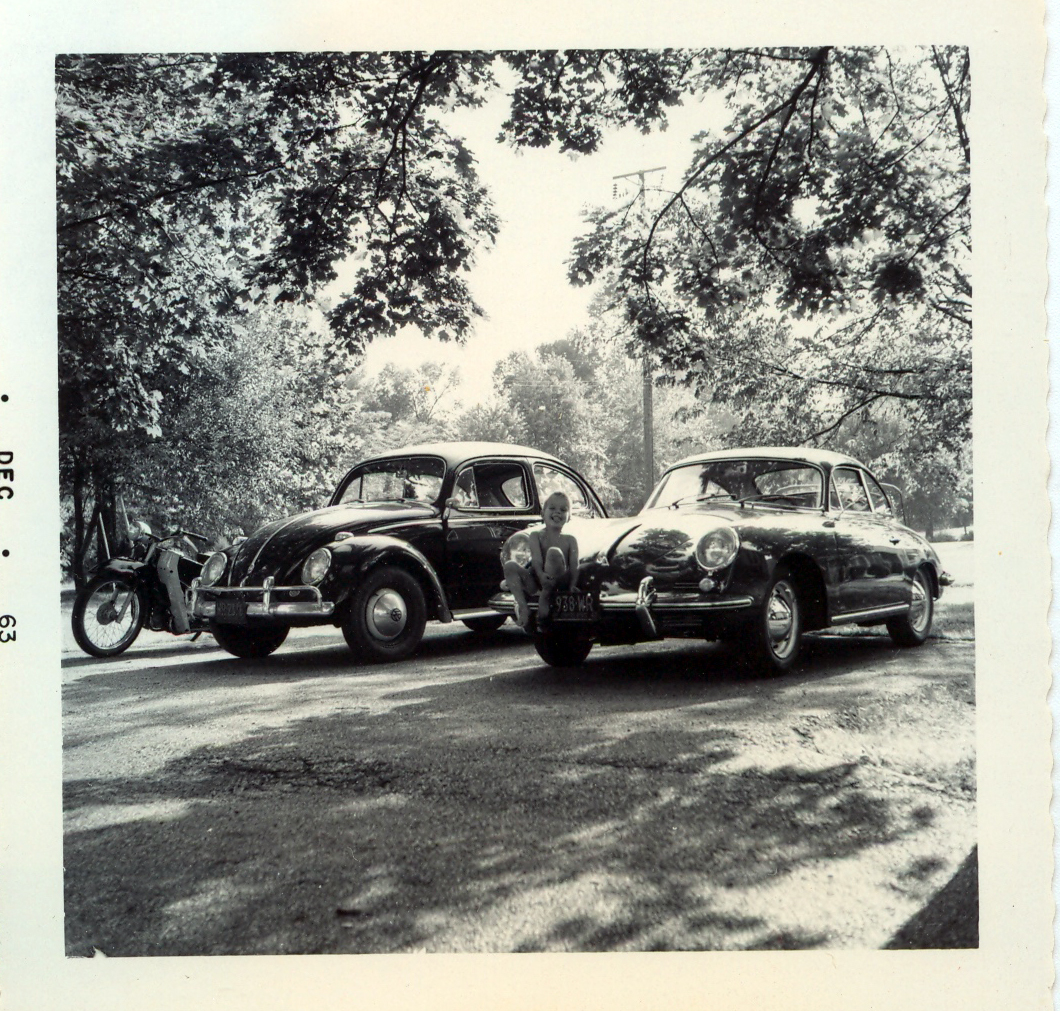

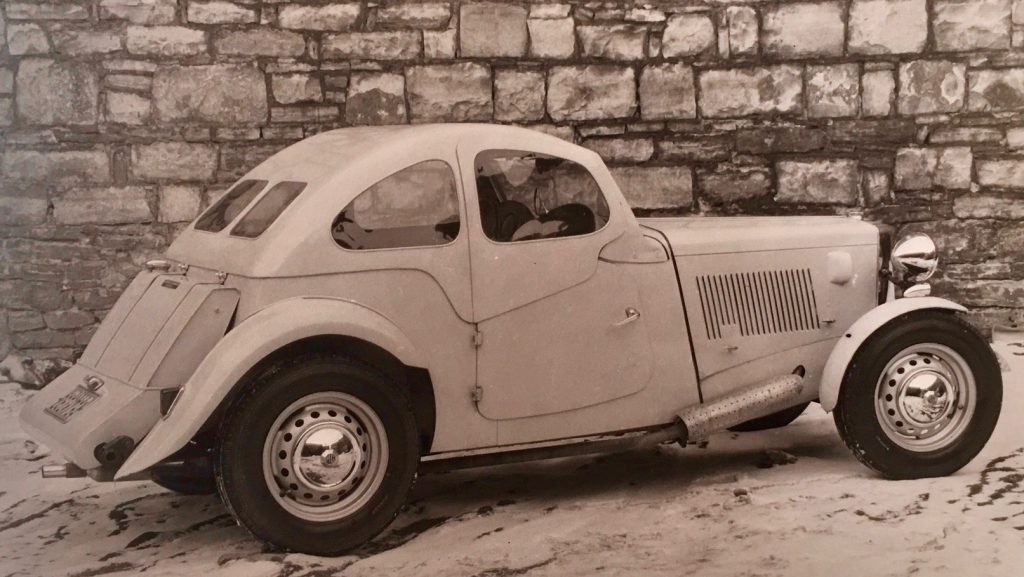

My godmother’s porch in Gorham, with parents and my godmother in cast. I loved those field stone steps and rebuilt them for free during the 1980s. The house that began my obsession with Victorians and large houses in general. Hal Stowell and his Volkswagen the summer of 1972 when we drove from Massachusetts to Prince Edward Island to catch the total eclipse of the sun. That is another entire road trip story, which began many of the rituals that followed through the years. I must have been 15.

The house that began my obsession with Victorians and large houses in general. Hal Stowell and his Volkswagen the summer of 1972 when we drove from Massachusetts to Prince Edward Island to catch the total eclipse of the sun. That is another entire road trip story, which began many of the rituals that followed through the years. I must have been 15.

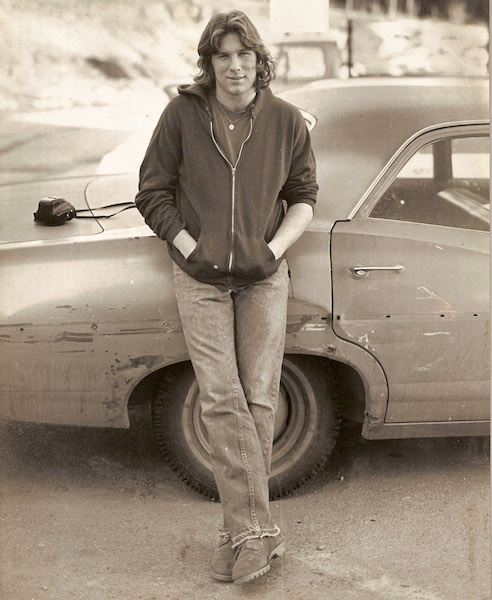

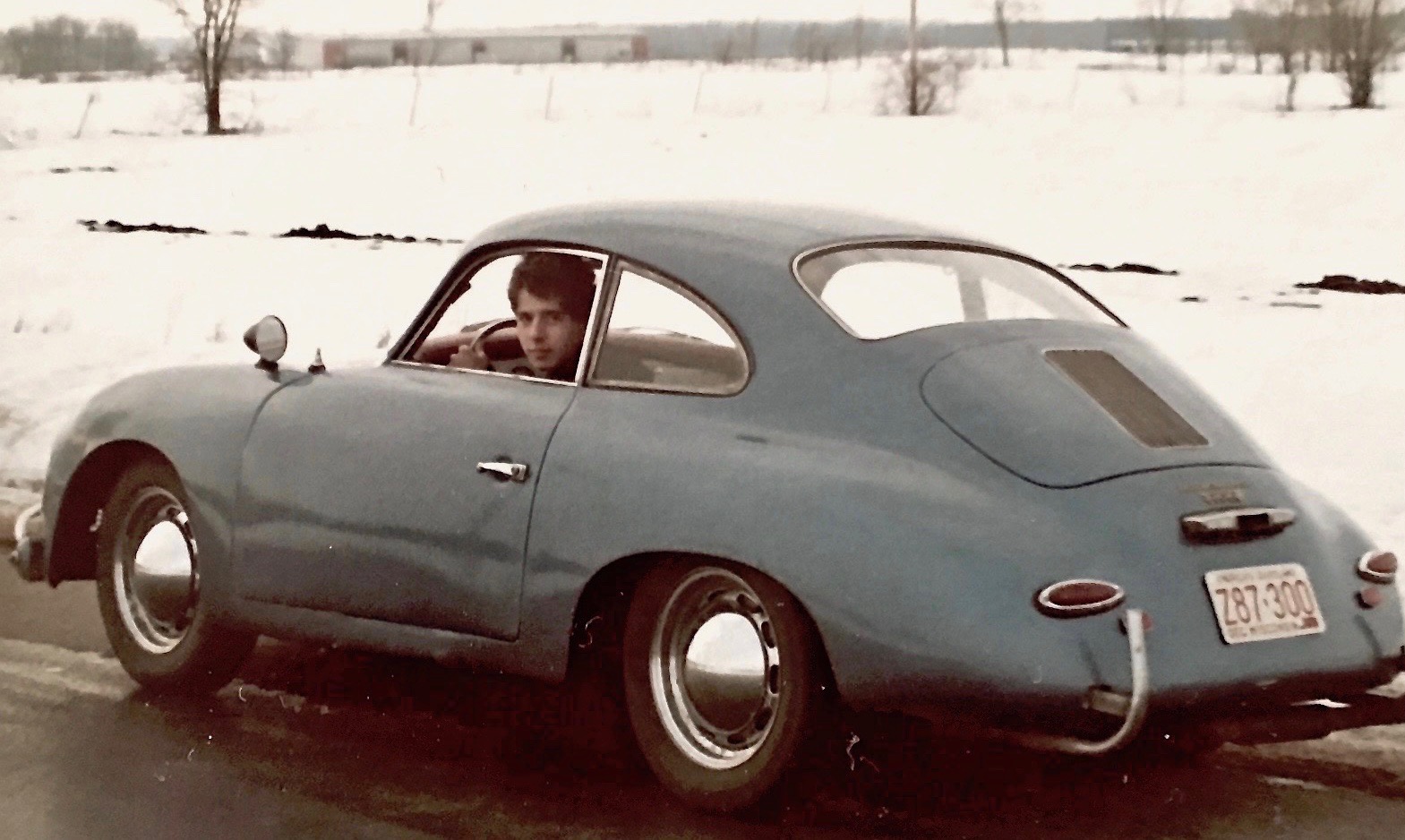

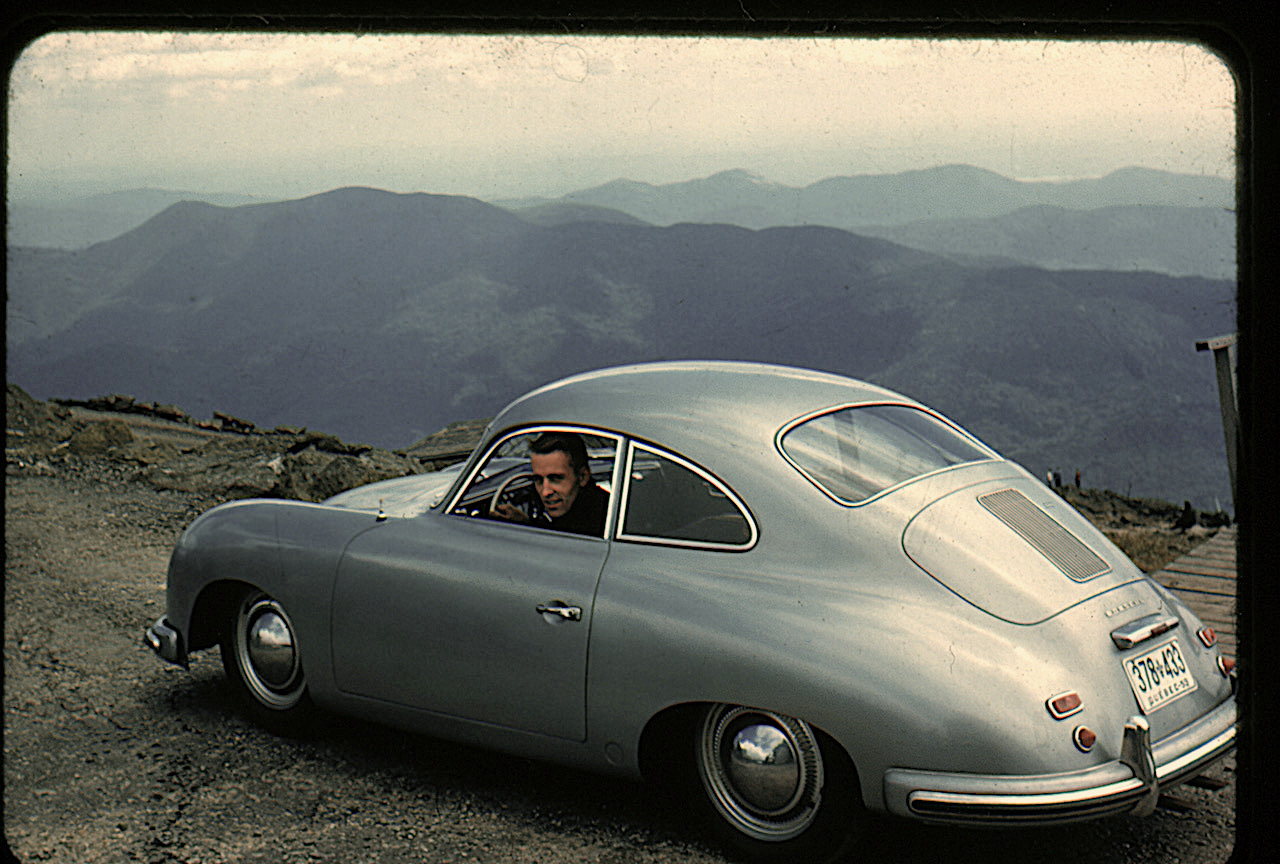

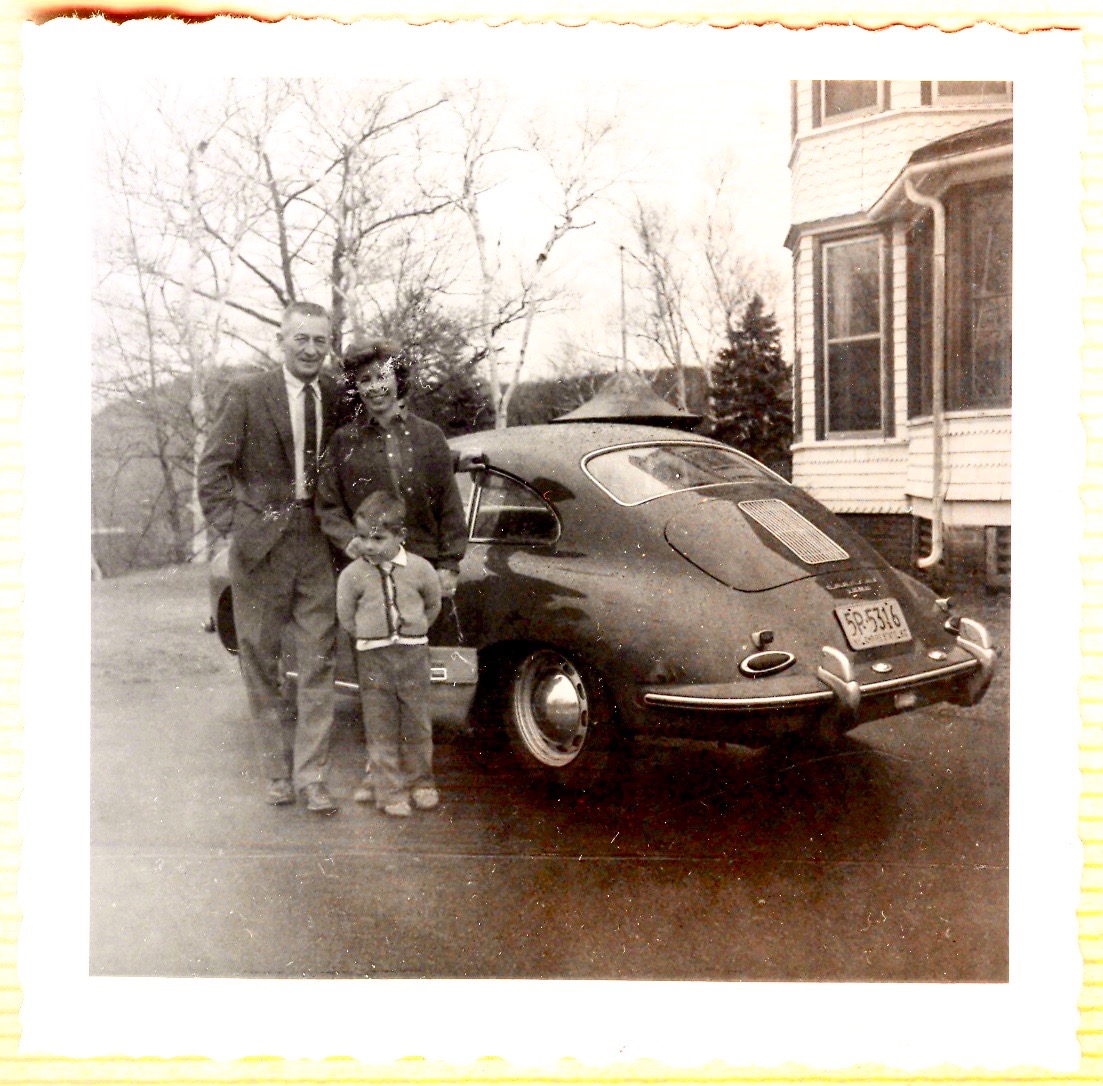

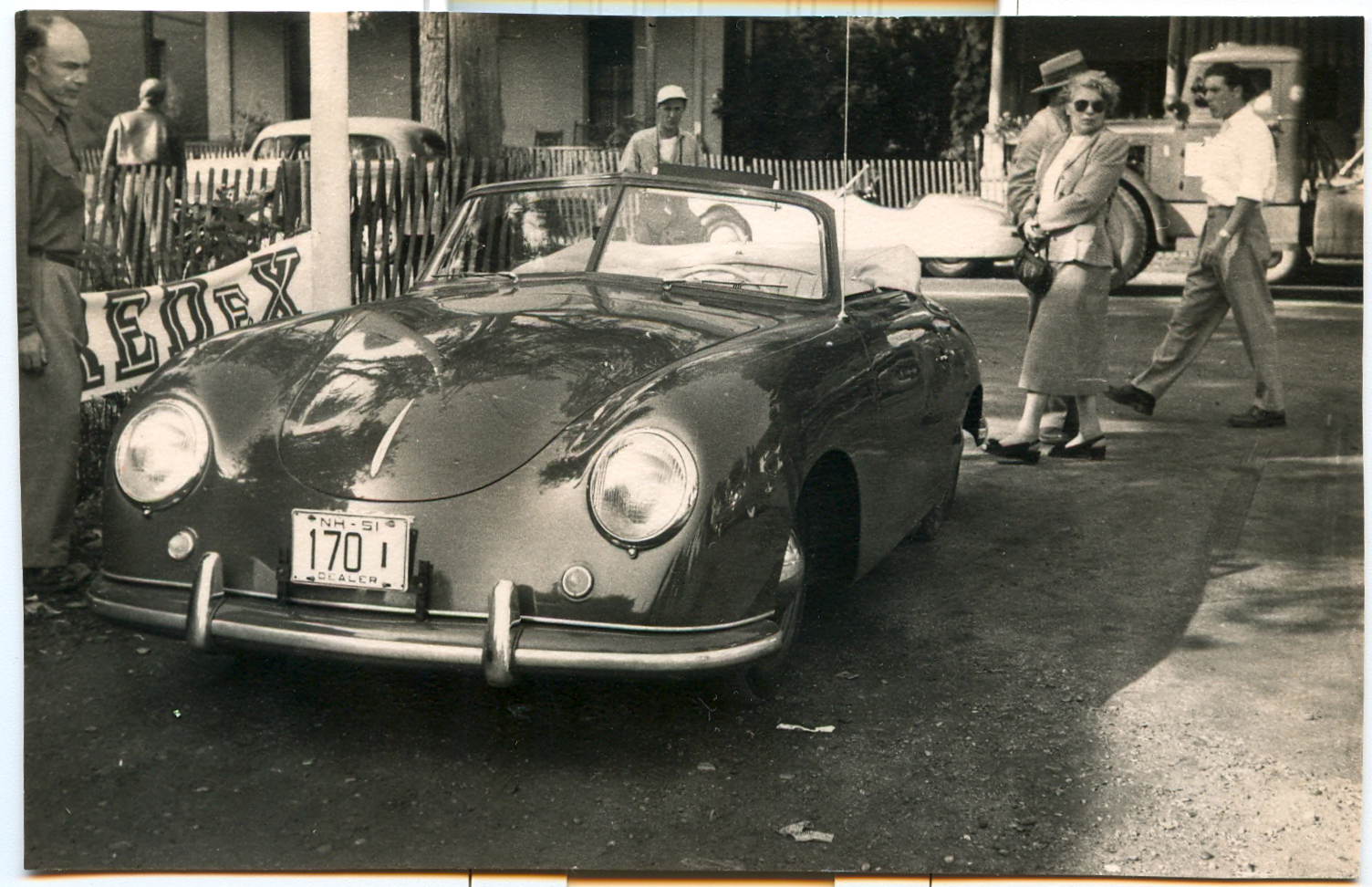

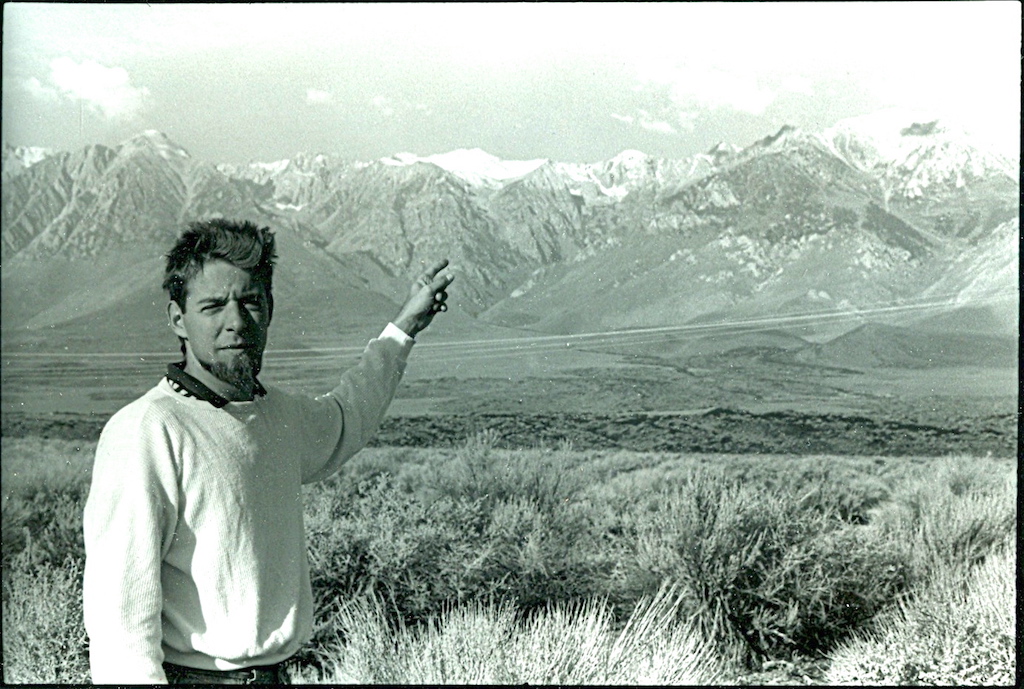

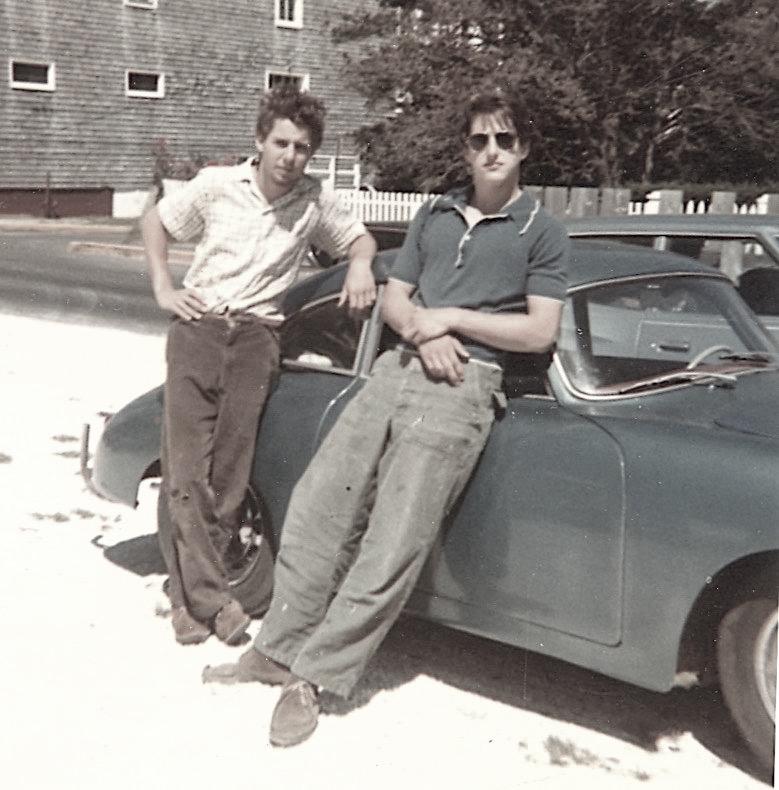

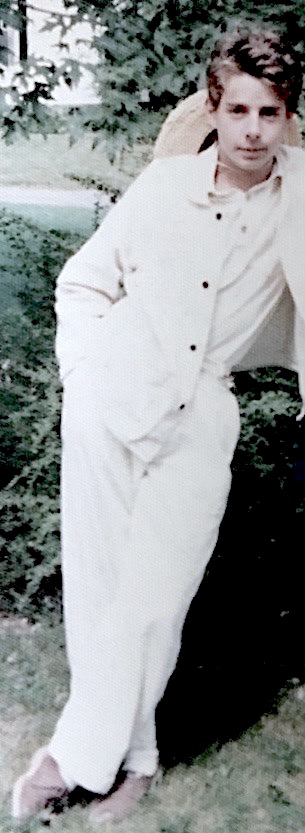

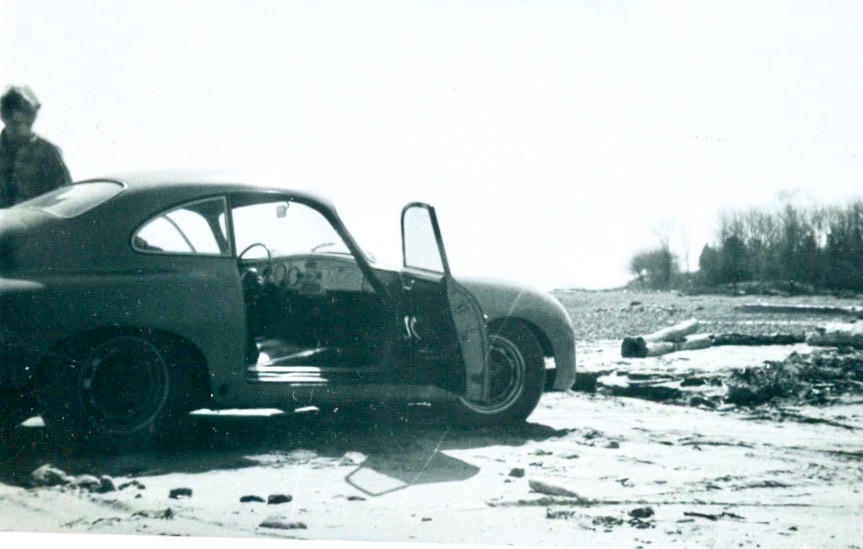

Photo was taken in the farm fields of Wisconsin, January, 1975. The temperature? Only a tad under 5, but I thought my polyester pearl-snap suit had quite the look. I only look cold because of the wind (always raging across those flats) and the fact that the 356 had no functioning heat at this time. Soon enough I closed some of the large holes in the heat exchangers with tin and duct tape. Better? Only very slightly, but it felt glorious, even if it was the kind of heat your favorite pet blows against your chest on a cold afternoon in bed.

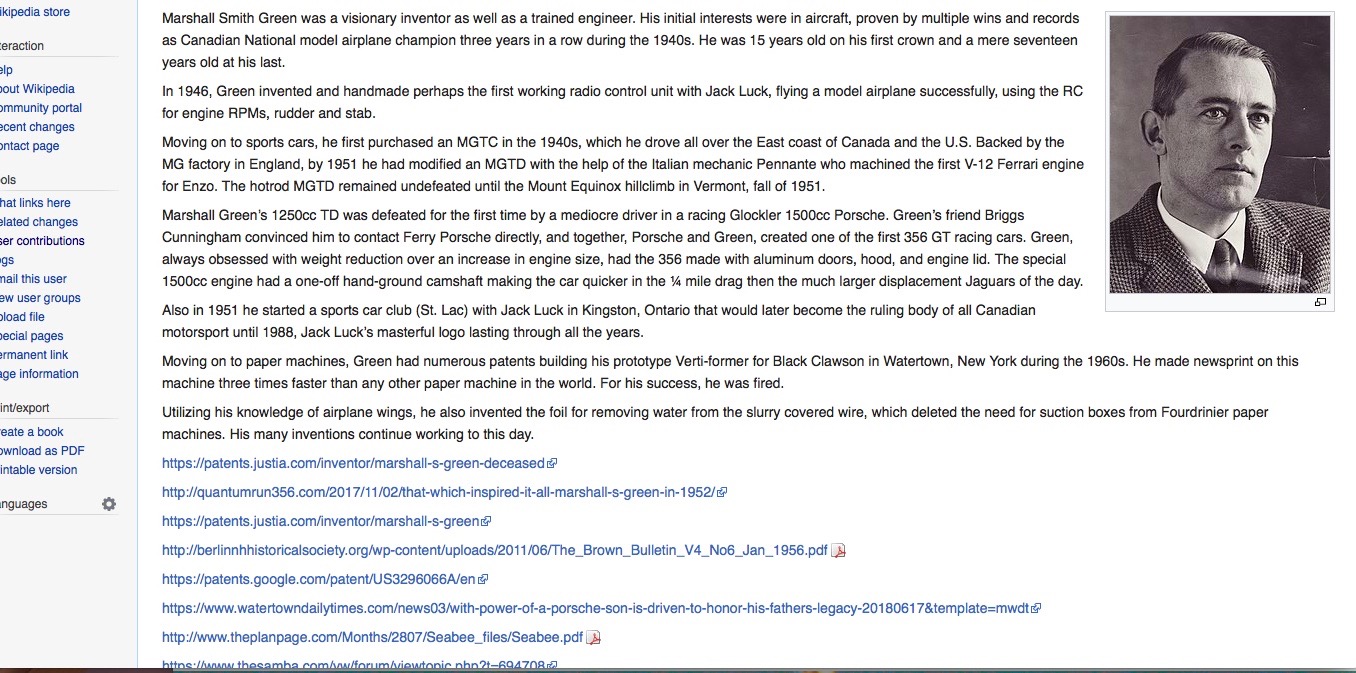

Photo was taken in the farm fields of Wisconsin, January, 1975. The temperature? Only a tad under 5, but I thought my polyester pearl-snap suit had quite the look. I only look cold because of the wind (always raging across those flats) and the fact that the 356 had no functioning heat at this time. Soon enough I closed some of the large holes in the heat exchangers with tin and duct tape. Better? Only very slightly, but it felt glorious, even if it was the kind of heat your favorite pet blows against your chest on a cold afternoon in bed.