A black preacher, mildly senile at 84, escaped from a nursing home in Maryland and drove the car north, still wearing his pajamas, crashing the vehicle into a guard rail on Interstate 91 in Saint Johnsbury, Vermont. The car was collected by a garage owner known as the Wizard and towed to Railroad Street Mobil while the escapee was returned to the home. Had his desire been Canada, or to forestall the clamp of approaching death, no one will ever know.

A week later I received a phone call from the Wizard, a nickname earned through his remarkable abilities with machinery. “Eric, would you know anyone who might need a car that doesn’t look so great, but runs perfectly?” He had pulled the main dent out of the body and realigned the front end. “Should run fine for a lot of miles,” he added.

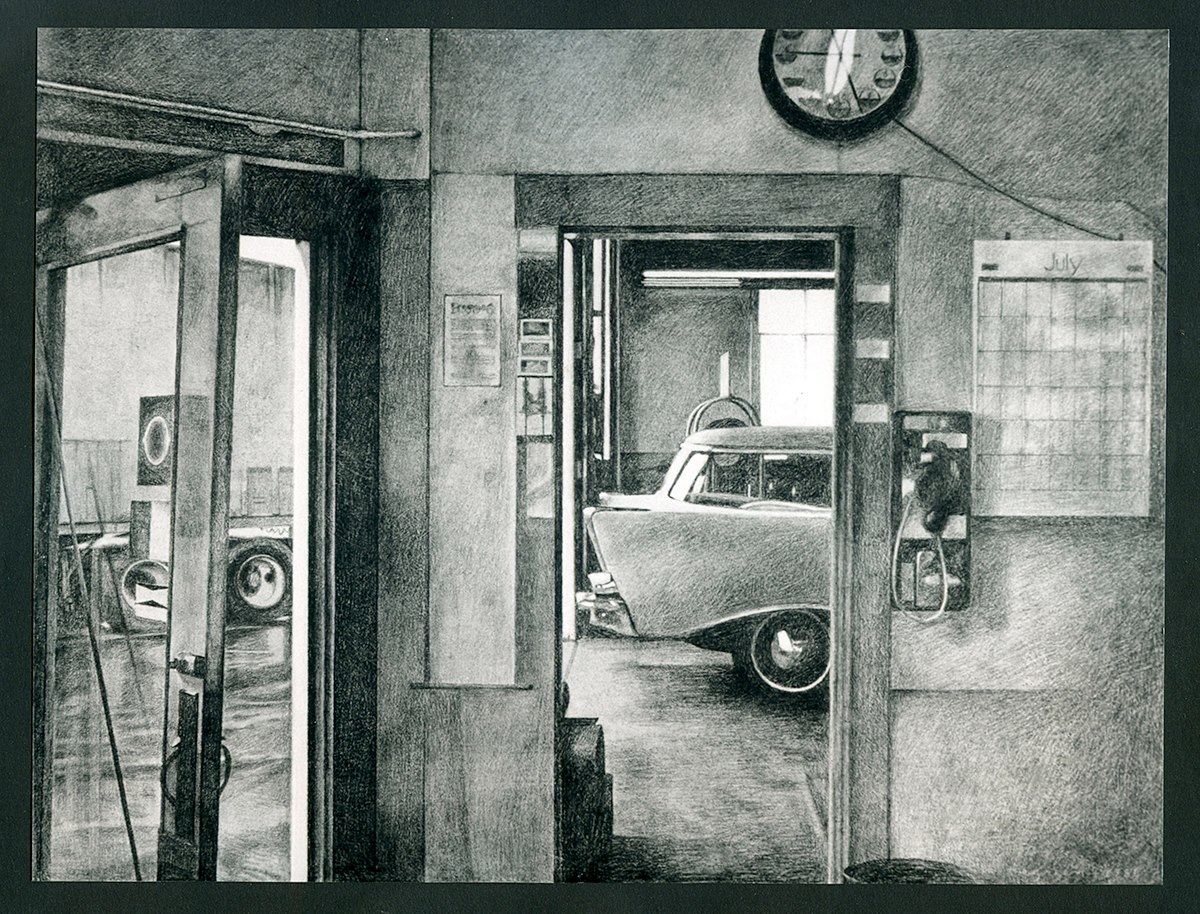

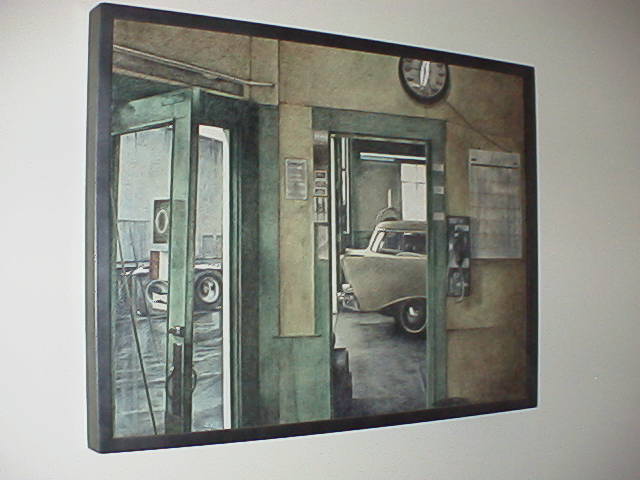

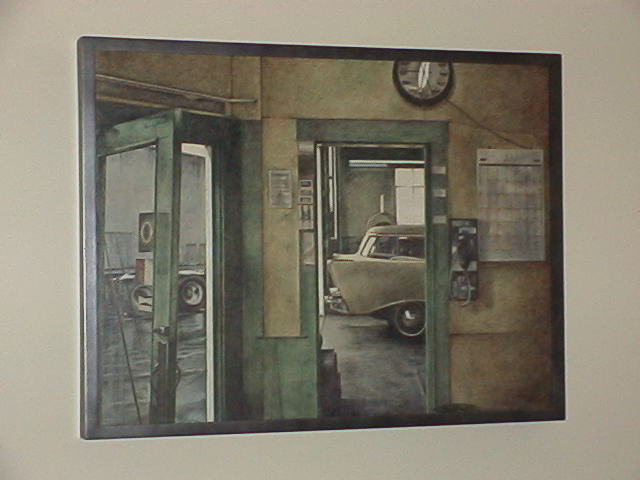

Wizard, grisaille on marble dust panel with acrylic wash, 1986

These photographs just in (July 2016) from the owner of the work, Carlo Connors. Thanks, bud!

No idea it was about to become a legend, the car was a bicentennial Oldsmobile Delta 88 Royale Holiday Coupe, and after my friend Ben paid 200 dollars for it back in 1989, it ran with only one (rather clairvoyant) stutter for an additional 100,000 miles until it exploded into an oily fire one morning in Santa Cruz, the Wizard’s prophecy holding true. Ben left Maine for California that fall in the Preacher—the obvious nickname. I painted a small flowing arrow on the door for good luck and can still see his taillights heading west. Little did I know that afternoon that Ben would not return to his birthplace for the next 26 years.

In 1991, I flew to L. A., met Ben, and after a day’s work with screen and Bondo we closed over an elongated rust hole around the rear window of the Preacher that allowed water into the trunk, changed the engine oil, and began our three-state voyage north. This was a road trip, without air-conditioning, before GPS, no set route, no sleeping in motels, only full of willingness to experience whatever happened. We had been invited to a wedding in Seattle, but that was the only mark on the calendar or map.

Leaving the smog of L. A. behind, we motored toward Death Valley, sweet desert air swirling through the car. It was in Baker that the Preacher showed its clairvoyant side. Baker is one of those places that everyone who has visited seems to dislike. I am no exception. We had stopped to stock up on supplies before our descent into the Valley, finding ridiculous prices on everything everywhere in town, even water. But Baker was a monopoly and knew they had you.

After some grumbling, we paid and exited, only to find a large green puddle under the Preacher. I can attest that replacing a water pump (insanely priced but at least they had one) in 107 degree heat and blazing sunshine is a misery, the tools burning my fingers.

To be rolling again, ice cold beer soothing in hand, evening cooling, desert sunset glowing red at the horizon is the kind of contrast that makes the open road wonderful and memorable. Each moment has a way of being charged by emotion of one kind or another. For me, it was also the first time I wasn’t behind the wheel; my consistent role since 1975 had always been as the driver of ever road run. Ben decided he wanted to helm the entire trip himself, and I knew this was important to him: the road inspires the concept of the hero.

At Zabriske Point we stopped in the 100° darkness and wandered about. Suddenly the entire area was lit in blinding light as if a massive strobe had been switched on from the sky. I was so startled I was knocked to the ground. Looking up I saw the acid green tail of a meteor flash across the heavens.

We continued west through the heart of Death Valley, the sole vehicle, pulling over occasionally to allow the antifreeze to stop boiling. How glad we were to have that new water pump installed! At the deserted visitor center, we washed from a hose off a spigot and experienced another oddity in our ignorance. We were both instantly freezing, actually shivering uncontrollably. We jumped into the Preacher, turned on the heater and attempted to warm up—in 95° dryness. The rapidly evaporating wash water had plummeted our core temperatures dangerously.

As we rose in elevation, the outside air cooled, and once we entered a reasonable sleeping climate, we took a few hours’ rest. During that summer, I was obsessed with my first novel Some Broken Heroes, which I had just finished. I realize now that it was just awful, but at the time I was excited and wanted to live out some off the things my protagonist had done in the book. One of these was buying a cowboy hat in Lone Pine.

Once we reached Route 395, the highway seemed to claim us. No, we didn’t gamble in Reno. We did swim in Mono Lake, by far the most brackish water I’ve ever been in, not to mention being nibbled by myriad tiny shrimp as we gazed at tapered monoliths that could’ve inspired Gaudi. This wonderful place was bizarrely deserted. I think Mainers imagine California to be crowded, but I discovered, at least during that era, how empty parts of it actually were.

After crossing over miles and miles of untouched tundra, we motored into Alturas, which would become the hometown of one of my later fictional characters. There was a lumbering hotel out of another century, a classic barber shop across the street where Ben got a haircut, the whole place feeling like a Western movie from the 50s in early Technicolor. A bit farther up the road, not even sure why, we stopped at a roadside jumble store run by two lesbians. When I bought a blanket, they told us about a secret hot springs stream over the Oregon border.

I still dream about that stretch of road. It ran through an antelope reserve, a simple paved swath without shoulders ambling through empty tufted grasslands. The only vehicle we saw in over an hour was a ramshackle pickup driven by a weathered Native who waved calmly in passing. One antelope, skittish until we slowed to a crawl, actually leapt across our path as soft clouds meandered in the distance.

We found the secret place, and just as described, incomprehensibly hot water flowed in and out of bubbling pools in the middle of an enormous flat field of rough grass.

Strange things happen on a road trip. I called Ben yesterday and asked him if I could relay this one. “Why not?” he said. “It’s part of the story. It shows how the stress of travel can build up over time.”

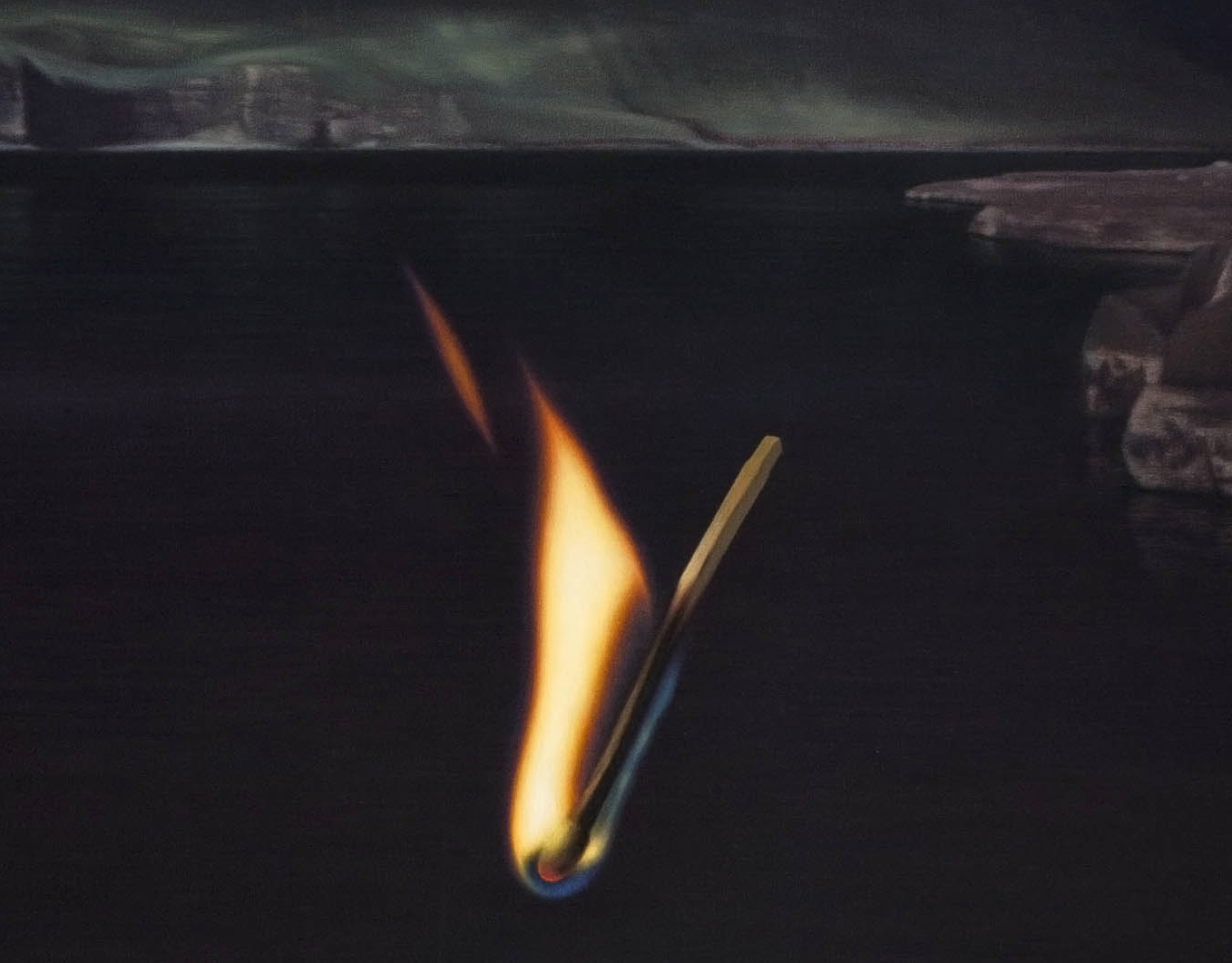

What Ben did was lock the keys in the running car, parked many miles down a dirt road pretty far from anywhere. No cell phones in 1991. I stared at the idling Preacher—every window closed, every door and the trunk with the tools locked, and I said the wrong thing: “What did you do that for?” I said this because I honestly thought Ben might have intended it as a conceptual art piece. After all, he’d once handed me a flaming sheet of paper in my parlor that read, “I rage.”

Ben kind of lost it as I examined the car. He yelled and cursed me. I ignored him; after all, the situation needed to be solved quickly. I realize now I could’ve placed something over the exhaust pipe to at least choke the engine and save fuel. As it turned out, it wasn’t that difficult to force down the power-window glass and snap up the lock, maybe 15 minutes.

That night under a modest moon, we lay in our separate hot-spring pools, steam rising as the air turned chill in a world so silent as to almost have a sound. There can be a true poetry to travel. For me it began as a longing and then an overwhelming desire from reading books by Stevenson about going to sea, or the treks of Basho through feudal Japan, or Guthrie and London riding freight trains, or Kerouac and Cassady driving automobiles across America.

Ben in the Preacher, the only known photo. Note the arrow I painted on the side the day Ben left for California never to return to Maine as a resident. [For many reasons this might be my favorite photograph of all time.]

We all know about the precariousness of expectations and how damaging they can be, but I must admit, I had believed that Ben and I would be joyously welcomed once we arrived in Seattle for the wedding. I had assured Ben of that. After all, these were my two best friends from high school, and during that era the three of us had been inseparable.

Admittedly, I had missed our senior year by quitting and taking to the road, but regardless . . . Murph and I had hitchhiked from the Midwest to Maine and back together at 16, not to mention our later southern run in the arrowed Nova, and Pete and I had hustled pool side by side for years, formed our views on honor and integrity mutually, and he had been the best man for my first marriage. In high school, Murph had emulated me to such an extent that many people had assumed we were identical twins or the same person.

Sure almost twenty years had passed, but weren’t these the bonds of a lifetime? Hadn’t I looked them up and visited during the early 80s to reconfirm our friendships? Hadn’t I given them both one of my early paintings? And now Peter was marrying Murph’s sister, and I had traveled across the country to witness the event.

But I’m getting ahead of myself in the road narrative. After Ben and I had left Los Angeles in the battered Preacher and eventually found our way to the abandoned hot spring river in an Oregon antelope reserve, that morning, we again headed north, paused in Bend where I found a string tie woven entirely from natural horsehair to wear with my cowboy hat, which I’d saved pristine in its box for the wedding.

As we crossed the wide Columbia River, I told Ben one of my favorite freight-riding stories from my cross-country run in 1980. About waiting all night beside the same ancient scarred icehouse where I had also waited six years earlier during my first run. I told him how I had ridden a flat car out of Pasco with a tiny Mexican tramp as a clear dawn opened around us. How we drank warm Rainer beer, and the vibration of the train created foam towers out of the bottle ends, the Union Pacific trains across the river looking like bright yellow lines in the warming sun. How we found a diner just opening alongside the tracks in Wishram, and I treated the tramp to a hot breakfast. In exchange he gave me a chart, which he insisted would allow vegetables to grow three times their normal size.

I thought of searching for the diner, but we needed to reach Seattle by late afternoon for the rehearsal dinner and festivities, and I was eager to see my old friends again. When we arrived in Seattle, I found a phone booth and called, finally getting Peter after trying twice.

“Bud, we made it! We’re here, in town. Can’t wait to see ya.”

But the conversation did not proceed as I expected. Basically, Peter mumbled uncertainly and then told me he would see us at the church at noon tomorrow. I was stunned. What had happened to the previous emphatic invitation? “And don’t be late,” he added. And don’t be late?

Ben and I found a budget motel room, and after much-needed showers, we sat outside on the hood of the Preacher, our backs against the windshield, and drank beer in the last sunlight. There wasn’t much else we could do.

At first I thought of just leaving, heading south and trying to outrun the depressing withdrawn tone of Peter’s voice. Then I changed my mind, remembering weddings could be confusing and complicated and our exclusion might simply be circumstances. The event was about the bride, not the groom’s friends. “Ben, we’ll put this behind us. We’ll go to the wedding tomorrow and be absolute gentlemen. Okay?”

In the morning, with dismay, I realized my entire forehead had broken out in a bizarre rash. If it was emotion or alien bacteria from the hot springs, I’ll never know, but at least I had my new hat for cover. At breakfast, Ben spilled maple syrup down his vintage yet new Beau Brummell tie that he was so proud of. But we maintained our poise.

Precisely on time at the church, we were almost the first ones there. We stood in the entrance room and waited. When I saw Murph come in, I beamed and walked over with my hand out. And he introduced himself to me. “Hi, how are you? I’m Murph, the brother of the bride. Are you a friend of Peter’s?”

When Peter arrived, he would barely speak to me and would not meet my eyes, but at least he recognized me. I’ll admit something right now: Murph’s sister, for whatever reason—I’ve never known since we had had such limited contact—had apparently never liked me, but after eighteen years I hardly expected that to remain an issue. But it was. When I asked for a photo with Peter—everyone in the wedding party posing for the hired photographer in front of the church—the moment was negated by her intrusion.

With the shock of her rudeness, I was beginning to falter. Learning that the actual ceremony was in 45 minutes, Ben and I dashed to a bar across the street and swamped a couple quick drafts. As we sat there, I didn’t know what to say, having told Ben so many stories about these two friendships—I had known both families so well, sharing much of their lives. To think how many meals they had eaten from my mother’s kitchen, or I theirs. “Darn,” said Ben. “Wow.”

We made it through the ceremony and then Preachered to the reception where I dropped off my wedding-commemorating artwork, which I had carried 4,000 miles as a gift for the bride and groom. At least Peter’s mother and sister along with Murph’s wife were delighted to see me, although when I was asked to remove the hat, I declined—vanity taking precedence over agreeability. That one concession aside, Ben and I maintained our gentlemanly behavior for nearly a couple hours, then we bolted.

This photo shows Murph, Peter, and myself at the reception (the one stolen moment while the bride was otherwise occupied). Makes me wonder if anyone ever knows the true story behind a photograph.

As a footnote, Peter called me ten years after the wedding and tried to apologize. Problem was he kept bursting into tears. The marriage had turned out to be beyond impossible, and the divorce custody fight had lasted eight years, destroying Peter financially, careerwise, and even dumping him in jail more than once. I still haven’t seen either Peter or Murph in person again.

Leaving the reception, Ben and I landed at the Redhook Ale Brewery, where, I’m embarrassed to say, we both overdrank. On exit, it was the one time during the trip that I took the wheel, the old car solace somehow, getting us out of Seattle. As the evening sun slanted through the Preacher, Ben began to pound the dash with his first. He hit it hard enough and often enough that the vinyl cracked and foam padding began to crumble out. “Ah, Greener, ah, man, damn it, damn it,” he said over and over, the tears now on his cheeks, my face a mask.

The next morning, we decided we needed at the least to wash our faces in the Pacific. My hangover was akin to a furry crocodile, my mood worse. We found a beach on the map, but once there, the ocean was cacophonic with jet skiis. For the first time in my life, I craved a rocket launcher. The repression of the day before was surfacing, and Ben, during our recent memory-refresher phone call, insists he had to restrain me from attacking what I considered overly rude people. He also said I never showed any negative emotion during the time of the wedding. This I was surprised to hear considering I remembered being a washing machine on agitate cycle.

We followed the coast south. We stopped for a hunk of Skagit salmon, which was rather tough and overly salty yet helped physically. But the Sequoia forest was heavenly in its majesty and its drizzling quiet. Driving through an ancient Redwood is something you never forget. And then we crossed the inimitable Golden Gate Bridge and my last true road trip had ended.

One of the basics of writing good fiction is balancing the torturing of the reader with the payoff of a reward. Writers attempt to form compelling characters and then allow circumstance almost to destroy them. This hooks us into the novel because we want to know if they will survive their desires, risks, and enemies. After a certain amount of torture—this can’t go on for too long or the reader gets annoyed—the writer relents and grants the character some wonderful fortune. Dickens was the master of this give and take, up and down.

Life is not fiction. And in reality, three or four people can collide cruelly through no fault of any of them. This is fate and can lead to tragedy. Many times, clear communication can avoid these problems, but on occasion even that is impossible. We all want different things and solve issues in a variety of ways, and, of course, no one can know the future on which to base his or her actions.

Road trips are many times poetic simply because of what we bring to them. If Ben and I have a Kerouacian-style dream, then we will be pleased with that kind of trip. If European five-star hotels are the vision, then the time travelling between and staying at them will be just as appealing.

A forum friend, Sarge, wrote: “Poetry needs a dream.”

I think he hit an often-overlooked bull’s-eye with that phrase. The quality and poetry of a road trip is up to the travelers to create by what they focus upon and how they judge what happens and what’s around them, even if it’s wrenching a water pump in 100-degree heat. The morning after the wedding, I found everything unbearable, but that was the issue of my mindset, and by afternoon my world expanded again. Road trips are blessed by constant change and thus contrast, which might be one reason they leave vivid memories.

In life, as it is on the road, we need to find what fits us, and then it’s our willingness to give our hearts to that thing that matters—the rest is far less significant. At least that’s my conclusion.

That ‘prize photo of the Preacher’ is OK, however that is NOT an “Oldsmobile Delta 88 Royale Holiday Coupe”. I owned one, and any gearhead would know that the picture is of a 4 door sedan. Way to embellish the story!

The car in the photo is a 1976 Oldsmobile Delta 88 Royale 4dr hardtop. I’m pictured in it.

In the 30 years I have known the author, he has owned, driven and maintained multiple pre-1966 Chevy Impalas, a Porsche 911, Ducati and BMW performance bikes and vintage Velocete. Still, I doubt he would describe himself as a gearhead.

To say Eric misstated the 1976 Delta 88 Royale options as an intentional “embellishment” to the story is obtuse. Perhaps you don’t read much?