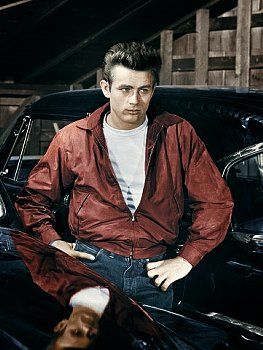

Here I am in 1981 a few months before my meeting with Gregory Gillespie. The painting on the easel Marquee was one of the three I brought to show him. Note my innocence! Both Polaroid portraits by Michael Cerulli Billingsley.

Terry watched her, how she acted in public, and it bothered him; she was always looking around to see if there were admirers. This made their relationship feel even more foundationless, although she insisted that wasn’t true. “You is crazee,” Giselle would say, tossing her signature locks. He supposed their bond was primarily sexual—they were in their early twenties after all—but her hunger for admiration and male interest seemed disquietingly insatiable.

He’d married her to keep her in the country—they met in Paris—and he was continually suspicious that American citizenship had been her goal all along. That rainy night when he’d been fortunate enough to sneak her across the Canadian border into Vermont, he’d seen her sheer stubbornness for the first time, she demanding they return to the customs depot so she could have her visa stamped.

“But you’re already in the country,” he said. “You’re in! Giselle, it’s fantastic. It’s amazing they never asked you a direct question. You don’t need anything.”

“Non. I must ave eet.” Her English wasn’t so great, which is why he’d begged her not to say anything at customs. She’d merely simpered at the man with her huge eyes and pouty lips.

When they had finally turned around—Terry by then worn out from attempting to convince her—the border guards had spent over three hours dismantling the 356 Porsche. They had even unbolted the steering-box cover plate, from what could only have been malice, a response to being deceived. Luckily they had only removed the seats and not cut through the thick leather. This mistake had begun a series of three-month visas that required renewal and eventually expired altogether. But he believed he loved her and wanted her to stay with him. His loyalty was absolute, more from his own nature—as he would eventually find out—than because she deserved it.

They lived in near poverty in a cheap duplex next to a river in a northern Vermont town. The apartment was continually drafty and damp, the stonewall that held back the rushing water mere yards from the exterior of the structure. In the winter or during heavy rain, the flat roof leaked, streams sometimes running down the ugly paneling. The bitter elderly landlady was no help. “The roof never leaked before you moved in,” she said in dismissal.

Giselle blamed her lack of English when it came to finding work, so their income was his problem. Terry’s dream since he was thirteen had been to be an artist, but he labored painting houses and driving one week a month to Montreal to assemble pulp testers eleven hours a day for a tiny company above a poisonously odoriferous drycleaner. Between the two jobs he worked relentlessly on his art and attempted to keep his wife happy. There was no house painting in the winter, so during those months, besides the time in Canada, he painted up to fourteen hours a day, his brush water freezing overnight, his hands so cold he had to wear gloves on occasion, the kitchen the only room with a decent heater. One year he finished eleven paintings and destroyed ten. He had a clear vision but couldn’t quite seem to find it.

As a teenager, he had been successful selling paintings of conventional realistic landscapes and interiors, buying his vintage Porsche from the money he’d earned, yet he wanted something more. He was influenced by Japanese thought and haiku, hoping to create paintings that were as much about the moment of seeing as about technique. He utilized carefully constructed compositions and flat planes of clear color, and after a few years, believed he was succeeding. He sold the Porsche and bought a vintage Volvo wagon so that he could paint larger pictures.

During these years, Giselle took long walks by herself. She disappeared for hours on end, sometimes returning after midnight, never willing to explain where she had been. “It is nothing, Terry. I am needing this time alone.” He was especially in agony while in Canada, sleeping on a cot in an unheated enclosed porch of a family friend, wondering what she might be doing. He suffered but was too busy to become depressed. Then, on occasion, she began to bring strange men or couples home to the apartment. One of the single men saw some of his paintings and was stunned. “Do you have any idea what you’ve accomplished?” he said.

Soon P. D. Reno planned a trip to New York City for the two of them, Giselle’s flirtations being outweighed by the power of engaging artwork. Reno insisted Terry bring an original painting along with professional slides featuring his new work, and they eventually ended up in the office of Ralph F. Colin, who, besides being one of the most prominent lawyers in the city, had also founded the Art Dealers Association of America. His collection of Matisse, Soutine and Vuillard was barely contained by a massive coffee-table art book. Of course Terry knew none of this that morning. After a half hour of intense questions, Kolan said he wanted some time alone with the painting and the slides while Reno’s father, a lawyer in the same firm, took them out for a lunch.

Terry had never been to a private club before. After the embarrassment of being tented in another man’s forgotten jacket and snared in a gaudy tie, he was, simply put, overwhelmed. People ate lunch like this? Huge sloped beds of hammered ice cupped every kind of seafood he had ever imagined—cracked lobster, three kinds of crab, dozens of foreign bivalves lay in a matching variety of luminous shells. Steaming roasts were carved by samurai knives balleted by swarthy men in impeccable white uniforms, but the shock came when Terry returned after excusing himself mid-meal—his plate and the half-dozen confusing utensils were not only new, but his food had been artistically rearranged. It was an alien world, and Terry promised himself never to be so unprepared and unknowledgeable again.

It was a blindingly nervous moment reentering Colin’s office. His painting had been hung precisely on a prominent wall, Kolan greeting him with a smile of approval. Terry sensed he had crossed some kind of magical line, and forced himself quiet and calm.

“With your permission, Mr. Stafford, allow me to see what I can do on your behalf. Is that agreeable to you?”

Agreeable? Terry could only nod at the bizarreness of a dream coming true. And wouldn’t Giselle have to rethink everything now?

Colin was obviously a very sought-after and busy man, but within six months he had introduced Terry to two major New York galleries after almost enticing Andre Emmerich to represent him. It was unthinkable yet true. He met with both dealers and chose the Borum Gallery over Midtown Gallery because the rooms at Borum where far less cramped and Bella Carpko seemed more energetic and excited by his work. As it turned out, Midtown Gallery would close its doors before the decade ended.

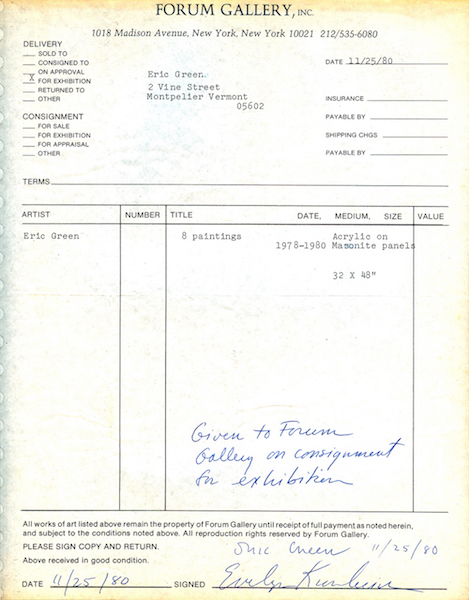

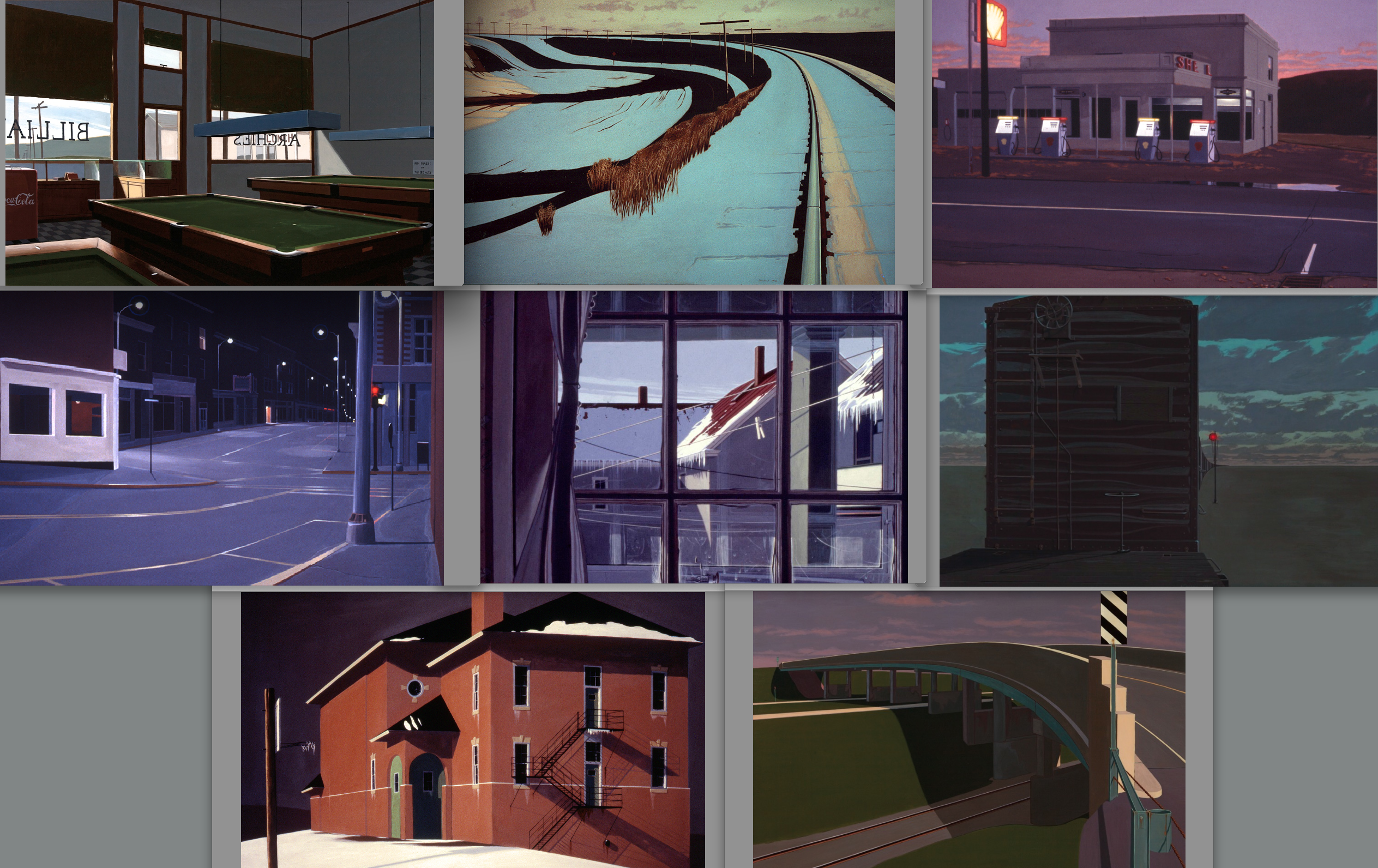

The Forum 8: Poolroom, 1977; Passage I, 1978; Shell, 1978; Onyx, 1979; Glance, 1979; Passage III, 1980, Annex, 1980; Passage IV, 1980

[These paintings never saw a public wall until last summer when Jake Dowling from Dowling Walsh Gallery was willing to show them. That was a long wait, eh? Thank you Jake and Mary Dowling! You two are the best. Your support and belief has meant the world to me. As an aside, Jake Dowling has sold, over last couple years, all but one painting in the 30k price range.]

One cold November morning, Terry carefully stacked his eight paintings into the back of his Volvo and drove from Vermont to Manhattan unloading the work on Madison Avenue. Bella could not have been nicer or more complimentary about the originals, and he was offered a show for the coming spring—this was unusual, but the newly opened timeslot due to a cancellation seemed provident. Other patrons in the gallery were also excited by Terry’s work, and he even received a dinner invitation, which he declined, feeling more stunned by all the attention than anything else. He realized that all his years on the road—hitchhiking and riding freights across the country many times—hadn’t prepared him for anything like this.

After looking at the paintings, Bella began talking to him about Gary Hellespie who had just had a retrospective at The Hirschhorn Museum, reviewed by John Canaday and titled Why the Whitney Should be Kicking Itself. She was shocked Terry didn’t know of him, so she gave him two softcover books of his paintings. “You must study Gary! You must meet him!” she said. “He’s a genius. He was just twenty-six when I discovered him, and to think you’re only twenty-three. Maybe you’ll be my next Gary? What do you think of that, Mr. Stafford?”

Terry went to a bar. He felt at home in the old place, which had remained unchanged since the 1930s when it had been called The Gaiety. The colorful vintage neon over the angled street-corner door had appealed to him. He sat drinking drafts at the long wooden bar top, attempting to understand what had just happened. He took out the paper the gallery secretary had given him and read it again: “8 paintings given to the Borum Gallery on consignment for exhibition.” He wanted to shout but ordered a turkey sandwich instead. Then he called Vermont from the payphone near the door and told Giselle. For once she seemed truly pleased.

It snowed lightly as he drove north up the Taconic Parkway toward the dawn. He still felt unreal more than elated. Was this how it was when dreams were realized? At least he knew the work was solid; he had put everything he had into those eight paintings. He’d need to borrow money to buy a suit and some shoes. He’d always craved fancy shoes, and with painting sales imminent, he would finally have some real money after so much skimping. Would Giselle start spending it? She seemed always to be wearing something new, claiming she’d found it at Goodwill for pennies. Once his mother had pulled him aside and said, “You realize that’s about a four-hundred-dollar sweater, don’t you?” He hadn’t known how to answer, wondering how his mother would know. Would Giselle lie?

And then during the weary and nervous month of February, Terry telephoned Gary Hellespie. The older man was rather formal, almost unfriendly, decidedly arrogant on the phone, but Terry asked if he could come visit and show him his latest work, which Terry was tremendously excited about and felt was a leap forward from the ones at Borum.

“I’ll need to see slides first,” said Hellespie.

Terry was a bit taken aback—weren’t they in the same gallery? Didn’t that mean anything? Hadn’t Della Carpko told him to contact Hellespie, almost requesting it? Again, it was a world Terry knew nothing about. But he promptly mailed the images that had gained the admiration from Colin and Carpko. After waiting impatiently over three weeks for a response, Terry telephoned Hellespie again.

“Yeah, I got them.”— “I suppose they looked okay. It’s never easy to access much from slides.”—“Yeah, I suppose you can come down, although I’m quite busy right now.”

Regardless, they set a time and date.

Do we sense the major mistakes in our lives before they happen? Are there warning voices? Some kind of vague sign that the road around the corner ends in a sudden severe drop?

It was the end of March when Terry loaded his three new pieces and Volvoed to Hellespie’s studio in Massachusetts. He was wearing his new shoes for the first time, figuring he’d break them in so they wouldn’t be too uncomfortable for the opening in New York, which was now under six weeks away. His show had been named Terry Stafford: New Talent. He was very proud of the shoes, if rather embarrassed he’d spent over a $100 for them, which was close to a month’s rent. “Irresistible” was how he rationalized the cost. They were Italian bone-colored wingtips with an almost skin-like greenish cast, a tall stacked leather heal, and a perforated stylized PC for Pierre Cardin, looking more like a mushroom than initials.

The shoes in 2017. I still wear them to each of my art openings.

Slightly early, he ended up waiting nearly two hours in the cold March wind for Gary Hellespie. He thought of telephoning, but that required finding a payphone, and he didn’t want to miss the man, expecting him every moment. When he finally showed, he immediately commented on the shoes.

“You don’t like them?” said Terry.

“I suppose they would be appropriate for a gigolo or a pimp.” And after a few moments, “I talked to Bella about you . . .”

“Really? What did she say?”

“She seems quite taken with you.”

Inside, Hellespie showed him what he’d been working on. The painting was huge by Terry’s standards, probably seven-feet square, depicting a series of over-sized levitating eggplants, carrots, turnips, tomatoes and a squash on a common dark background. The vegetables were miraculously rendered down to every blemish and each bead of moisture, all in oil paint. Terry stared for a long moment, uncertain what to say. He was still a bit miffed about the denigration of his shoes. The comment seemed uncalled for.

“That looks like a lot of work,” said Terry.

“Eight months.”

He was silent, trying desperately to think of something appropriate to say. He always had trouble lying. Even as a kid he couldn’t seem to lie. He simply went mum. “They really really look like vegetables,” he managed. “Amazing how much.”

“You don’t like it?”

Could the man read his mind? “It’s different than your other work I saw in the booklets, so it’s taking me a moment to adjust.”

“Different?”

Some of Hellespie’s early paintings during his twenties had been interesting, perverse, sexual, referential in terms of art history, maybe a bit grotesque, but clearly creative. Terry had genuinely admired some of the street scenes done in Italy. This painting seemed like an exercise in futility. Why render a bunch of floating vegetables? Wasn’t the point of art to be more than the sum of its parts? Shouldn’t the work touch the viewer, have some meaning or emotion besides what it so blatantly reproduced? This could be merely a montage of cutout photographs.

“Maybe some of your earlier paintings might have been a bit more challenging.” Terry knew instantly he’d said the wrong thing, but had no idea why. Would Hellespie care what Terry thought of his painting? It seemed improbable. Hellespie was famous, successful, why would he give a second of emotion to Terry’s opinion? Hellespie shot off into a backroom and returned with a relatively small painting of a naked baby on immaculately rendered stone and tile steps onto which blobs of oil paint, as if the actual palette had been smeared into it, were stuck onto the surface of the panel.

“Like this? Is this more challenging?”

To Terry’s horror he didn’t like this one any better than the vegetable medley. Hellespie had remained reasonably polite, but Terry could tell he was annoyed, which was confounding. He was shocked the meeting was going so poorly and didn’t understand why. Then Hellespie suddenly insisted on seeing his paintings, so he returned to the Volvo and brought them inside, telling himself to try to improve things, although he had no idea how. He sensed he could come across as arrogant when it was really just a lack of social skills. You didn’t learn those in poolrooms and hanging out with hobos.

But Hellespie adamantly disliked Terry’s three recent paintings. “Della said you’re self-taught and it shows. You desperately need dialogue with other artists. My advice to you would be to enroll in a good school and learn the basics, meet other artists your own age, receive their critiques along with the guidance of a competent professor.” This sounded so condescending that Terry felt himself getting defensive. He didn’t tell him he’d attended RISD for one week at sixteen and turned down the proffered full scholarship. Hellespie’s remarks stung deeply, but he tried not to show it. Couldn’t Hellespie see what he’d accomplished? Maybe these new paintings weren’t so solid after all? “Can you tell me specifically what you don’t like?”

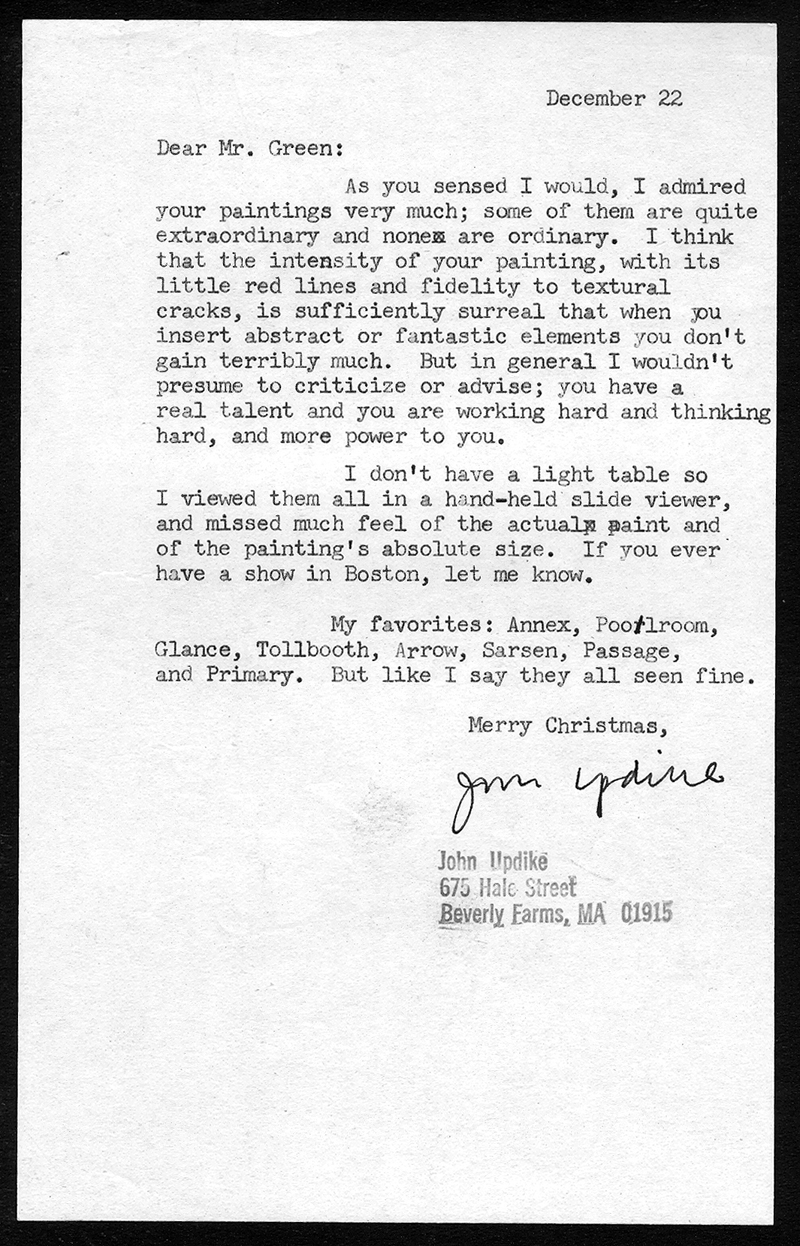

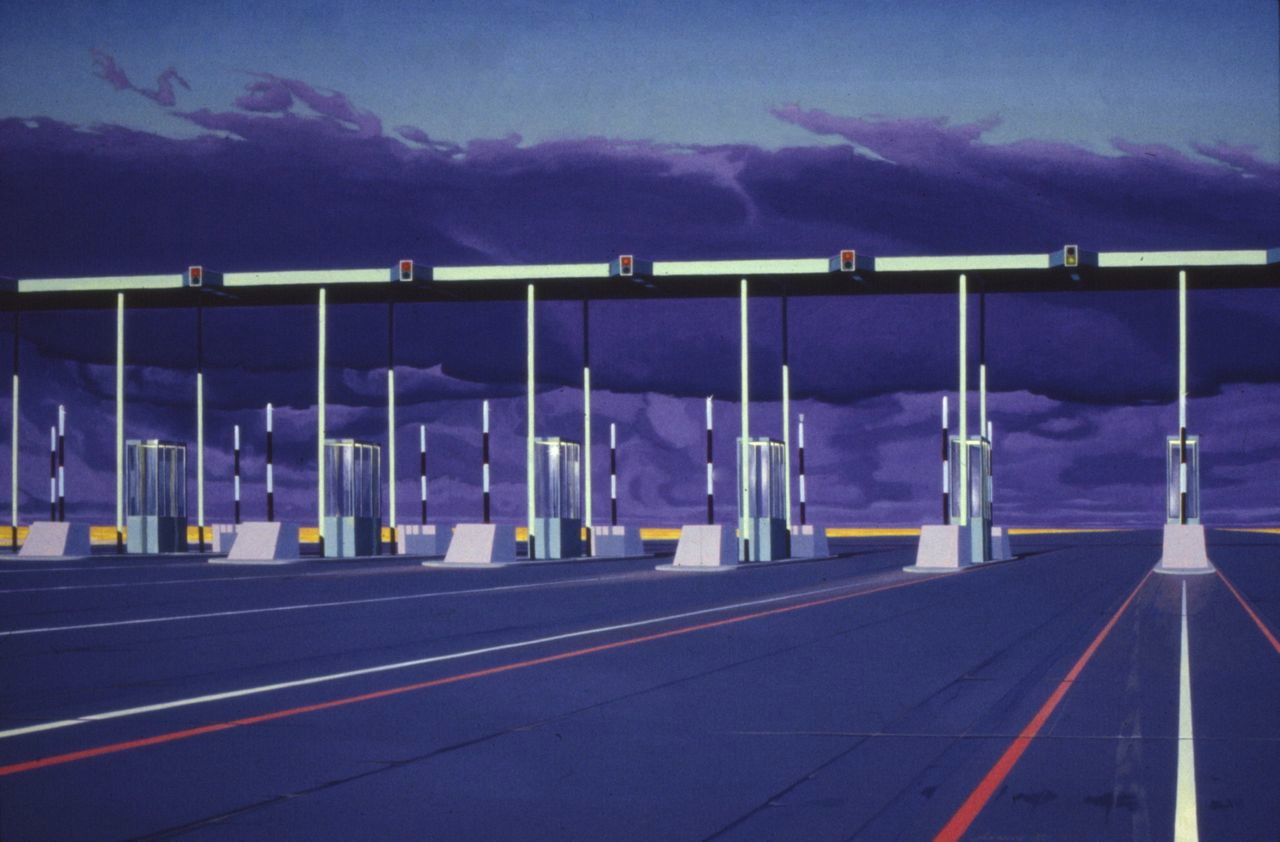

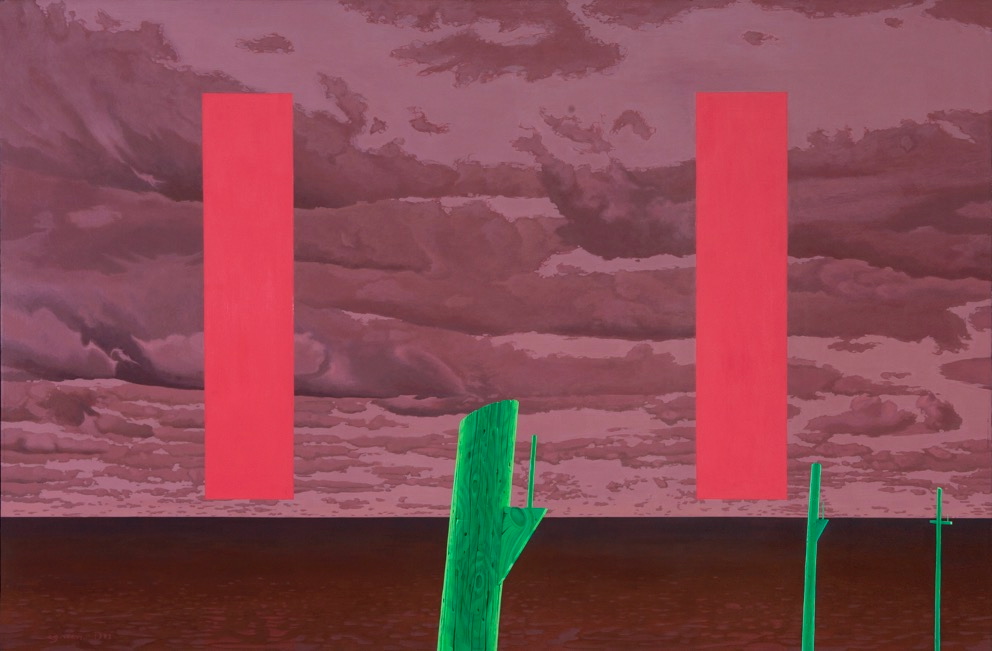

One of the paintings was of a tollbooth in brilliant sunlight, the booth vibrant lime against a huge rising storm cloud of dark purple, the image invented, the booth his own design, based on a moment Terry had experienced hitchhiking. Terry had wanted to prove that the ugliest colors could be made beautiful in the right contrast. The painting would much later be noted by John Updike as one of his favorites in a letter to Terry. Hellespie now pointed at it:

“Like this thing! Everyone in New York is doing this. What’s the point?”

Terry attempted to explain, how three identical trapezoids formed the composition, how the tollbooth poles moved in a sequence toward each other in the perspective like two lovers coming together, how the one half of the rising cloud was the other half moments later, attempting to express time passing. In the next forty years Terry would never see another painting of a tollbooth remotely like his.

Terry went to a bar. He knew the area from having lived in the Wendell woods when he was seventeen and eighteen, a time before he had found a cheap flight to Europe and met Giselle. Brokenhearted after his meeting with Hellespie, he began to drink drafts and hustle pool. He couldn’t be beaten. The bets increased. All the guys shooting pool were black. When a new guy walked into the bar, one of the players would call out. “Gerome, man, git your ass over here and take this honky mothafucka. He holdin’ all our bread.” Terry left with well over seventy-five dollars, pretending he was going to the bathroom, running after he exited, just in case—this was a world he understood. He backtracked carefully for his Volvo and headed home.

About a month before his show was to open, their one phone, a red wall phone in the kitchen, rang. Terry stared out at the last remnants of early April snow as he answered. It was Bella Carpko:

“Mr. Stafford? I’m sorry, but your show has been cancelled. Please come and collect your work as soon as you can.”

Then the line went dead.

Terry called the Borum Gallery back immediately, but they were sorry, Della had already left for the day. Of course, they would give her his message. He called twice a day for a week, but she never seemed to be available to take his call. After two weeks, his despair was overwhelming. Finally, reluctantly, he telephoned Gary Hellespie.

“That’s too bad. Sorry to hear that.”—“Do I know why?”—“I suppose I might have mentioned something to Della. I might have told her I didn’t think you were a good fit for the gallery.” Terry could hear the man’s smirk over the wire—a garrote—as he hung up.

Within weeks, Terry began his bouts with bleeding ulcers.

Terry thought of sending Hellespie a hyper-realistic painting of a bitten off carrot, but in the end, he never mustered the energy.

Even when Terry collected his work at Borum, he never saw Bella Carpko again.

Within the year, his father died suddenly of a heart attack in the one place on earth he hated the most, JFK Airport, and after claiming the body in New York, Terry began to take care of his mother, a task that would last for almost thirty years.

His marriage with Giselle ended after she confessed to all the other men she had been having sex with during their relationship. She said the impulse behind her confession was to come clean, find honesty between them, because she truly and finally loved only him now. She claimed sleeping with others was the only way she could know for sure that he was the one. She was fiercely angry when he declined her offer of eternal love. After their divorce and settlement, in which Giselle would take everything Terry owned including five paintings (one from the group of eight that never made the wall at Borum) and Terry’s dead father’s car, which she promptly rolled into a ditch and abandoned, he would find out that Giselle had been fabulously wealthy all along, her family owning many six-story Art Nouveau buildings in Paris as well as over 40,000 acres of land in outlying hamlets south of the city.

Terry refused to show his artwork for almost ten years, and his trust in people never returned.

Twenty years after their meeting, Gary Hellespie hung himself in his studio in Massachusetts. He died owing the Borum Gallery over half a million dollars. Out of love or loyalty, Della Carpko had continued his yearly stipend long after his work had stopped selling.

No matter how Terry has searched online, he hasn’t been able to find the Hellespie painting of the floating vegetables, although it might well have been a precursor for much of the popular hyperrealist painting of late. Terry, for what it’s worth, finds that he isn’t any more moved by the new flotilla of well-executed hot house wonders and sweet desserts than he was back in 1981.

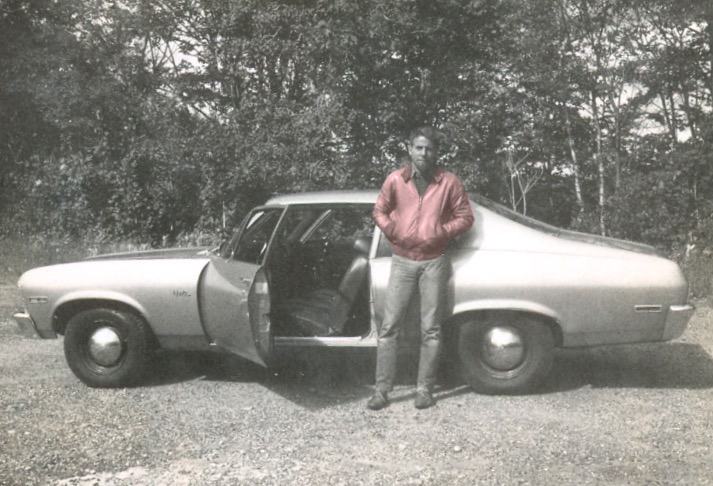

Here I am a couple years after my meeting with Gregory Gillespie. Note the shoes, which were brand-new in the first photo. I’ve begun to lift weights and I’m learning to box. The painting on the easel is called Departure and was [is] about the death of my father. The gloves on the window sill are handball gloves. The red leather jacket was custom-made in honor of the windbreaker James Dean wore in Rebel Without a Cause. Montpelier, Vermont, 1983.

A B&W postcard I hand-painted-colored in 1983.

Me on my BMW R90S about the same year.

Departure, acrylic on panel, 29 by 44 inches.

Two letters that substantiate my story: