Photo was taken in the farm fields of Wisconsin, January, 1975. The temperature? Only a tad under 5, but I thought my polyester pearl-snap suit had quite the look. I only look cold because of the wind (always raging across those flats) and the fact that the 356 had no functioning heat at this time. Soon enough I closed some of the large holes in the heat exchangers with tin and duct tape. Better? Only very slightly, but it felt glorious, even if it was the kind of heat your favorite pet blows against your chest on a cold afternoon in bed.

Photo was taken in the farm fields of Wisconsin, January, 1975. The temperature? Only a tad under 5, but I thought my polyester pearl-snap suit had quite the look. I only look cold because of the wind (always raging across those flats) and the fact that the 356 had no functioning heat at this time. Soon enough I closed some of the large holes in the heat exchangers with tin and duct tape. Better? Only very slightly, but it felt glorious, even if it was the kind of heat your favorite pet blows against your chest on a cold afternoon in bed.

Winter 1975 In Neenah, Wisconsin, I take my “new” 1956 356A 1600S Porsche to an English mechanic recommended by my father. Not only does he damage the car by pushing it out of a snow bank with his plow, but he also steals many Porsche parts and replaces them with cheap VW ones (the horn suddenly made the distracted bleat of a sick sheep). He also pinches a brake line while jacking the car, which would lead to a brake failure at 80 mph when headed into the Rocky Mountains. At this point I still trust people, so have no idea how poorly I’ve been treated. I pay his ridiculous bill. Remember, I am still just 18 years old.

I drive to Ocean Shores, Washington to visit my father who has taken a job in Aberdeen and bought a house, building an enormous garage for his 911 Targa. My mother is stuck in Wisconsin trying to sell that house.

My father stupidly bought a house on Ocean Shores, and I went to visit him. My high school buddy Eric Murphy (I drove to see him in Portland, Oregon) blew up my Porsche engine within one minute of driving the car for the first time. He immediately accelerated flat out to over a 100 mph and then shifted back into third. I simply could not believe he could be such an asshole. I asked him what the hell he thought he was doing? “Well . . . you were driving it that way.” Even though we were only 18 years old, I will never forgive him. But it stranded me, and it took months to find a new engine, and after two tries I was finally running again with a much slower motor than before.

Then the man who had hired my father committed suicide, so my dad was fired. Then the entire chimney blew off the side of the house he’d bought. He ended up returning to Vermont in financial ruin, and I drove one of his cars back across the country for him although he had refused to help me repair my 356. I begged him! All he had to do was tell me what to do—he was a master mechanic and had just build himself a huge garage. Instead, he once again cheated me by talking me into selling my broken Super 75hp engine to a “friend” of his. He did the same thing with the amazing Marklin train set my grandfather had bought for me when I was around 12 or 13. It wouldn’t work because it ran on 220 volts, but he could’ve easily bought a converter. But then he had never wanted me. My mother actually told me that at 13 years old to try and further set us apart. It worked for a while.

But the trip across the country—my first big run in the Porsche—was a classic. Initially, I visited Ripon College, met Rich Bruce and saw Kathy Carlsberg, who I had had a huge crush on in high school. She had always kept me at arm’s length because I’m sure she saw me as too puny and unattractive. But even with her amazing Greta Garbo looks and perfect breasts, she chose misbalanced dominoes of abusive men until the age of forty when she finally found the right guy, at least as portrayed in her Christmas letters.

There was a moment on that trip West that no one will believe, but it’s true. As I mentioned, I lost the brakes at 80 miles per hour coming off an Interstate exit towards a stop sign. When I pulled the emergency brake, the rusted cable snapped and I was left holding the T-shaped chrome handle. I downshifted as the revs would permit, slid through the dead-end corner in a four-wheel drift, and basically enjoyed the entire moment as pretty exciting, but later in the day, toward dusk, I would finally become truly scared.

In the Rockies, on Interstate 90, I was met by a massive mountain blizzard. It became apparent the Interstate was becoming impassible so I took the first exit and began searching for any form of human habitation. Cold? Very. Remember the Porsche didn’t have heat. Also no brakes. Then the Wipers stopped working. To see—I couldn’t pull over or stop or I’d be stuck and stranded and freeze to death—I attempted to roll down the window, but the mechanism jammed, so I had to open the door, hold it from flying completely open, peer through the crack into blinding flakes, steer and downshift for brakes with my other hand while maintaining the momentum of around 50 mph. Just as the pan of the car began to lift in the mass of snow drifts, and darkness had all but made visibility impossible, did I spot a motel neon. Imagine that sight! God does exist!

The next morning it was 20 below zero and no one’s car would start except my 356. How? A chicken baster—I extracted gas from the tank under the bonnet, injected the fuel into the four carburetor venturis, and off I went. That morning I also called my father, and I drove to the one official Porsche dealer in that part of the world during 1975. They fixed the severed brake line as well as the leaking gas filter, which had dripped constantly on my right shoe. Life was good!

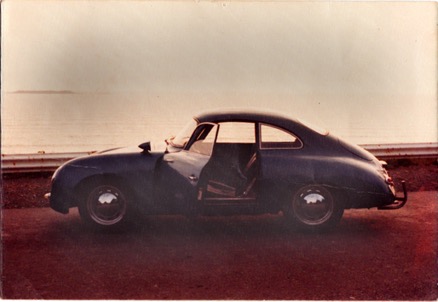

My 356 on the West Coast. My father convinced me to detach the front bumper—weight reduction. He then left it behind in Wisconsin, refusing to move it. Funny what that bumper is worth today. Or maybe not so funny.

Slower Porsche engine (1500, 55hp) fitted, I drove back across the country on Route 12, missing the racing Bursch Extractor and the extra horsepower. I think I’m the only person who has driven across the country on almost every non-Interstate highway that bisects the West. For instance: Route 2, Route 12, Route 14, Route 20, and Route 36, just to name a few. At times because of construction, the road would jag north for 40 miles, head east 5, and then return 40 miles. This becomes mentally exhausting after a time, even knowing that the point of being there is the road travel not the achievement of distance.

On a long driving trip, it’s not easy to turn around and backtrack. Maybe during the afternoon you suddenly remember that you left your dead father’s sunglasses in the diner where you ate lunch, or you realize that you took the wrong exit an hour ago—the sun is behind you when it should be slanting through the windshield.

It can be discouraging when you discover the mistake. Sometimes you might even stubbornly keep driving before accepting that there is nothing to do but U-turn, compounding frustration. You might pull over and glare at a map, hoping there’s some other choice, a shorter way, anything but the next hours of correcting a carelessness that will achieve so little.

One night after an endless day behind the wheel, I noticed the winking lights of the Starlight outdoor movie theatre fly by for a second time. “That’s odd,” I thought, “how can there be two Starlight theatres within hours of each other? And on opposite sides of the road?” Then I felt like crying.

Life can be like this. No one wants things to get worse or head backwards, but they do. People invest their futures with Madoffs, they crash cars, they’re diagnosed with cancer, houses burn to the ground. We want to say, “No! Please! Reverse this last bit of film; this can’t be happening.” We are captive within not only our own natures but human nature in general. The realization of improvement gives us joy; deprivation and loss generates misery. Doesn’t matter where the mean water level is, or how high the rise or deep the drop.

One morning in the fall of 1974 I stood on a boxcar floor stranded in a freight train a few miles from the Canadian border in Montana. It was so cold that I was forced to jump up and down, my wool blanket wrapped around me like a poncho. I hadn’t eaten for almost a day, and I could see the fluorescent welcome of a diner in the predawn darkness. Chilled, hungry, despairing, I had all but decided to abandon my westward pilgrimage when the freight lurched and began to roll again. 20 minutes later the sky flamed into the most overwhelming sunrise I’ve ever seen. I was inexplicably happy. The day turned into a miracle of experiences that I still cherish.

Is the point of life to remain safe and live as long as possible? To gratify and enjoy oneself? To try to help others? To raise a family and protect them? To become rich and powerful regardless of the cost? To make spiritual gains? To learn about and understand what’s around us?

I haven’t a clue what’s right for others. I only know that if I’m forced to U-turn and backtrack, it serves nothing to become frustrated or bitter though that’s not always possible to manage. But I know that eventually I’ll have to accept what has happened—drive back those many hours to retrieve my father’s sunglasses, deal with the fact that I’ve lost a lot of money, that my ceilings and belongings are ruined, or that someone I love is going to die. And who knows, though I certainly can’t see it at the moment, I might actually be headed in an ideal direction, the day in front of me about to open into a long-awaited miracle.

I visited Kris in Watertown once again. He, however, got mad at me and kicked me out of his room and his side of his parent’s house because I did not agree that the most brilliant statement about art was this: “Art is!” My feeling was that a modifier would make the sentence more meaningful. I also was asked by his father, who owned an AMC dealership, to park my foreign junk a block away so no one could see such trash in his driveway. The 356 was so disliked at that time that I was refused gas in certain stations and was once told to, “Get that Nazi shit off my property before I blow a hole in it!”

Only his mother, Edie, who sat long hours with me at their basement bar area, drinking beer and talking about life, and his brother Greg, seemed to appreciate my presence and company. Greg was even always willing to give my old crate push-starts since the starter motor had long failed. Parking on a hill wasn’t continually possible. When Greg died, I wrote this to be read at his funeral:

“I first met Greg when I was around seven or eight years old. My parents had hired him as my babysitter because our families had been neighbors on West Broadway Avenue. Even at that age I immediately liked Greg. That was one of his gifts, everyone seemed to like him, but as a babysitter I’m not sure my parents approved.

What we ended up doing during the four or five hours my parents were gone, was burn all my carefully assembled plastic model cars. This was one of my first experiences with paradox. On the one hand, I was very proud of my cars, but on the other hand I was apparently also a bit of a pyromaniac, something Greg and I obviously shared. But I still clearly remember the evening in the backyard, Greg and I staring into those smoky flames, the plastic, aided by extra glue, burning feverishly. And Greg must have marvelled at it as well since he consistently reminded me of the moment over the years, laughing in that delightfully self-effacing way he had. “Maybe I wasn’t that great a babysitter, making you burn all your models,” he’d say to me thoughtfully, almost apologetically.

During my teenage years, I played a lot of pool, and Greg was always up for a session. Whenever I hitchhiked or later on drove into Watertown, we met at one of the downtown poolrooms or at the basement pool table in the Broadway house. You learn a great deal about a person’s character while playing pool with him, and Greg was my favorite competitor. Relaxed and calm, Greg played with a sweetness and sense of honor that affected my behavior towards the game. Greg always tried his best, and we were very evenly matched, but he had a graciousness about him, and he always wanted me to play well, and was pleased if I made a particularly difficult shot. This is unusual in good pool players. But Greg was unusual. He had a fragility, a delicateness, his handsome finely boned face so open, as if the world with all its aggressive endless desire and greed might have been a bit overwhelming for him. Greg consistently exhibited true kindness and generosity in our experiences together. Two attributes that I hugely respect and admire.

When I was in California in 1983, I visited Greg. He was amazed that I found him, that I cared enough about him to put in the effort. He seemed unduly pleased, and again, we had a wonderful time. I can’t remember not having a wonderful time with Greg over our forty-five years of intermittent encounters. Whenever we met, we immediately began talking comfortably and laughing together. Something simply clicked, which I know was more due to Greg than myself, since I’m not always easy socially.

One of my novels has finally been published this year. And Greg is in one of the characters. As a matter of fact, it was our meeting in California in 1983 that might have started my trying to write a novel twenty years ago. That one wasn’t much of a novel—pretty awful actually—but the Greg character who I named Kelly Harris is in two of my books. Of course Greg and I won’t play pool again, and I doubt we’d want to burn model cars, but for me and my readers, Greg will quietly live on in that lovely modest way of his. He had a wonderful influence on my life and my work, and I will miss him dearly. Good-bye, my friend.”

Kris was taking a pottery class in Clayton near Thousand Islands. We drove back and forth in his Rambler, smoking pot, and he introduced me to Led Zeppelin as well since I’d never heard them before, being a blues or avant-garde jazz or Jimi Marshall Hendrix listener only. Even at 14 I did a watercolor of Jimi that the school purchased. It was later thrown away when a student broke the glass of the frame. How I would love to see that again. I like Zeppelin okay, better than pot, which just made me feel stupid, which I found tremendously boring.

Then Kris and I set out on our classic road trip through New England. This will be featured in another posting; I leave you with this poem about our trip until then. The first few lines was an attempt to replicate a very famous Chinese poem—the feeling and sound hopefully transitioning from very light to fully weighted.

ATLANTIC

On light wings we came

Following pretty girls in old cars,

Salt brine reaching our nostrils

Steaming from our pores.

With our youthful energy

We hot-highway-determined

Pulled the ripe scent of the country

Into the hanging mouth of the city

Noon sun flooding the windshield.

We found the familiar Poolroom

But all friends had since moved away,

Those times left in the dusty stale air

And on the wide dark stairs.

New addresses, an old Italian barber

giving us directions (a hundred hands)

We found only empty warehouses,

The freight yard with

Its barren ghost noises

Tar stench

No one.

Thus hot and bare-chested

We drove past the city blocks

(Dark-skinned girls gleaming on the cement corners)

Listening to the wailing strains of Charlie Parker,

Rolling smokes, gunning up the highway

Under nameless signs, The humid afternoon

Blasting through the windows

Into our hair.

Then the sun settling, spinning itself

Into the dusk-black sands of Cape Cod.

First lights blinking on,

Blushing evening, brush-stroke moon.

Other friends found with lone payphone,

Hot coffee thoughts,

The last easy miles,

Grinning faces at the cambered porch,

The outstretched blue arms of the Atlantic.

Midnight we swam,

Salty, cold, naked, dangling,

We yelling into that huge caldron night,

The moon a perfect scratch in the blackened metal:

Silver, new, curled—and our voices

seasoning the mild ever-retreating air.

The morning opened

Hinged on the horizon of the ocean,

We followed the coastline north, uncomplaining

Hungry for every moment,

The small Porsche our home,

The glove box lid our table,

Eating powdered sugar donuts,

Splashing down sweating cartons

Of cold milk.

Kris, your straight nose in the sun,

Your hairless chest shining,

Your eyes licking the long green hills.

So the miles laid themselves short,

So we tore them off as if the road

Was a long strip of paper,

So we saw all the tanned faces

Followed all the trucks

Smelled the summer night deep

The silver ocean,

Rumbled by all the June days

Like a kick stone down a smooth hill.

II

That last night at Hal’s cabin,

We three rattled over dusty dirt roads

To the Spring Hill Diner.

And under the flickering neon,

We grumbled out of drunk night

To the bright white counter,

The wall menu, the thick cups of coffee.

Hal went to bed early that night

As he does often now:

His energy burning out early,

His poetry like a long-since-shaved beard,

Life hung across his strong shoulders

Like great flour sacks of earth,

His days hard beside an angry woman.

Yet still his eyes searched out

The fruit of the night

Its juice wetting his lips.

That last night, over the last beers,

Our words grafted us together;

The beer cold in the swooning June air,

Flies aiming for a hole in the sky.

And you—Kris

Your eagerness lighting in your smooth face,

Your ego like a draft,

Your lack of attachment supposedly a vision.

We slept on the cabin floor,

Morning the rooster woke us,

Hal rummaging back

Into the pattern of his days:

A clean shirt

His honest good-bye

A poet’s finesse

Still on his eyebrows,

Lost only

In an angry world.

Poem written in 1975

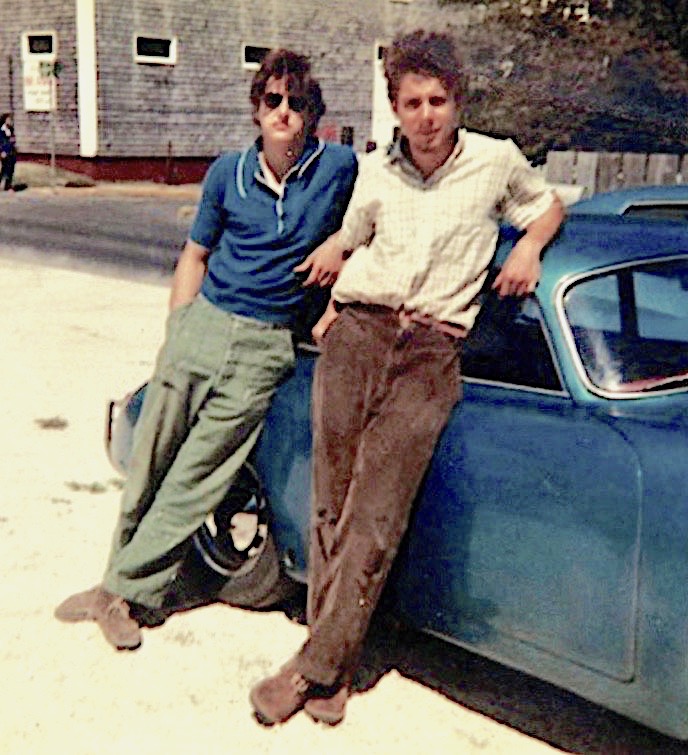

The photo above was taken by an English girl named Penelope. This was the morning after the night Kris spent hours trying to seduce her in a smoky gay bar in Provincetown, Massachusetts as I hustled pool making enough money for another week of driving around. Oddly, I ended up with Penelope that night. I did a painting of her later in the year when I was living in the Midwest.

I wrote this poem (below) on a typewriter in Montreal, the entire poem in one sitting, one finger, no mistakes. I still have the taped together manuscript. The poem was read on Corfu to two American girls on the beach as the sun set over the Aegean Sea and my nakedness and their nakedness caught the last light, my formidable erection dripping like a faucet. I was about to bed the nasty one with the wonderful breasts when my travel companion threw up all over us and my light cotton sleeping bag. Killed the moment. 15 miles of empty beach and he throws up on us!

TOUCH

Thousandth wielder at the ancient anvil

pounding at the cold metal of her heart.

I

That black night, came out of black hills

Tired headlights eyeing the endless road.

Quiet constant: vision of one slant pole

Curving white line into the damp fog.

Last midnight gas, tired old drunk filling the tank,

Push-started, our heads bouncing with beer.

The old Porsche grinding out the distance,

Hill curves out of Vermont,

Kris your head snapping back in sleep,

Bridge into New York State,

Rose dawn falling in a clouded Lake Champlain,

Earth smell, the last sip

In a broken Thermos of coffee.

That night I entered sweat-slick bare-chested,

A twice-read paperback of Burroughs in hand,

Read the part about words falling like dead birds

Into the street. Sober, I realized your nakedness

under the sheet, your red hair against the pillow,

Black eyes turned to the moon-flecked wall;

Out of the conscious quiet a dog bark.

Stiffening in the pants,

Tried to speak of why I hadn’t

That morning so hot, Wendy,

About wet last night,

Once on the floor hard,

Long, gentle, again on the sofa.

Vomited in the small bathroom,

Brushed my mouth out,

Peppermint soap and my finger,

Vomited the humid smoke-dull pub

Where I drunk stared at your tits taut in black,

Red hair over tight tight black.

Oh again made you,

Sweat in a pool

Slapping against you,

Your hands, fingers

Digging into my ass,

The smell sweet of your sex,

Morning, your sister seeing us together,

Naked, hopeless, sticky.

Again, the after-coffee highway,

Salvation alone.

II

That night too, moon hung,

Cold, icy, Wisconsin.

First time made you, Ann, in the blue snow.

Threw down my coat for your ass,

Obsessed, pulling down your frozen pants,

Pussy so hot, your pungent juices

Dripping on the leather of my jacket.

In shivering haste, fast, deep,

We laid in that wind-turned valley,

Wine tripping our brains,

Moon glaring in our eyes,

My hand feverishly gripping

Your small trembling breast.

Inside on the worn blue rug,

Skin tingling, naked

Wine clumsy, savage

Tongues reaching salty lemon.

And at late, your brother patting my ass

And drunkenly turning to his own image in sleep.

III

I fell to the western sky

Trying hard to create distance.

Motels, broken neon, lone grain elevators,

Dirt-front gas stations, spicy pie, dank mornings,

All-night Cafes, hail storms at horizon, hitchhikers heading,

Curly black hair on the bedsheets, long pipe smokes,

Damp March cold creeping from all cracks,

And you, Lisa, in flannel.

Night of touch tender,

The curve of your back

Lifting my hand fanning over

Cheeks of white flesh, yearning;

Sleep glazed, pressing my hard penis

Into those cheeks hoping you would turn.

Morning kept stretching further,

You reaching in my sleep,

All dreams, all intentions.

And last, you crawling back into bed,

Smelling slightly of toothpaste,

With two steaming Styrofoam cups of black coffee.

IV

Andrea, your lips a final warning,

It was at Grand Central Station,

Your eyes, hating, hopeless,

Left me, numb, walking. At long last

Tears clearing away all pretensions,

Lovely pure naked hurt

Pitifully tearing away inside,

Open sobs weakening like rising mist

Passing into the dark sooty streets.

And you, Andrea, lost in the fluorescent hole

Of the Holland Tunnel; only in memory

You choking on my come, staining brown sheets,

One sunny Sunday morning.

Long night, behind a long photo of Rome,

Espresso wakeful, rolling fat cigarettes,

Romantic broken-hearted gloom on mouth edges,

Eyelids dark, thick, tear lines in dirty face,

Rich coffee odor, white table cloths, red roses,

Old violinist spilling songs–you were there

Suddenly, alone, Louise.

Lost talk drifting into the narrow street,

The taxi draining out cold December limbs,

Glancing eyes, black brows, deserted Park Ave.

I showered in your fancy apartment,

Inspected my face in the clouded mirror,

And then, door ajar, steam and me towel-clothed

Penis bulging, moving toward you on the bed.

Sangria on ice and the post-late-show mounting

Of your craving body.

Dancing in your darkened room,

New York City out the window,

Last lights fading in your hair,

Dancing tensely careful

My penis in your moist center

For the last time.

Rainy December morning,

Down into the subway

I stand gladly alone

Filled with coffee and waffles,

The slapping rain no longer audible

Against the approaching train

Crashing out of the black.

V

Stef you saved me twice.

Always can hear the voice of your horn

Melting into the gold evening river,

Laying notes over the green ripples,

The ripe scent of late summer,

The garbled talk of the autumn rapids.

Still see you sauntering drunk

Out of the broken end of the big room.

Seen you all seasons–quiet, alive.

Pipes hanging, we molded sanity,

Blew smoke rings, savored toasted corn muffins,

Beans and brown rice. Evenings there was

Jazz, drip-ground coffee, Bass ale,

Slowly coloring meerschaum.

All moments, All visions,

The silent destiny of nothing,

Our own image in the shop windows.

Written in 1975

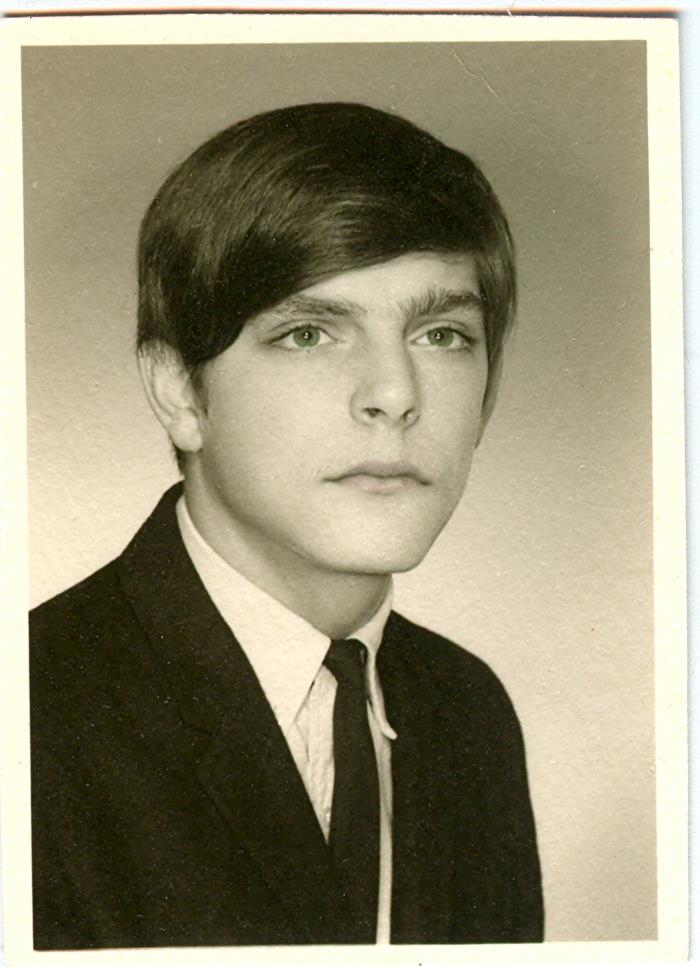

Eric Green attempts to channel James Dean in 1976, northern Vermont; Marshall Green behind with the grimace. JD died 61 years ago September 30th. I raised a glass at 5:15 California time just as I do every year. Words fail me. Yup. Even me.

Do these work?