Cleopatra

A VACATION

The boy hadn’t been right for days. Even after they left the mountains behind, Route 2 now joining the railroad and the river through miles of birches, he was miserable. And he usually loved that section of highway, the white bark of all those ancient trunks. No matter where his family moved, once a year that stretch of road meant the start of vacation. As his father guided the sputtering Volkswagen Beetle, the August sun flashed between trees across the windshield. Any of this would’ve normally cheered him up, but even when his father’s face appeared in the rearview mirror and winked, the boy didn’t smile back.

“Delaney’s, Boo,” his father said, inhaling a Camel. “We’re going to watch lobster boats. I know that much. Tomorrow morning those lads’ll be pulling traps right below us.” His father was obsessed with boats, having dragged the family to every boatyard in Maine on each vacation. Years of it and still no boat.

“It’s good the rain has stopped. A perfect day now,” said his mother in her clipped way. But it wasn’t perfect.

Five months ago the family had moved to yet another new town. If it was in northern New England and had a mill, they’d probably lived there, but this time they’d gone west to upstate New York. The boy had joined the fifth grade in the last half of the year and was having trouble making friends. There were a number of problems as far as he could see: His family didn’t own a TV or a new late-sixties American-made car with a chrome grin, they’d rented the only house in the neighborhood left over from before the development, and then some of the kids had overheard his mother speaking what they thought was German. She was actually Swiss, but he knew it was useless attempting to explain that.

“He’s a kraut. Spazo’s a kraut!” This from Joey Ligamori. Joey, famous for having masturbated a dog, was the ringleader at the school bus stop, and every morning there was some new torture waiting. His books had been tossed into trees or puddles, he’d been tripped into dog shit, tied up with clothes line so he missed the bus and been forced to walk to school though he’d run most of the way. Over an hour late, he hadn’t bothered to offer an excuse to the principal. He’d received detention and a note that required signing by his dad.

“Why were you so late, Boo?”

“Missed the bus.”

“How’d you miss the bus?”

“Just missed it, I guess.”

“That ain’t the truth though, is it?”

He shook his head.

“I think you should tell me.”

He told. His dad rubbed his unshaved jaw a few times and nodded sagely, chewed on the fingernails of the hand holding his cigarette, smoke wreathing his handsome face. “New guy always has trouble, has to earn his wings. Just go up to the biggest bully and punch him in the nose. Works every time.”

He’d need a footstool to hit Joey Ligamori in the nose. It was fine advice for a six-foot factory worker with biceps like footballs, but he couldn’t imagine his little fists doing anything but bouncing off Joey Ligamori’s big belly. And then that summer fresh trouble had arrived.

In New Hampshire he’d fished or played ball with his friends, but these guys collected GI Joes. It was the first he’d heard of such a thing, and it made no sense to him; nevertheless, he wanted to belong. A week before the family had left on the vacation, Joey had approached him with the usual scorn and shove. But after he’d picked himself off the ground, Joey’d said, “If you wanna prove you’re not a goddamn kraut, you better get a GI Joe.” He’d raced home to tell his mom the news: all he had to do was get one of these toys and they’d accept him. Then maybe the looming school year wouldn’t be as terrible. But he’d been worried, knowing how his mom could be. She had disdain for so much he thought was okay.

“I will not have my son playing with soldiers,” she’d said.

“But, mom, it’s just a toy.”

“It is a soldier and that is glorifying killing.”

“It’s not real,” he’d said quietly. “It’s plastic.”

“Will, I’m sorry, but I can not have it and that’s the end of the matter.”

The next morning he’d walked to town and priced the dolls, realized they were out of reach. He’d considered stealing one, but they came in boxes with clear plastic windows, too big to slip under a shirt or into a jacket. That evening he’d talked to his father. “Ten bucks for that stupid damn thing. Come on, Boo, you’re smarter than that.” Two days later he was in the backseat of the car, crammed in with luggage, and he was still angry with his parents. What did they know about being tortured?

His father swerved the Volkswagen toward a gas station and country store. “Why are you stopping now?” said his mother, her delicate features in profile for a moment.

“Won’t be a minute.” The ratchet sound of the hand brake.

“Harold, it is not even noon yet.”

“Won’t be a minute, honey.” He lumbered across the dirt, his work boots raising dust with each step.

Soon the car was headed east again. His father lifted the quart of beer from his crotch, took a long pull.

“Boo, this is Ballantine’s ale. Best stuff ever brewed in this country.”

“Do not be telling the boy about beer.”

“Ain’t nothing wrong with beer, nothing at all.” He drained two more inches, the bubbles rising madly, then settled the damp bottle between his legs again.

“You know what I’m talking about.” She said it nastily.

“That what they teach you that in that special watercolor class?”

Her body stiffened, and he snapped open a steel Zippo and fired a cigarette, exhaled, the smoke collecting in the backseat though both rear wings were angled open.

About every three-quarters of an hour the Volkswagen nosed toward a store. Though the highway was only occasionally slowed by a town, his dad seemed to have a special sense for where the cold ale was. Once he was forced to drink a Schlitz.

“Not a bad beer, Boo, but not the greatest either. Always drink the best you can get. That’s my motto.” Another wink.

“Harold, please.”

“What’s all this? It’s my vacation and you better believe I’m gonna enjoy it. You two are both too gloomy. Cheer up for God’s sake. This is a reward for working all year, not a bloody funeral.”

On the fifth beer they arrived at Delaney’s Cabins. His father retrieved the key from the office; a young blonde woman in a tight summer dress followed him outside laughing. His mother watched, and though he couldn’t see her face, he felt her disapproval. When his father touched the young woman’s arm, he glanced over at the car and smirked. Soon the Volkswagen was careening down the gravel road between pine woods. They had stayed at the same cabin as long as he could remember, the end one in the row of five, at the cliff’s edge, overlooking Penobscot Bay. At the sight of the ocean his mood slowly dissolved. Something about the distance and the pure color seemed to drain everything else from his mind.

They parked beside the white cabin, its paint as scaly as their rented house, which seemed so far away now. His dad popped the Volkswagen’s front bonnet and set a plaid suitcase on the grass. “I’ll bring in the bags. You two go ahead down to the water.”

His mother turned to his father.

“I’ll be down there in a minute.” He sucked smoke from the Camel as she said nothing. “Don’t worry so damn much. At least I ain’t taking any four-hour watercolor classes.” With that his mother walked across the lawn toward the sea. “Come on, honey, I shouldn’t’ve said that,” he called after her. “This is supposed to be our vacation—let’s enjoy it.” But his mother didn’t turn back. His dad retrieved the luggage from the backseat, picked up the plaid bag, and headed into the cabin, somehow balancing everything.

Now that his father was gone, his mom returned and sat down at the rickety picnic table near the car. “We should take off our shoes first,” she said. “We will only get sand in them.” He sat beside her and unlaced his sneakers, set them carefully on the seat, his socks balled up inside. He knew she liked things neat. Then he walked behind her along the grassy edge of the road and onto the narrow path that led through the woods to the sea. Every year, when he was alone, he would force himself to run along this gravel road, his feet screaming because of the sharp pebbles, then onto the mud path, smoother but still hot from the sun, and finally onto the moss in the dark part of the woods, so cool and soft on his tortured soles.

Two-dozen wooden steps teetered steeply to the rocky beach below them. A hand-lettered sign mounted on the end post: Use at your risk. “Be careful,” his mother said. “Hold the railing tightly. These stairs are very slippery and dangerous.” It was the same warning every year, but somehow it cheered him to hear it again. She said so little that he listened to everything with care.

He stepped along rocks which gradually became smaller until he stood on the narrow crescent of sandy beach with the icy tide nipping his feet, his mother just behind him at the edge of the water. She didn’t like to get her feet wet. There was that smell of brine and freshness touched with seaweed in the sun, a smell that made him feel as if he’d never really breathed air before. He heard the high-pitched complaint of a gull and glanced up. Suddenly the threat of Joey Ligamori and GI Joe no longer seemed real. This was real. This immense shout of perfect blue sky and water vibrating at so straight a line. He turned to his mom. He wanted to say something, to explain. Instead he smiled, and she reached forward and rumpled his hair. It felt strange; she rarely touched him. He just wished that she would feel what he was feeling. Just once.

After an hour, the sun was lost in the pines and the beach had turned cold. He could tell his mother was nervous. “Your father is not coming. We better go back,” she said, and gathered up the few stones and bits of driftwood they’d found, cradling them in her untucked blouse. They trudged up the steep steps. She always looked so skinny to him, and he worried he would never grow to his father’s size. As if sensing this, his dad occasionally sneaked them out of the house when his mother was resting, and drove them to a diner or hot dog stand, once even ordering two foot-long chilidogs. His mother didn’t believe in eating meat. Her fine black hair, pale skin, and almost black eyes were his as well and he envied his dad’s ruddiness, green eyes, and sandy mop. Then he could’ve crushed Joey Ligamori with a single blow.

The path through the woods was eerie without sunlight, and he glanced over at her. She clutched the gathered bits to her frail chest, awkwardly plodding along. With a rush of tenderness, he reached for her free hand. The hell with soldiers and Joey Ligamori. Besides, the watercolor of flowers she had been working on was lovely, so precise, each bloom and leaf carefully finished before beginning the next one marked out in pencil. She’d begun taking the classes a few months ago, surprising him because she’d never done anything like that before, preferring to stay inside whatever house or apartment they lived in. She dropped his hand after only a moment, saying nothing.

At the cabin they couldn’t get in. The door was latched. His mother called through the dark screen. Nothing. She pounded. They circled the dusky cabin, yelling his father’s name through every window. At the one on the far corner next to the cliff, he heard something and looked in. A body snored, sprawled on top of the flowered bedspread, a bottle of whiskey half empty on the nightstand.

His mom decided on the car horn, beeping intermittently at first, then just holding it. Three or four vacationers left their cheerfully lit cabins and appeared in the twilight like zombies. Finally, his dad, hair standing straight up, let them in with a crooked smile.

In the morning they sat out on the back steps and watched the lobster boats.

“Look at that sun, Boo. Like a million sparklers going off on the Fourth. We’re lucky to have weather like this.” The coffee cup only chattered slightly as he lifted it off the saucer. He drew hungrily at his cigarette, exhaled toward the sea. “Someday we’ll get a boat. The hell with the mills. The mills eat a man alive. You and me, Boo, we’ll be out there, fishing together every day, pulling traps. That’ll be the stuff, eh?”

He grinned at his dad. He’d heard it every year.

That evening they went to the docks. He wore a clean sweatshirt, the cool cotton soothing against his sunburned skin. His mother said she’d stay in the car, she was tired from the sun. Huge boats hammocked by wide straps hung in the air supported by steel trolleys. Masts and spars, sanded and awaiting varnish, rested on saw horses; other craft balanced on their keels buttressed by thin rusty poles with flat ends. “A yawl, Boo. That one’s a yawl. Look at those lines, eh? See, the rudderpost is before the mast. A ketch, the helm would be behind the rear mast, like a schooner. But we don’t want a fancy boat like that. Too much upkeep and no good for fishing. Just an old lobster boat with a strong diesel is all we need, right?” His dad squeezed his sunburned shoulder and he tried not to wince. “It won’t be long now, you wait and see.”

His dad gave him a dime for the pop machine that stood on the wharf. He opened the narrow glass door and couldn’t decide what he wanted to drink. He slotted his coin, and gripping both a root beer and an orange crush by the neck, he allowed fate to make the decision. He pulled. Both jammed. He tried again several times, but got nothing. He couldn’t ask his dad for another coin.

They went to the restaurant where they always had their one special dinner out. His mother ate raw oysters, one of her rare extravagances. “It is only for once a year,” she said, and stared at the six shells resting on cracked ice with their pallid cargo, which to him just looked slimy. He knew his dad didn’t think much of them either, since he’d never try them. His mother had long given up asking. “As a girl I ate them with my father before the war. My father knew a lot about oysters. He was educated in so many things.” She always said this as she carefully trickled the lemon on each one. It was one of the few times she ever seemed truly happy. And with a relish he envied, she slid them into her mouth. He wished she’d feel, just once, that way about him.

The next day it rained, and after a cold, wet morning at the boatyards, his father sat at the cabin’s tiny dinette table. A forest of empty Ballantine’s in gold cans, an oversized clamshell ashtray, his attention glued to the foggy drizzle collecting in droplets on the screen, the cabin heater humming, the chime of the bell buoy. His mother read from a paperback novel, then The New Yorker, looking up annoyed the few times he tried to talk to her. He asked her if maybe she was going to work on a new watercolor, and she shook her head. “I left my materials at home,” she said.

In the late afternoon the rain stopped and he left them and headed along the gravel road, up the hill to the motel’s office. At first he was too shy to enter, but eventually he pushed open the screen door and immediately, intently, examined the rack of postcards, the assortment of gum and Lifesavers, unable to answer the young blonde woman’s questions with more than a mumble. Every time he glanced at her he could feel himself redden, but his eyes couldn’t stay away for long. Then she disappeared, telling him to wait. When she returned she handed him a thick slice of freshly baked banana bread with butter. “I’ve never tried it before,” he managed to tell her. “Oh, I think you’ll like it,” she said. He couldn’t imagine how you could make bread out of bananas. As he walked back through the blue dusk to the cabin he ate the moist warm bread with the cool sweet butter. He thought it was the best thing he’d ever tasted.

The following morning it was foggy again, but by noon the horizon emerged like a magician’s trick. As they walked the path to the sea, the woods dripped and there was a delicate tapping on leaves. The three of them settled at the beach on a massive boulder which had been carved by the tide to resemble a bench. His mom passed around thin cheese sandwiches with only a smear of yellow mustard on white bread. They were cut on a diagonal forming triangles, his father insisting on that.

Every hour his dad sent him back to the cabin for another beer. “Always drink it icy cold if you can,” was his advice. Once as he returned, carefully carrying the damp bottle, he overheard his father say, “But what kinda class is that with a teacher like that? Negros can’t know nothing about watercolors or art. Honey, sometimes I think you don’t think things out.”

Toward late afternoon he said, “Boo, I think it’s time for my swim.” He only went in once a year. Removing his boots first, he took his swim trunks and disappeared behind the boulder, then reappeared, stepping gingerly, his skinny legs bone white below the muscled sunburned torso. He lit a Camel and moved cautiously over the loose rocks to the sandy horseshoe of beach, waded slowly into the ocean. When he was in up to his chest, he let out a startled cry, and down he went, the cigarette left floating on the surface of the water. His mother jerked to her feet. “Harold?” she yelled. They both knew he couldn’t swim. She cried out again. Then his dad came up sputtering, and like someone shot in the leg, dragged himself to the rock bench. His mother spent the next hour patiently extracting sea-urchin quills out of the ball of his foot with her eyebrow tweezers. His dad grimaced and worked at a beer.

He awoke in the middle of the night. His father was snoring and he wondered if his mother was asleep. You could never tell with her. His parents had taken the two tiny bedrooms and he a cot in the main room. They didn’t sleep together, his mother had explained, because of his father’s snoring. Slipping out from under the itchy wool blanket into the darkness, he crept to the screen door.

Outside it was only stars, pine tree tops in black silhouette. A cool breeze drifted in from over the cliff. He felt his way with bare feet over the gravel along the dirt to the moss where some of the day’s heat miraculously remained. After a while he pulled off his underwear and lay there, wanting to absorb the softness through all his skin. His mind drifted and the young woman from the office was with him. His center lengthened and swelled. He tried to keep his hands away—his mother had told him how wrong it was. But the ache was overwhelming and he had to stand.

At the steps he carefully let himself down, the sand slippery between his soles and the rough wood. Across the loose rocks to the beach. The black ocean lapped over his feet as he inched in deeper and deeper, worried he might step on a sea urchin and go down. He shivered as he stared up into the heavens, the dizzying swathe of the Milky Way like an ancient wisdom. It looked so close, but he knew how far away it all really was. He thought of her again, the fullness of her chest in the printed dress, and reached for himself, the icy water just below his hand. He stroked, tears spilling down his cheeks. At his moment he thought he would hear a sound, a splash, something. But there was nothing but an intensely pleasurable burning sensation as he almost fell into the water.

The next morning it was over. His dad placed the bags back in the car and they drove slowly up the gravel road to the office. No sign of the young woman as his father paid the bill. He was relieved, fearing that on seeing his face she might know something. Soon they were on their way home. A last glimpse of ocean, past the white trunks of the birches, through the mountains, his dad not stopping for anything, not even beer, until they got well into Vermont.

Outside Burlington, they visited a surplus store his dad favored for work clothes. His mother still in the car, he waited as his father tried on a heavy canvas mustard-colored jacket; “Carhartt, Boo. Always buy the best if you can.” While his dad tried on boots, he wandered up and down the aisles and came upon a bin at the back of the store. It was full of GI Joes, perhaps a hundred of them. He couldn’t believe it! No boxes, no accessories, just the dolls dressed in their green army uniforms, all jammed together as if in a mass grave. The sign on the bin read: Sale, any one $1.

He raced over to his father. “Dad!” He grabbed him by the arm. “Dad, I got to show you something.”

This time when his father winked in the rearview mirror, he smiled back.

“Great vacation, wasn’t it, Boo? The best ever, eh?”

He nodded, their secret safe. Actually, his father had been almost eager to buy it for him, which made no sense.

They drove over the top of Lake Champlain, paid the toll at the bridge into New York State, and before too long pulled up in front of the rental house.

Once the bags were unloaded and his mother had disappeared into her bedroom, his dad handed him the package. He ran over to Joey Ligamori’s. He stood a moment in front of the new split level, before the golden door with the three oddly shaped windows, his heart pounding. Finally he pressed the bell. It rang with a fancy kind of multi-note chime he’d never heard before. Joey’s mom answered and left him standing on the steps as she turned to call for her son. When the big kid appeared he didn’t seem to recognize him for a second, just stood there holding the door cracked until he said:

“Oh, Spazo, it’s you. What d’ya want?”

He held out the bag like an offering. “I got a GI Joe.”

“‘Bout time. Let’s see it.” Joey came out on the steps and grabbed it. He unrolled the bag and shook the toy soldier into his hand. He stared in disbelief, then he started laughing and slapping his leg.

“Spazo, this is a nigger GI Joe. What the hell is wrong with you?” Joey dropped it onto the steps where it rolled over and lay brown face up on the new cement. He turned in disgust and went back into the house. The door slammed.

He picked up the scuffed doll and walked home. The house was quiet. His mother was probably in her room as usual, and his dad was drinking beer at the kitchen table; there was the haze of cigarette smoke in the doorway and the clink of a bottle. He headed down the dark hall for his room, his mind in complete confusion. Suddenly, the doll was snatched from his hand. He turned, alarmed.

“What is this?” she said.

He stared.

“Will, where did this come from?”

“I don’t know,” he mumbled.

“Did your father buy it for you?”

“Mom, it’s only—”

“I know what it is. I can see what it is.” There were tears in her dark eyes now.

His father walked into the hall, his cigarette in at his side. “I bought that for the boy.”

“How could you?”

“How the fuck could you?” He was yelling.

“Harold, he is French. He is from Paris. He worked at the Louvre for nine years before moving here. There was nothing dirty or whatever you are thinking, but what would you know about culture or real tenderness?” She slid slowly to the floor and just sat there, crying, cradling the doll in her hand.

He looked at them, his parents, one red with anger and frustration, one a bundle of misery, and then he said something that neither of them heard.

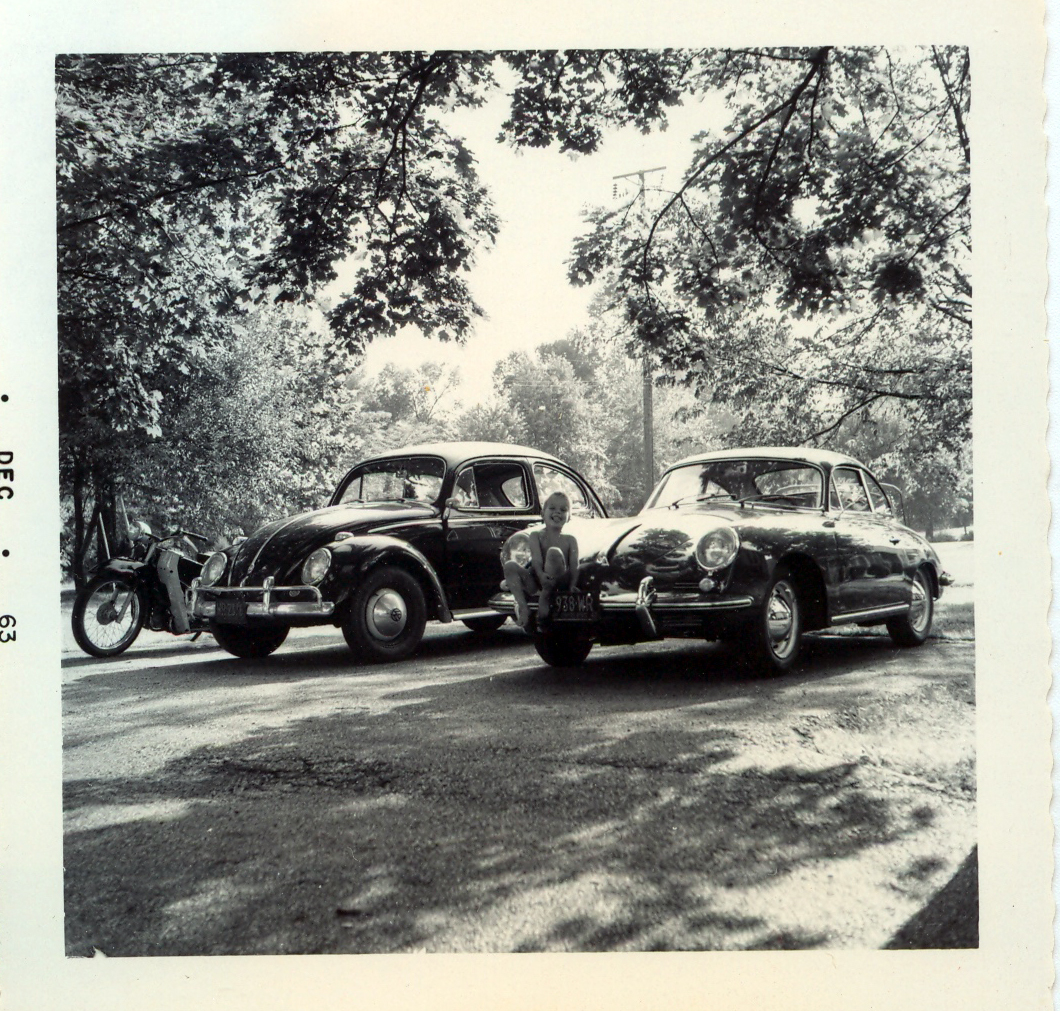

The author in 1963