FRANK, FRIENDSHIP, AND THE HANGING SCAFFOLD

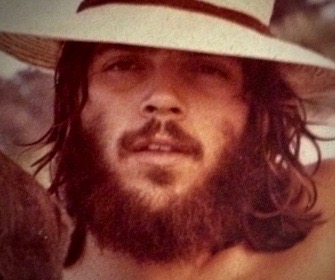

An e-mail arrived the other day from a woman I haven’t seen in almost 30 years, and it put tears in my eyes. We’ve stayed in touch on occasion because during my early 20s I worked for her husband. Frank was Italian American, from the Jersey shore, and at that point in my life I’d never met anyone like him. He had quite an effect on me over the four years we painted houses together. When he returned to New Jersey with his family, I waited for my career to take off before looking him up again. But he died before that could happen.

The paint crew Frank assembled in Vermont during the late 1970s was unusual. Two members had PhDs in art and philosophy, a couple shook from hangovers every morning, one Vietnam vet could move a 40-foot ladder like it was a toothpick, and one never finished high school and had no fear of heights. That was me.

When I first met Frank I thought he was a big friendly guy who was overweight with a face as pretty as a choir boy. Then one day on the job site, a cruel, tattooed biker carpenter with biceps like footballs started taunting Frank. Frank took it in stride for about ten minutes. Then he said, “If I hear one more word outa you, I’m getting down off this ladder.”

This stunned me coming from Frank. He was usually so easygoing if not actually sweet. If he noticed someone who appeared down and out, he would walk over and say, “Waddya need, a couple bucks or something, buddy?” and pull out his roll of bills.

The carpenter made another nasty remark, and Frank calmly set aside his brush and paint. When he approached the carpenter, the guy immediately took a couple violent swings at him. With startling quickness, Frank stepped around the punches and hit the guy in the face maybe four times with only his open hands. The blows stunned the carpenter; he staggered back and slumped to the ground, his face a livid red. Frank surprised me again when he said, “Are you okay, buddy? Come on, talk ta me,” and extended his hand to help him up. I saw then that Frank had hands the size of pie plates.

After that I asked Frank to teach me to box, and I began to notice the style with which he handled many situations. Though only a half dozen years older, he seemed to know about the things I didn’t, and he began cautiously to give me advice like an older brother. Back then my dress shoes were hand-me-down Wallabees from my father. One evening after work when we were headed out drinking, Frank looked at my feet, shook his head in despair, and said, “Green Bean, take off your shoes for a minute.”

I stared at Frank: ” On the street here, you want me to take off my shoes?”

He nodded, “Just for a second. I gotta see something.” So, I took off my shoes and handed them to Frank. He promptly threw them into the Winoski River which was channeled like a canal through Montpelier. I was shocked, but Frank put his arm around me and we walked to the shoe store down the block. He bought me new socks as well, and as I was being fitted (bone colored wingtips) he explained what a shoe was. He told me how his father, a gambler in Atlantic City, had his little toes amputated so he could wear a pointier shoe without annoyance. I wish Frank could see my collection of Italian dress shoes now, particularly my black snakeskin loafers.

Frank managed to get the job painting a number of downtown buildings in Montpelier, Vermont. In order to paint a five or six-story building, we needed a hanging scaffold. This is a platform with two winches that raise and lower the base on metal cable. Two large iron hooks are aligned near the edge of the roof, and the cables dangle from these down to the platform.

Frank rented the rig from a guy called Crazy Louie, and one morning he asked me to try it out with him. Crazy Louie had three teeth and wore white plastic loafers with a gold clasps. The hanging scaffold looked as if it had been used to paint the Coliseum in 80 AD. Frank asked Louie where the safety harnesses were, and Louie laughed. “You don’t need them,” he called back over his shoulder as he shuffled off. “I ain’t never used one. They’d juss get in your way.”

Frank and I looked at each other, shrugged, and started cranking the wooden platform up the side of the five-story building that was eventually to hold the New England Culinary Institute. At about three stories, Frank glanced over and asked how I felt. “Great,” I said. “You?”

“You can’t touch the building.” This was true. If you reached out for the bricks to steady yourself, the platform swung away and you felt yourself being sucked into the void. Frank’s voice sounded a bit nervous, and I secretly enjoyed this since he seemed to be fearless about most everything.

As we reached the five-story mark, near the cornice, I looked up. The cable, about the diameter of a pencil, was badly frayed at the juncture with the iron hook. I heard Crazy Louie laugh. I thought of Frank’s 225 pounds. At that instant the cable slipped on the reel and the platform jerked down about an inch. Silence.

“You okay?” Frank said in a strained voice.

“I can’t move. I seem to be frozen.” I hated to admit this but it was true.

“I can’t move either. Is mosta your cable all bristled and busted?”

I nodded slowly, unable to take my eyes off the remaining dozen threads that supported us. “What’re we going to do?”

“I’m gonna talk us down, okay?”

It took a while, but eventually, each coaxing the other, very gingerly we managed to winch ourselves back to the pavement. The ground felt amazing. We knew we’d almost died together, and that’s a bond, believe me. Frank took me directly to a bar and bought us two cognacs. A machine shop replaced the cables the next day.

We’ve all had friends like this, those who have truly touched us, changed our lives, been an influential component in our formative experience. There were even times when I found myself saying, “What, you wanna cup a coffee or something?” in his voice. I always figured Frank and I would hang out together when we were middle-aged, mulling over all the things we’d done. Before Frank died, he owned an Italian restaurant in New Jersey, and he’d telephone and tell me stories about Sinatra, Joe Pesci, and Mickey Rourke, who all ate his food. “Come on down and see me, Green Bean,” he’d say. “I’ll fix you the best dinner you ever ate.”

How I would love to have that option now. To once again hear Frank sing “Under the Boardwalk” or imitate De Niro in Raging Bull, both which he performed perfectly. It’s a mistake to put off for too long visiting those who have meant a lot in our lives. It’s easy to find excuses for not making the effort, but when it’s too late, the chance is gone forever.

And his wife’s e-mail that put tears in my eyes? She wrote how her son, Frank’s son, whom I knew as a young boy, cooked a fantastic meal at the same Italian restaurant this Thanksgiving. He served the feast to 300 homeless people in a fire station where long tables had been set up. She wrote that everyone had a wonderful time, and asked me when I was coming down to visit.

Love you, Frank.