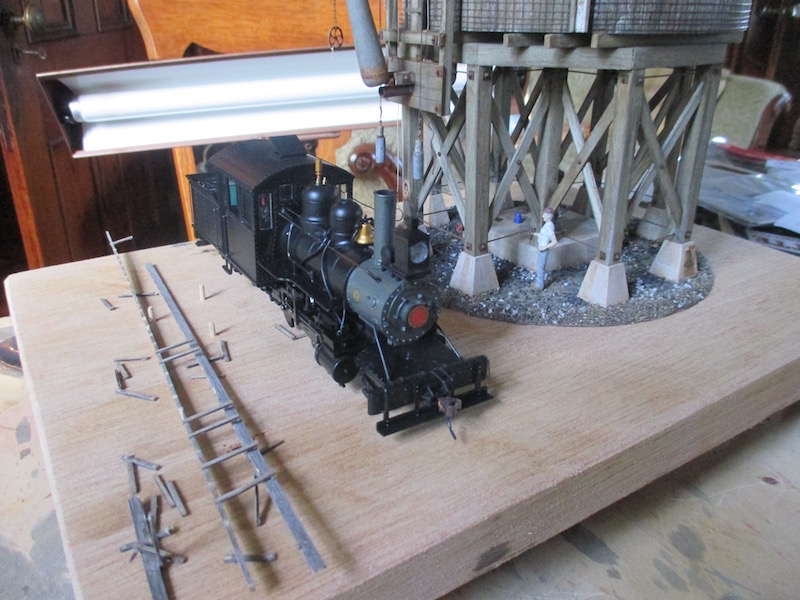

The O-scale water tower under construction with a Lee Turner plow on the right. Turnerize: to transform average O-scale model railroad products into steam era masterpieces.

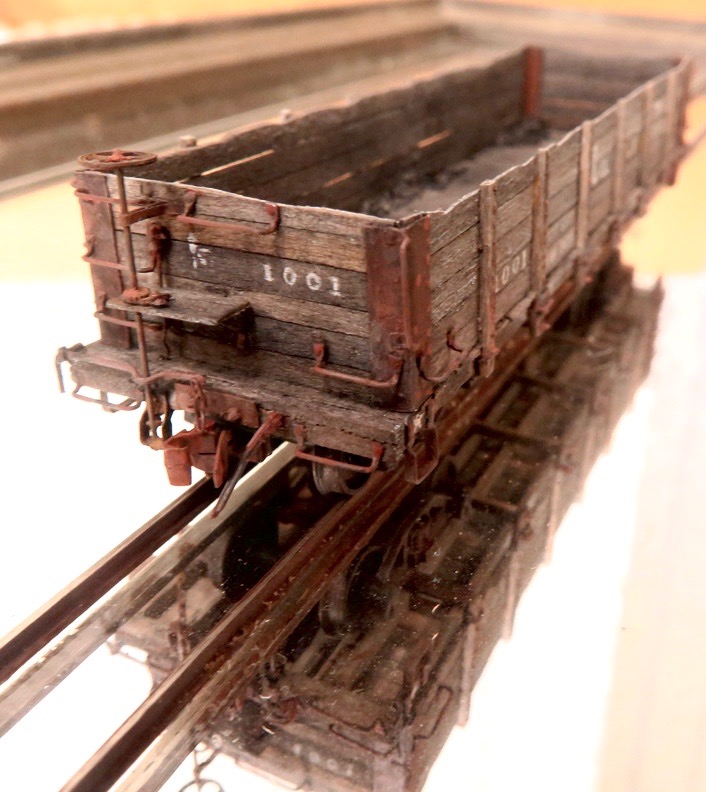

Tower and gondola car just a few days before the contest. Note coin for size.

When I was a teenager, I entered a model railroad competition at the encouragement of my father. It turned out to be an exceedingly positive experience, one I’ve relished over the years since my father died shortly after, and it was one of the nicest times we would ever spend together.

To read the previous column: http://www.penbaypilot.com/article/eric-green-fathers-wing-foils-and-model-contests/48069

40 years later, I recently entered another such competition. The outcome, however, was almost the inverse.

My good friend Dennis Brennan http://www.brennansmodelrr.com a noted and famous model railroader flew out from Missouri so that we could attend the 36th National Narrow Gauge Convention together. Dennis is the only person I’ve ever known who is always happy. I’ve never understood this. I can call him at any time of the morning, really early including the one hour difference, and he’s consistently almost annoyingly perky. But we had never spent time together. This was a full week.

I had been building an O-scale water tower over the past month, working intently every day. I was very proud of my tank with its peeling paint and weathered wood support structure, not to mention its iron-banded roof. My cut man Lee Turner—who was offering tips based on extensive photographic documentation—was truly impressed. Lee Turner might be the finest O-scale modeler on the planet. My friend Earle Mitchell, whose ancestor had been the 14-year old cabin boy on the Mayflower, had even written a story utilizing his grandfather’s character about the creation of the tower, giving it narrative reality. I would slay them dead at the contest, these narrow gauge snobs. They were coming to Maine, my home turf, where I would be victorious again, same as in 1979, this outing kinda for the memory of my dad.

So . . . things were looking good! Lee was heaping praises, Dennis was flying in as backup.

I even refinished two models from the same batch that had won multiple blue ribbons in 1979 in the NMRA convention in Granby, Quebec. How could I miss? Three beautiful models, two proven winners!

First, I took a wrong turn picking up Dennis at the Bangor Airport. Ouch! I ended up in freaking Brewer during noon rush hour. Let me tell you—ain’t no rush around there at all, just a lot of potholes and pottier drivers. But, I salvage my reputation by buying Dennis lunch at Dysart’s truck stop—Still wonderfully the same and good.

Dennis is almost a perfect match for the Green household. His Irish half appeals to me, and his Greek half clicks with my wife, kinda like Domino slats where one Domino mates perfectly with two other halves. What I hadn’t reckoned on was Dennis’s drinking—likely from the Irish side. Now, the guy only stands about 5’ 3 1/2” in lift shoes, but this guy could probably fell Andre the Giant in a drinking contest. Maybe that’s why he’s always so happy?

Our first morning together, after an evening where I collapsed at around 9 p.m. and Dennis continued on with my wife, talking and drinking wine and Metaxa until midnight, he popped into the kitchen, all happy at about 6:30 a.m. It was a huge day for me, my water tower model needed finishing, and both tiny HOn3 cars needed air hoses applied, weathered, etc. I was tense, had a wicked hangover after matching Dennis beer for beer all the previous afternoon. Dennis kept telling me, “It’s all good,” a phrase I particularly dislike. “No it isn’t all flocking good, Dennis.”

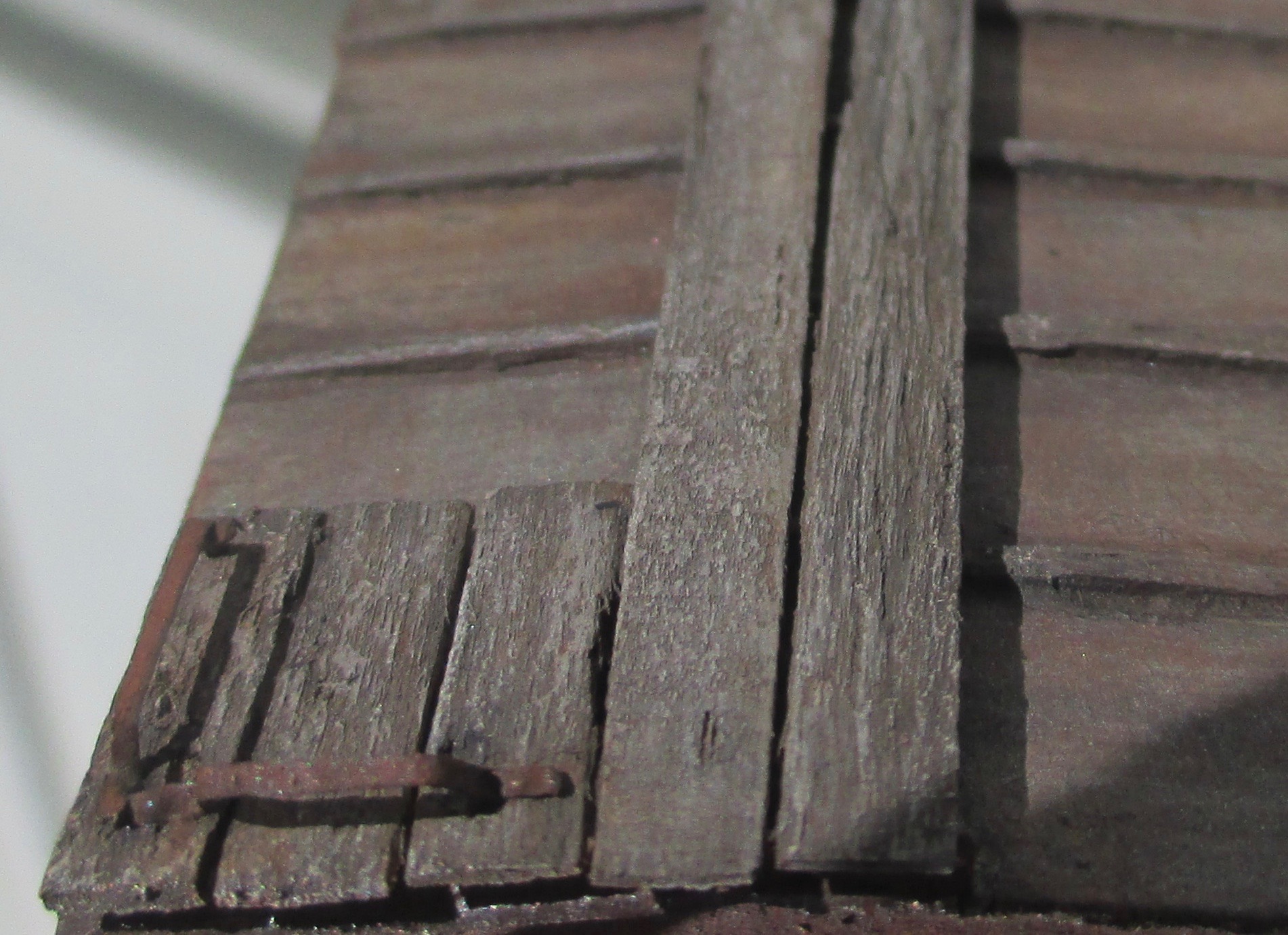

The HOn3 gondola car with air hoses attached above and missing below. The whole car isn’t much bigger than a large thumb. Almost everything was made out of either balsa wood, paper, or wire. 1980, refinished 2016. It’s even hand-lettered.

I kicked him out of the work room twice when things went wrong, but everything seemed puffy and roses soon enough as the three models were completed by noon, which gave us a couple extra hours to get to the contest in Augusta. I cracked a frosty, grinned at Dennis, and then proceeded to knock the entire delicate working spout mechanism that I was so proud of off the water tank.

Crisis! Running out of time. Wouldn’t have been so terrible if I hadn’t, in my haste, AC glued the darn thing back on crooked. Now the tower was in intensive care, and the doctor was losing it. I was sick of staring blind through an Opti-viewer attempting to align miniatures far too small for human hands. It had been an entire month of this lunacy; I was burned out!

The spout mechanism actually works (seen in lower photo) because I cast counter weights from hot lead to balance the heavy brass spout. The ring is to activate the water release valve.

We made the contest that afternoon with about ten minutes to spare, this after needing to sign in downstairs at the huge convention center and both being required to shell out 115 dollars. I’m still completely unclear what that 115 dollars was for? For the privilege of hanging out with some of the most dour, unpleasant, unhappy, ugly, slovenly dressed, and clinically morose old men on the planet?

The contest director, Bob, took an immediate dislike for me. Cowboy hat? Models too good? The other guy running the contest, Greg, was either dead drunk or had just had a severe stroke. Either impediment being a perfect choice to handle delicate models that fanatics had labored months over. He kept trying to grab my insanely tiny 40-year-old balsawood and paper gondola as he slurred and drooled at me. I kept batting his hand away as Bob explained how many rules I had broken. Looking back, maybe Greg was trying to tease me? Of course they disallowed Mitch’s wonderful story about the water tower [story below]. The tower doesn’t make sense without the story, but arguing with Bob only delights him. I do not enjoy delighting Bob. I do not enjoy anything about Bob.

So, contest entered, next day, we motored into Augusta in the 1966 Chevrolet Impala, my wife onboard, looking stunning and lovely as usual. I told her to tell the contest lads she was just my girlfriend, and sure enough, the old coots immediately attempted to flirt and pick her up. Quite the professionals! I was also asked to remove a small plywood board with some track attached, which I’d hoped to place under my E.B.T. boxcar. This broke the rules. The fact that the guy next to me had his model resting on a gorgeous furniture-quality rectangle of sceniced landscape was ignored. I mean his caboose on display rose off the table about eight or ten inches above my puny boxcar, lovely with its lacquered mahogany base, perfectly executed narrow gauge rail and hand split ties, etc. Still can’t explain that one. Note many things remain mysterious.

The tiny E.B.T boxcar. Every year “Friends of the East Broad Top” give an award. Since only one other offering was up against mine, I figured I had a chance. The fact that the model competing against my boxcar looked like a half-eaten Twinkie on toy train trucks, I will not comment on at this time. Cheers to the winner!

I noticed that my models where relegated to the darkest corners of the room, barely visible. The model which would eventually win, was outfitted in glaring spotlights, had its own special table, dead center in the room. Obvious? Humorously, it was a mediocre model that I noticed garnered many shakes of the head, not praise, and this assessment was deserved in my and Dennis’s opinion as well. It was certainly bright and gaudy!

But onward to utilizing the twenty bens I had in my pocket. We were all starting to have a pretty good time, walking around the huge vendor’s hall, looking at displays of running trains in various scales, riling up as many grumpy old men as we could, when—the inexplicable happened. Everything, and I mean everything shut down and closed at noon, and we were very rudely pushed out the doors into the blazing sunlight. Closed until 6:30 p. m. Now, that is one hell of a siesta period, even for those geezers.

Stunned, there was no choice but drive east in the Impala toward Rockland. Plan B was to visit the Dowling Walsh Gallery and show Dennis the painting for which he had traded his famous Sandy Harbor railroad pike. We motored smoothly along Route 17, opened a few beers dredged from the iced cooler, and felt the relief of being free from criminally depressed, nervous, narrow- (get it? narrow) gauge nuts and bolts.

Okay. Here comes the National treasure part. I know Maine has a few great diners left—Moody’s and Dysart’s being two. I won’t stall this column ranting on about what the perfect American diner used to be like and how they are either all gone or overly cute and precious. Why? Because I don’t have to, because one still exists that meets every possible criteria and hits the diner bull’s eye. The Come Spring Cafe in Union is one—old-school and “undiscovered.” It was so tasty, the waitress Brenda so charming and might I add cool in that ideal Maine way, that it all but brought tears to my eyes. Go there! Who knows how long it will last. The turkey Ruben is a sacrament. The haddock Ruben just as good. Everything homemade, of course. And that tomato basil soup? I’m headed for the Impala and the highway west now!

Dennis Brennan at the Come Spring Diner looking pretty darn sober. http://www.brennansmodelrr.com

Dennis liked his painting Midway in the original, we dipped at Lincolnville Beach where I’ve been swimming for only 57 years, and we beached the Impala back in Belfast once more. Always wonderful to be home although my agorophobia seemed less intrusive with Dennis around.

Morning, Friday, blazing hot temperatures, hang over into the red part of the gauge, back to the train meet to buy a few things before the bizarre noon closure of the vendor’s hall, and then head back home with my three models. Sounded pretty simple. But add that Freaking Bob—nothing is simple. Bob told me that if I removed my models before Saturday basically the Pope would curse me, I’ll be barred from heaven, stray dogs would bite my ankles and then pish on me once I’m down. What to do? Dennis and I consider our options. We decide to act like gentlemen, refusing to lower ourselves to these ill-mannered standards.

So . . . next day, Saturday, we drive the two hours yet again! We pick up my models, receive a few brutish comments from the drunken Greg, who claims to have smashed his fist into my gon. He thinks this is hilarious. Oddly, I’ve actually begun to like Greg quite a bit. I give him a $25 Time Diptych booklet from my second to last show, which he seems to admire (not easy to tell with him), and we head home.

Okay! I admit it. I’m crestfallen. I feel as if I’ve been shot with poisoned arrows. To have won nothing, NOTHING, really hurts. After all, I know my models are very good. You do not impress Lee Tuner with anything but the best. Hadn’t I won everything last time out?

Nothing to do but begin drinking again. At least I have Dennis, who is always cheerful, always ready for a drink. As a matter of fact, in one long week he didn’t turn down a single proffered beverage. I fling my name tag into the dry dead grass in front of the convention center and stamp off. OUCH!

The next morning, when I was asking Dennis how he could drink so much, he stared at me deadpan. I mean, I had never seen or even heard of anything like this guy (all 137 pounds of him), and I’ve been around a lot of alcoholics. Dennis looked at me, looked up at me, and said, “Well, you got to understand, I used have a drinking problem, you know.”

As an aside, I have exaggerated Dennis’s consumption a bit for comedic purposes, although yesterday on the way to the airport, all came clear. Dennis had stopped drinking. “I don’t want to arrive home drunk.” He looked just awful suddenly. “You, okay?” His face was paste, his normally sparkling green eyes basically closed from swelling. “I have a terrible headache, and an even worse stomachache,” he said, moaning a tad. “That’s called a hang over, Dennis.” “But I’m not vomiting continually.” “That’s called alcohol poisoning, Dennis.” “Oh. But I didn’t drink yesterday, did I?” Then we both really began to laugh.

As yet one more aside, I learned online from another modeler that I actually might have won something for my gondola. Bob probably stole my ribbon. Having seen his model—an untalented George Sellios on a mixture of meth and acid—I can understand why he needed my ribbon. Please enjoy, Bob!

The ladder that Dennis inadvertently stepped on after we returned from the contest.

The ladder after Dennis foot work.

Dennis painstakingly repairing said ladder that evening. He was up at dawn still adjusting rungs. Cheers to a great and legendary friend. No one rides shotgun quite like this man.

The disallowed document by Earle Mitchell:

THE STORY OF THE FAR NORTH PENOBSCOT CENTRAL TOWER:

William Gooding Mitchell was young, he was cocky and handsome, and he wasn’t going to listen to any of the idiots around him because he had had three months of university engineering after the war, so when he was hired to build a water tower, he wasn’t going to fail. He decided to multiply normal engineering practice by twelve. Why twelve? It was that much stronger than ten! And the roof would be banded in iron. No snow load was going to outsmart him and bring down his roof!

William Mitchell was chief engineer for the Penobscot Central Railroad as well as the Passagassawakeag River two footer line, both in Maine, both originating at Sandy Harbor. His new territory was the most northern spur to Eagle Lake, which had lost money every year since its inception. He would change all that. How? By building a water tower that signaled progress and affluence!

The Eagle Lake line went up the east branch of the Penobscot to a birch dowel mill at Nine Mile bridge on the Allagash. There were six switches along the way with flatcars on the sidings being loaded with fir and spruce pulpwood for the mills south on the river. It was a weekly run and lasted as long as it took to pick up the flatcars along the way. The harder the choppers cut wood the more cars to take out. They dropped off empties and shuffled fulls around until they had a full trainload out. It took more than a tender full of water to make the trip, so it was decided to put up a tank at Two Bears Spring about half way in. Before the tank, it had been swamp water, which, as William now knew, ruined a good boiler.

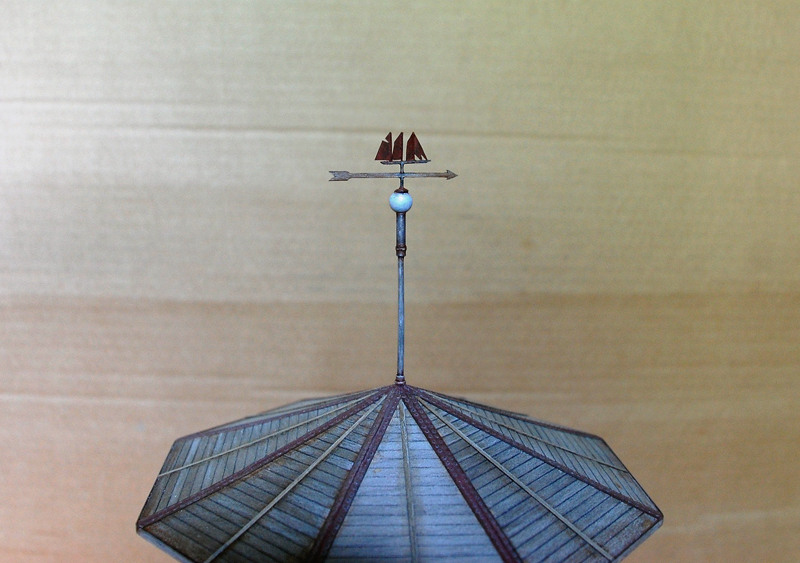

Caleb Reed was the stationmaster at Two Bears Spring if you could call it a station. It was a makeshift building that doubled as a station and freight shed with a cot for the master. Caleb Reed would crew for Mitchell on the run in as brakeman, fireman, whatever needed to be done—not too bright, he adored William. And then he would mind the water tank until the next run the following week. He had lots of time on his hands so he welded up a weathervane for the tank top. It was the three-masted schooner Dauntless on the vane, a memory from his long-past youth, and it swung smartly into the wind when it shifted, not that a railroad crew really needed the wind direction.

But both he and Mitchell were born on the coast near Sandy Harbor—a revered bond as far as Caleb was concerned—and knew the weather well and checked the direction of the wind every time they passed the water tank. Everything went smoothly most of the year—although William Mitchell was taken aback that no one seemed to notice the dignity and beauty of his tower, not to mention the size (largest on the line by far)—but along toward Thanksgiving it started getting colder and the water tank started to freeze up. This was a frigid part of Maine compared to the coast.

It froze from the outside in, so for some time, the tank gave enough water to keep the engine and the snow plow going. Along toward January it would freeze solid at around 30 below if you left it, so Caleb Reed placed an Atlantic end heater stove inside the frost locker under the tank. He would feed the coal or wood fire—whichever he had—all winter as the cold came and went, the ice would make and give and sooner or later, spring thaw would come and break the back of winter, and Caleb Reed could let his fires go for another year.

And all was good with Caleb and William.

One year a couple friends made the trip from Sandy in one pretty cold winter and stayed the week with Caleb. They brought some spirits with them, which Caleb didn’t know much about, but that went fast, so they started drinking the vanilla extract, but that didn’t last long. So they started straining sterno canned heat through bread, and that worked alright, except it was wood alcohol. One guy went blind and they almost lost another, and everyone was so drunk they left the lids off the stove and all but burned the frost locker down. They would have burned the tank if it wasn’t waterlogged and full of ice.

William was furious. His gorgeous tower, the symbol of his arrogant youth—which if truth be told had become a laughing stock as the line lost more and more revenue—was defiled. William fired Caleb, put in a waste gate to drain the tower each fall, and that seemed to be the end of it. Except Caleb, after becoming a terrible drunkard in Sandy Harbor, strayed back to his old haunts. He didn’t rebuild the frost locker, but they say you can still smell wood or coal smoke even on coldest January nights, even if there aren’t any train sounds or locomotive whistles.

Caleb’s Roost which was modeled inside the tower support structure. We even had Caleb standing there drinking a Narragansett. Oh, well . . . Maybe someday National modeling contests will include a category for model and story combined. What do you say, Bob?

True progress started pushing dirt roads in from Bangor and began moving wood on trucks and that drove the nails in the coffin for the Eagle Lake spur line. Seventy years later you can still walk the rail bed and get a nice surprise when you make the grade at Two Bears Spring. The old tank rotted years ago and fell in, but the iron roof trusses, spout, bands, chain and weights are still there along with the remains of the old stove, and topping it off is the old weathervane still turning into the wind forecasting the weather for anyone who might happen along.

Notes found recently (2016) written by either Caleb or maybe William or an unknown in a partially burnt journal:

“The old chain had to be abandoned because it only allowed the spout to raise so far before the counter weights bottomed out against the timber. A bush-fix was applied using newer pulleys and stout rope found at a ship yard which allowed the weights to clear the timber to raise the spout higher, for the taller smoke stack of the newer engine.”

“Bill Mitchell’s uncle Charles worked at Rigby Yard at Skowhegan Junction. He worked on the section crew, but he really was the blacksmith. He was the local wizard and had a reputation for being able to mend or make anything. His nephew was having troubles with the roof on the water tank. It had fallen in under a snow load the second time in three years. Uncle Charles forged up four v-trusses that fit to the tank top and bolted together at the peak. It was through bolted with clamps under the roofline and had a system of collarties and cable that kept it from pushing out the tank sides. Critics thought it was too heavy for the tank and would crush the roof by itself, but it was the last thing to go when the old tower fell.”

Slipped tank band and peeling paint. I figured out my own technique for weathering the wood and creating the peeling paint effect. Really easy! When you know how. So long 36th National Narrow Gauge Convention in Augusta, Maine 2016. You will never see my shadow again.

The schooner was made from paper and wire.

Dennis Brennan made everything but the water tower. It’s installed on the Sandy Harbor Penobscot Bay railroad on out third floor. We actually moved this model pike from Missouri to Maine. Truly an impossibility.

Amazing work as always, Eric. Both in your miniatures and story. Clearly those guys were hoaching with jealousy.

Thanks!

I agree! Great pieces of work, both literary and artistic. (Love the pot-bellied stove!)

Thank you, Jeanne. That comment means a lot as I respect your writing so much. Anyone reading this, please read Jeanne Schinto’s stories. Even John Updike thought she was amazing, and I certainly second his opinion.